Figure 1: Airmass measurements (clouds) over Ukraine from February 18, 2022 - March 01, 2022 from the SEVIRI instrument. Data accessed via the EUMETSAT Viewer.

Satellite imagery is a critical source of information during the current invasion of Ukraine. Military strategists, journalists, and researchers use this imagery to make decisions, unveil violations of international agreements, and inform the public of the stark realities of war. With Ukraine experiencing a large amount of cloud cover and attacks often occuring during night-time, many forms of satellite imagery are hindered from seeing the ground. Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) imagery penetrates cloud cover, but requires special training to interpret. Automating this tedious task would enable real-time insights, but current computer vision methods developed on typical RGB imagery do not properly account for the phenomenology of SAR. This leads to suboptimal performance on this critical modality. Improving the access to and availability of SAR-specific methods, codebases, datasets, and pretrained models will benefit intelligence agencies, researchers, and journalists alike during this critical time for Ukraine.

In this post, we present a baseline method and pretrained models that enable the interchangeable use of RGB and SAR for downstream classification, semantic segmentation, and change detection pipelines.

Introduction

We live in a rapidly changing world, one that experiences natural disasters, civic upheaval, war, and all sorts of chaotic events which leave unpredictable—and often permanent—marks on the face of the planet. Understanding this change has historically been difficult. Surveyors were sent out to explore our new reality, and their distributed findings were often noisily integrated into a source of reality. Maintaining a constant state of vigilance has been a goal of mankind since we were able to conceive such a thought, all the way from when Nadar took the first aerial photograph to when Sputnik 1’s radio signals were used to analyze the ionosphere.

Vigilance, or to the French, surveillance, has been a part of human history for millenia. As with any tool, it has been a double-edged sword. Historically, surveillance without checks and balances has been detrimental to society. Conversely, the proper and responsible surveillance has allowed us to learn deep truths about our world which have resulted in advances in the scientific and humanitarian domains. With the amount of satellites in orbit today, our understanding of the environment is updated almost daily. We have rapidly transitioned from having very little information to now having more data than we can meaningfully extract knowledge from. Storing this information, let alone understanding, is an engineering challenge that is of growing urgency.

Machine Learning and Remote Sensing

With hundreds of terabytes of data being downlinked from satellites to data centers every day, gaining knowledge and actionable insights from that data with manual processing has already become an impossible task. The most widely used form of remote sensing data is electro-optical (EO) satellite imagery. EO imagery is commonplace—anyone who has used Google Maps or similar mapping software has interacted with EO satellite imagery.

Machine learning (ML) on EO imagery is used in a wide variety of scientific and commercial applications. From improving precipitation predictions, analyzing human slavery by identifying brick kilns, to classifying entire cities to improve traffic routing, the outputs of ML on EO imagery have been integrated into almost every facet of human society.

