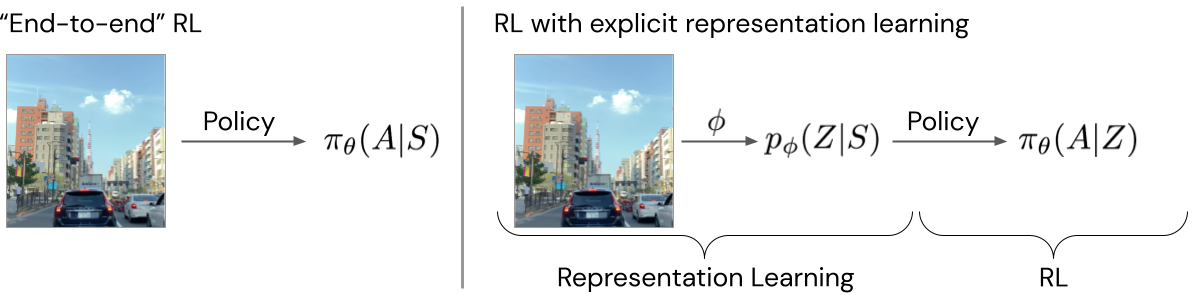

Processing raw sensory inputs is crucial for applying deep RL algorithms to real-world problems. For example, autonomous vehicles must make decisions about how to drive safely given information flowing from cameras, radar, and microphones about the conditions of the road, traffic signals, and other cars and pedestrians. However, direct “end-to-end” RL that maps sensor data to actions (Figure 1, left) can be very difficult because the inputs are high-dimensional, noisy, and contain redundant information. Instead, the challenge is often broken down into two problems (Figure 1, right): (1) extract a representation of the sensory inputs that retains only the relevant information, and (2) perform RL with these representations of the inputs as the system state.

Figure 1. Representation learning can extract compact representations of states for RL.

A wide variety of algorithms have been proposed to learn lossy state representations in an unsupervised fashion (see this recent tutorial for an overview). Recently, contrastive learning methods have proven effective on RL benchmarks such as Atari and DMControl (Oord et al. 2018, Stooke et al. 2020, Schwarzer et al. 2021), as well as for real-world robotic learning (Zhan et al.). While we could ask which objectives are better in which circumstances, there is an even more basic question at hand: are the representations learned via these methods guaranteed to be sufficient for control? In other words, do they suffice to learn the optimal policy, or might they discard some important information, making it impossible to solve the control problem? For example, in the self-driving car scenario, if the representation discards the state of stoplights, the vehicle would be unable to drive safely. Surprisingly, we find that some widely used objectives are not sufficient, and in fact do discard information that may be needed for downstream tasks.

Defining the Sufficiency of a State Representation