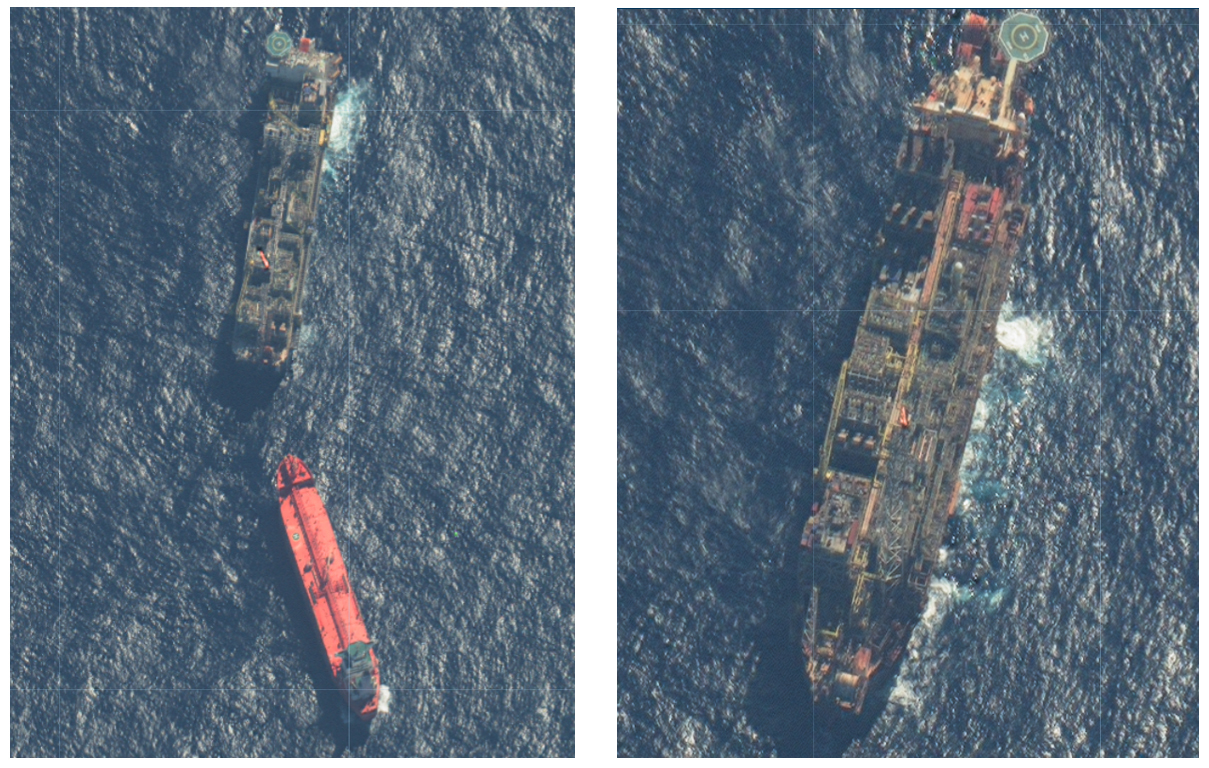

Figure 2: VHR EO imagery over the Kyiv region as acquired by Maxar on February 28, 2022.

Commonly used satellite constellations for EO imagery include the Landsat series of satellites operated by the United States Geological Survey and the Copernicus Sentinel-2 constellation operated by the European Space Agency. These constellations provide imagery at resolutions between 10-60 meters which is good enough for many use cases, but preclude the observation of finer details.

The Advent of Very High Resolution, Commercial Electro-Optical Satellite Imagery

Over the last few years, very high resolution (VHR) EO imagery has been made available through a variety of commercial sources. Ranging from between 0.3 - 2.0 meter resolution1, companies such as Planet, Maxar, Airbus, and others are providing extremely precise imagery with high revisit rates, imaging the entire planet every day.

The increased resolution provided by VHR imagery enables a litany of downstream use cases. Erosion can be detected at finer scales, and the building damage can be classified after natural disasters.

Machine learning methods have had to adapt in response to VHR satellite imagery. With an increased acuity, the amount of pixels and the amount of classes that can be discerned has increased by orders of magnitude. Computer vision research has responded by reducing the computational cost to learn efficient representation of satellite imagery, creating methods to alleviate the increased burden on labelers, and even engineering large software frameworks to allow computer vision practitioners to handle this abundant source of imagery.

In general, existing computer vision methods on other, non-aerial RGB imagery transfer very well to satellite imagery. This has allowed commercial VHR imagery to be immediately useful with highly accurate results.

The Problem with Electro-Optical Imagery

For highly turbulent and risky situations such as war and natural disasters, having constant, reliable access to the Earth is paramount. Unfortunately, EO imagery cannot solve all of our surveillance needs. EO can only detect light sources during daytime, and as it turns out, nearly 2/3rds of the Earth is covered by clouds at any given time. Unless you care about clouds, this blockage of the surface of the planet is problematic when understanding what happens on the ground is of critical importance. Machine learning methods attempt to sidestep this problem by predicting what the world would look like without clouds. However, the loss of information is fundamentally irrecoverable.

Synthetic Aperture Radar Imagery

Synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imagery is an active form of remote sensing in which a satellite transmits pulses of microwave radar waves down to the surface of the Earth. These radar waves reflect off the ground and any objects on it and are returned back to the satellite. By processing these pulses over time and space, a SAR image is formed where each pixel is the superposition of different radar scatters.

Radar waves penetrate clouds, and since the satellite is actively producing the radar waves, it illuminates the surface of the Earth even during the night. Synthetic aperture radar has a wide variety of uses, being used to estimate the roughness of the Earth, mapping the extent of flooding over large areas, and to detect the presence of illegal fishing vessels in protected waters.

There are multiple SAR satellite constellations in operation at the moment. The Copernicus Sentinel-1 constellation provides imagery to the public at large with resolutions ranging from 10 - 80 meters (10 meter imagery being the most common. Most commercial SAR providers, such as ICEYE and Capella Space, provide imagery down to 0.5 meter resolution. In upcoming launches, other commercial vendors aim to produce SAR imagery with sub-0.5 meter resolution with high revisit rates as satellite constellations grow and government regulations evolve.

Figure 4: A VHR SAR image provided by Capella Space over the Ukraine-Belarus border.

The Wacky World of Synthetic Aperture Radar Imagery

While SAR imagery, at a quick glance, may look very similar to EO imagery, the underlying physics is quite different, which leads to many interesting effects in the imagery product which can be counterintuitive and incompatible with modern computer vision. Three common effects are termed polarization, layover, and multi-path effects.

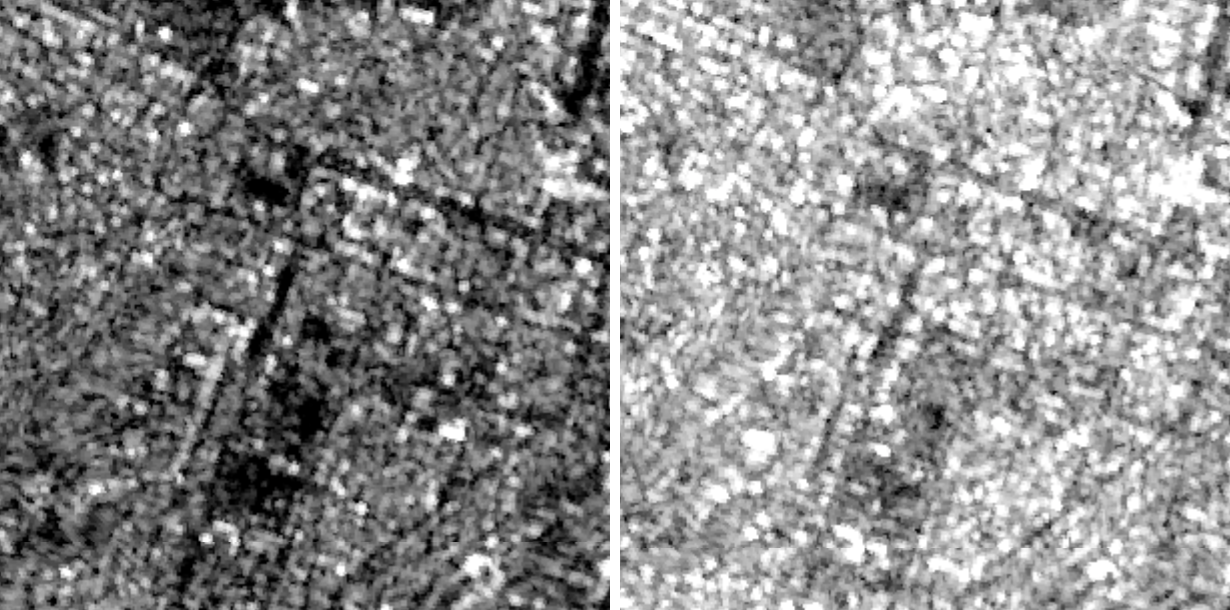

Radar antennas on SAR satellites often transmit polarized radar waves. The direction of polarization is the orientation of the wave’s electric field. Objects on the ground exhibit different responses to the different polarizations of radar waves. Therefore, SAR satellites often operate in dual or quad-polarization modes, broadcasting horizontally (H) or vertically (V) polarized waves and reading either polarization back, resulting in HH, HV, VH, and VV bands. You can contrast this with RGB bands in EO imagery, but the fundamental physics are different.

Figure 5: Difference between VH (left) and VV (right) polarizations over the same region in Dnipro, Ukraine from Sentinel-1 radiometric terrain corrected imagery. As seen here, the radar returns in corresponding local regions can be different.

Layover is an effect in which radar beams reach the top of a structure before they reach the bottom, resulting in the top of the object being presented as overlapping with the bottom. This happens when objects are particularly tall. Visually, tall buildings appear as if they are laying on their side, while mountains will have their peaks intersecting with their bases.

Figure 6: Example of layover in Capella’s VHR SAR imagery. The upper portion of the stadium is intersecting, seemingly, with the parking lot behind it.

Multi-path effects occur when radar waves reflect off of objects on the ground and incur multiple bounces before returning to the SAR sensor. Multi-path effects result in objects appearing in the imagery in various transformations in the resulting image. This effect can be seen everywhere in SAR imagery, but is particularly noticeable in urban areas, forests, and other dense environments.

Figure 7: Example of a multi-path effect on a bridge from oblique SAR imagery.

Existing computer vision methods that are built on traditional RGB imagery are not built with these effects in mind. Object detectors trained on EO satellite imagery assume that a unique object will only appear once, or that the object will appear relatively similar in different contexts, rather than potentially mirrored or scattered or interwoven with surrounding objects. The very nature of occlusion and the vision principles underlying the assumptions of occlusion in EO imagery do not transfer to SAR. Taken together, existing computer vision techniques can transfer to SAR imagery, but with reduced performance and a set of systematic errors that can be addressed through SAR-specific methodology.

Computer Vision on SAR Imagery for Ukraine

Imagery analysts are currently relying on both EO and SAR imagery where available over Ukraine. When EO imagery is available, existing computer vision tooling built for that modality is used to expedite the process of intelligence gathering. However, when only SAR imagery is available, these toolchains cannot be used. Imagery analysts have to resort to manual analysis which is time consuming and can be prone to mistakes. This topic is being explored by some other institutions internationally, however, it still remains an understudied area with respect to the amount of data available.

At Berkeley AI Research, we have created an initial set of methods and models that have learned robust representations for RGB, SAR, and co-registered RGB + SAR imagery from the publicly released BigEarthNet-MM dataset and the data from Capella’s Open Data, which consists of both RGB and SAR imagery. As such, using our models, imagery analysts are able to interchangeably use RGB, SAR, or co-registered RGB+SAR imagery for downstream tasks such as image classification, semantic segmentation, object detection, or change detection.

Given that SAR is a phenomenologically different data source than EO imagery, we have found that the Vision Transformer (ViT) is a particularly effective architecture for representation learning with SAR as it removes the scale and shift invariant inductive biases built into convolutional neural networks. Our top performing method, MAERS, for representation learning on RGB, SAR, and co-registered RGB + SAR builds upon the Masked Autoencoder (MAE) recently introduced by He et. al., where the network learns to encode the input data by taking a masked version of the data as input, encoding the data, and then learning to decode the data in such a way that it reconstructs the unmasked input data.

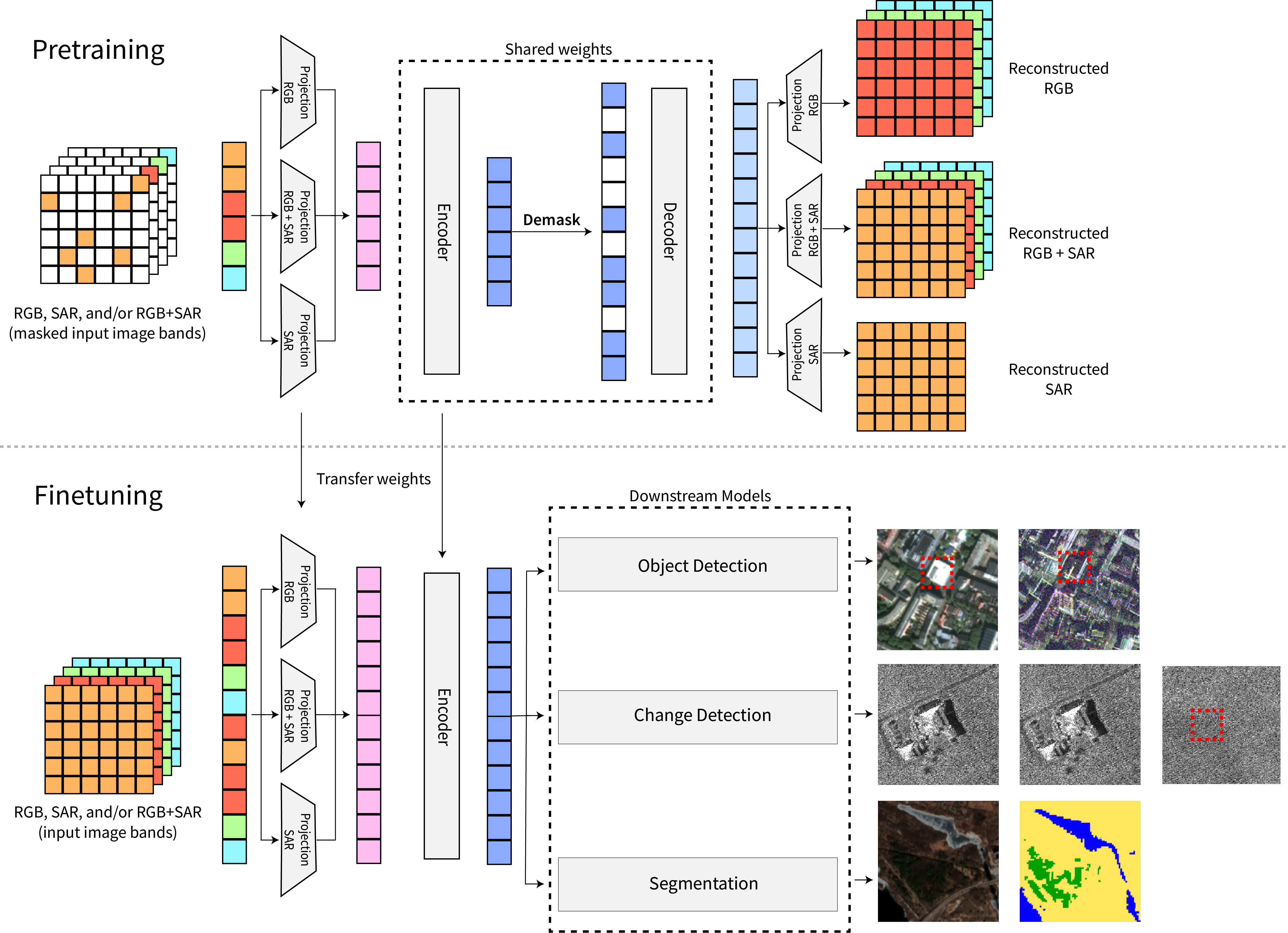

Contrary to popular classes of contrastive learning techniques, the MAE does not presuppose certain augmentation invariances in the data that may be incorrect for SAR features. Instead, it solely relies on reconstructing the original input, which is agnostic to RGB, SAR, or co-registered modalities. As shown in Figure 8, MAERS further extends MAE by learning independent input projection layers for RGB, SAR, and RGB+SAR channels, encoding the output of these projected layers using a shared ViT, and then decoding to the RGB, SAR, or RGB+SAR channels using independent output projection layers. The input projection layers and shared ViT can then be transferred to downstream tasks, such as object detection or change detection, where the input encoder can then take RGB, SAR, or RGB+SAR as input.

Figure 8: (top) A visualization of MAERS to learn a joint representation and encoder that can be used for a (bottom) downstream task, such as object detection on either, or both, modalities.

Learning representations for RGB, SAR, and co-registered modalities can benefit a range of downstream tasks, such as content-based image retrieval, classification, segmentation, and detection. To demonstrate the effectiveness of our learned representations, we perform experiments on the well-established benchmarks of 1) multi-label classification of co-registered EO and SAR scenes from the BigEarthNet-MM dataset, and 2) semantic segmentation on the VHR EO and SAR SpaceNet 6 dataset.

Multi-Label Classification on BigEarth-MM

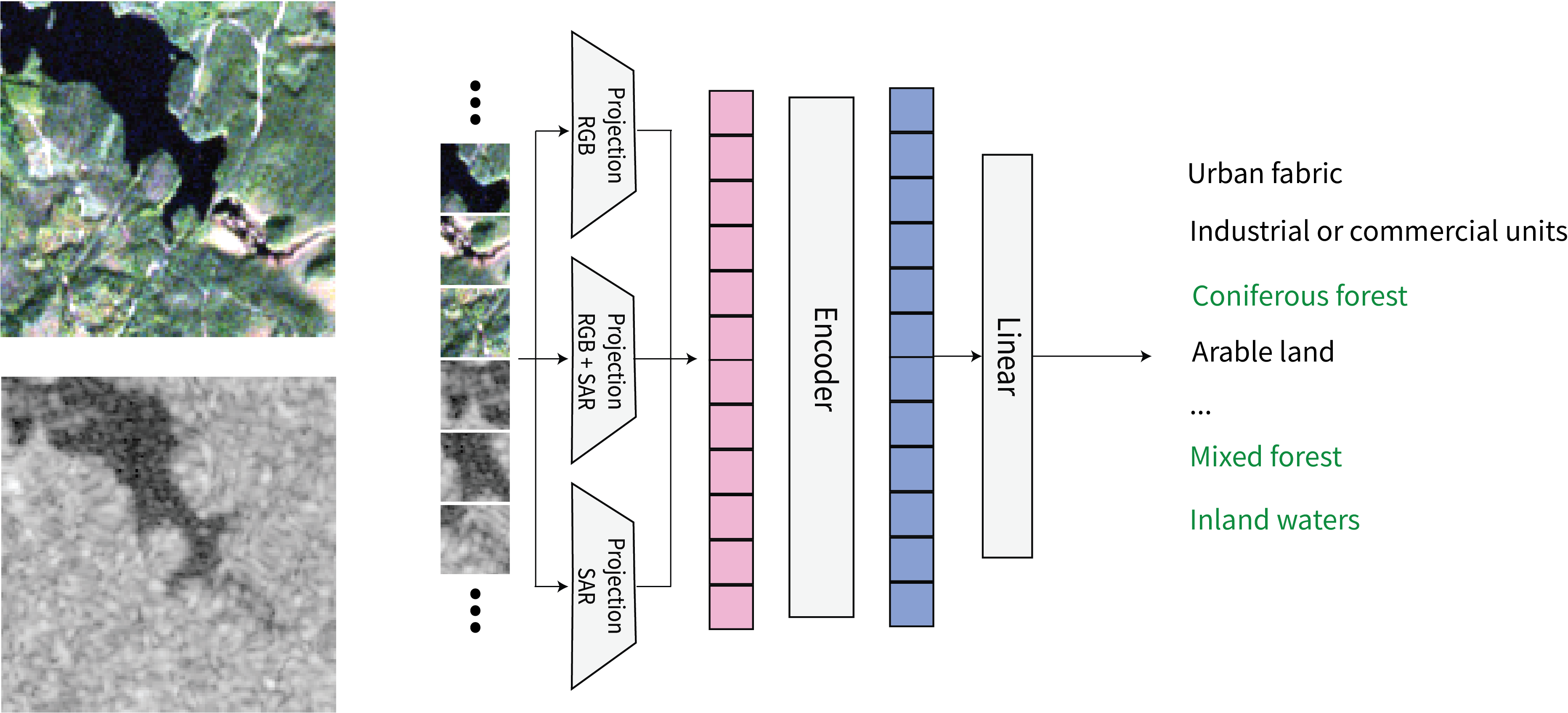

Figure 9: (left) co-registered Sentinel-2 EO and Sentinel-1 SAR imagery are patchified and used to perform a multi-label classification task as specified by the BigEarth-MM challenge. A linear layer is added to our multi-modal encoder and then fine-tuned end-to-end.

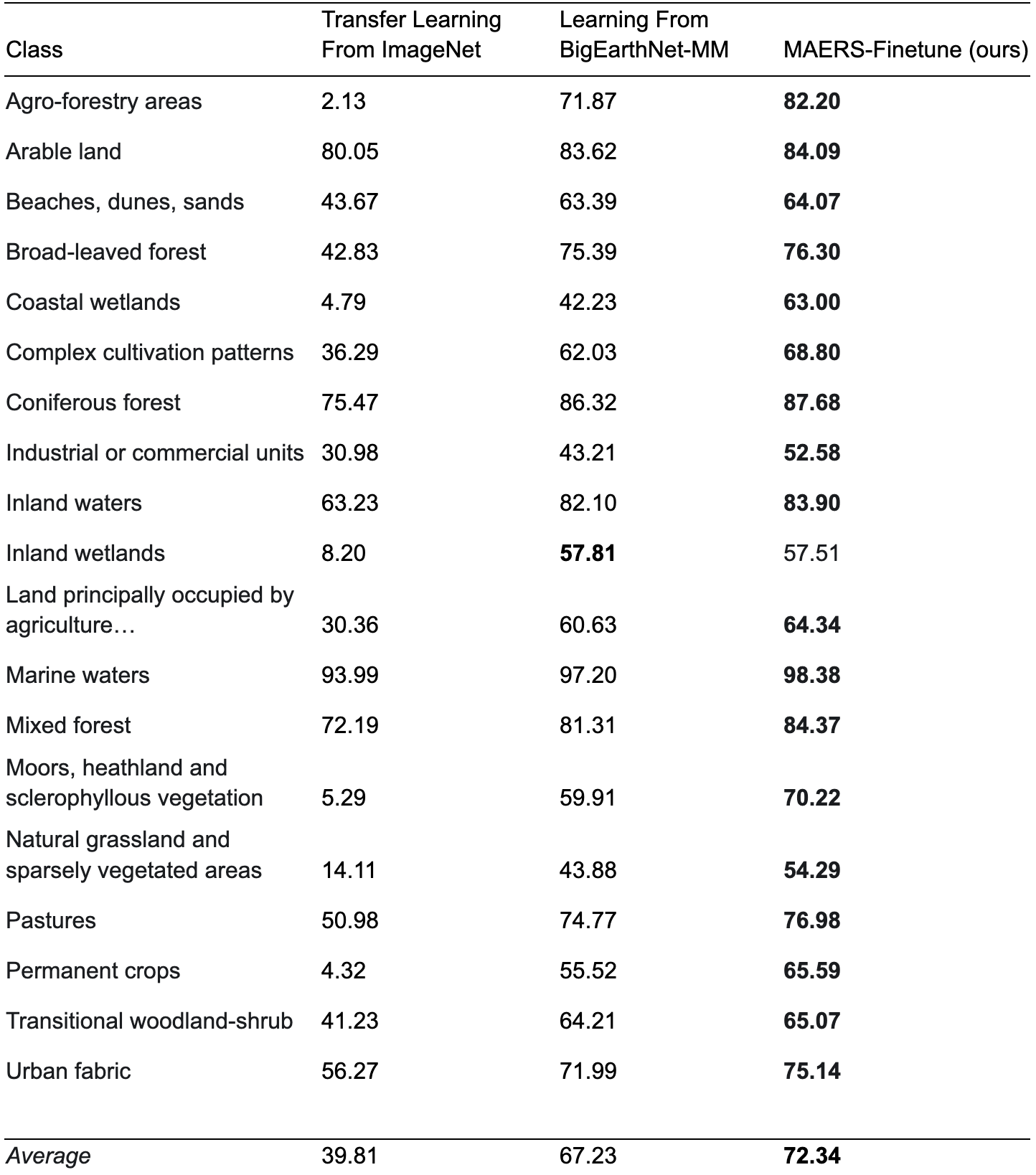

MAERS is initialized with a set of ImageNet weights for a ViT-Base encoder, followed by pretraining on the BigEarthNet-MM dataset for 20 epochs with RGB, SAR, and RGB+SAR imagery. We append a single linear layer to the MAERS encoder and learn the multi-label classification task by fine-tuning the entire model for 20 epochs (linear probing experiments obtain similar results, as we will show in our upcoming paper). Our results are shown in Table 1. MAERS with fine-tuning outperforms the best RGB+SAR results as presented in the BigEarthNet-MM paper, and show that adapting the State-of-the-Art MAE architecture for representation learning for RGB, SAR, and RGB+SAR input modalities leads to State-of-the-Art results.

Table 1: Reported per-class F2 scores on the test set of BigEarthNet-MM.

Semantic Segmentation on VHR EO and SAR SpaceNet 6

We further experimented with transfer learning for a timely task that will aid imagery analysts aiming to understand the destruction in Ukraine: semantic segmentation of buildings footprints, which is a precursor task to performing building damage assessment. Building damage assessment is of direct interest to government officials, journalists, and human rights organizations aiming to understand the scope and severity of Russia’s attacks against infrastructure and civilian populations.

Figure 10: Example of building SAR-based MAERS segmentation taken from SpaceNet6, where the image on the left shows the RGB image, and the image on the right shows the SAR image with overlaid segmentation results. The SAR image is displayed in false color with VV, VH, and VV/VH bands.

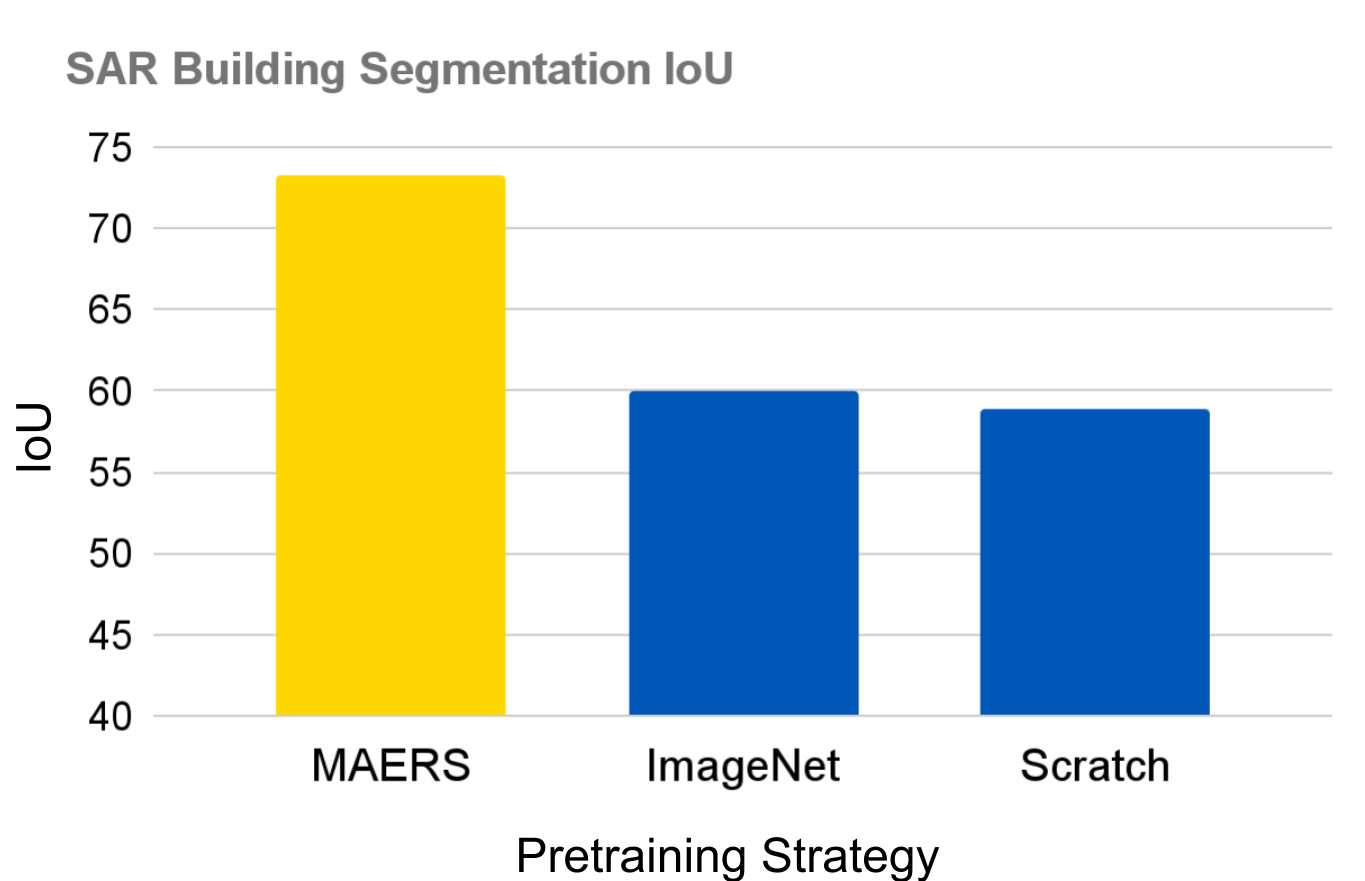

For this experiment, we used the SpaceNet 6 dataset as an open and public benchmark to illustrate the effectiveness of our learned representations for building footprint detection with VHR SAR from Capella Space. We used this encoder in tandem with the UperNet architecture for semantic segmentation. Figure 11 shows the IoU performance of segmenting building footprints in a held-out validation component of the SpaceNet 6 with only SAR input imagery, on a segmentation model that was trained to use either SAR or RGB imagery. The MAERS pretrained model leads to a ~13 point improvement compared to training the RGB+SAR model from scratch or adapting ImageNet weights with the exact same architecture.

This demonstrates that MAERS can learn robust RGB+SAR representations that allow a practitioner to use EO or SAR imagery interchangeably to accomplish downstream tasks. It is important to note that the phenomenology of SAR imagery is not fully conducive for building segmentation and that using EO imagery for this task leads to IoU scores > 90. This leaves a substantial gap yet to be covered by SAR techniques, something we hope to cover in our following paper. However, getting this performance out of SAR is essential when environmental conditions are not conducive to EO imagery capture.

Figure 11: Building segmentation IoU on the SpaceNet 6 Challenge, using an UperNet segmentation model with a ViT backbone. MAERS pretraining leads to ~13 point gain in IoU performance compared to training from scratch or adapting ImageNet pretrained weights.

These results are preliminary, but compelling. We will follow up this effort with a publication with a detailed set of experiments and benchmarks. Furthermore, we will aid in the transition of our models to our humanitarian partners to enable them to perform change detection over residential and other civilian areas to enable better tracking of war crimes being committed in Ukraine.

These models are created with the goal of increasing the efficacy of organizations involved in humanitarian missions that are keeping a watchful eye on the war in Ukraine. However, as with any technology, it is our responsibility to understand how this technology could be misused. Therefore, we have designed these models with input from partners who perform intelligence and imagery analysis in humanitarian settings. By taking into account their thoughts, comments, and critiques, we are releasing a capability we are confident will be used for the good of humanity and with processes which dictate their safe and responsible use.

Call to Action

As citizens of free democracies who develop technologies which help us make sense of the complicated, chaotic, and counter-intuitive world that we live in, we have a responsibility to act when acts of injustice occur. Our colleagues and friends in Ukraine are facing extreme uncertainties and danger. We possess skills in the cyber domain that can aid in the fight against Russian forces. By focusing our time and efforts, whether that be through targeted research or volunteering our time in helping keep track of processing times at border crossings, we can make a small dent in an otherwise difficult situation.

We urge our fellow computer scientists to partner with government and humanitarian organizations and listen to their needs as difficult times persist. Simple things can make large differences.

Model and Weights

The models are not being made publicly accessible at this time. We are releasing our models to qualified researchers and partners through this form. Full distribution will follow once we have completed a thorough assessment of our models.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Gen. Steve Butow and Dr. Nirav Patel at the Department of Defense’s Defense Innovation Unit for reviewing this post and providing their expertise on the future of commercial SAR constellations.

Footnotes

-

It’s interesting to note that the definition of VHR imagery has changed over time. In the 80s, 20 kilometer resolution was “VHR”. Perhaps, in the future, 0.3m resolution imagery will no longer be VHR. ↩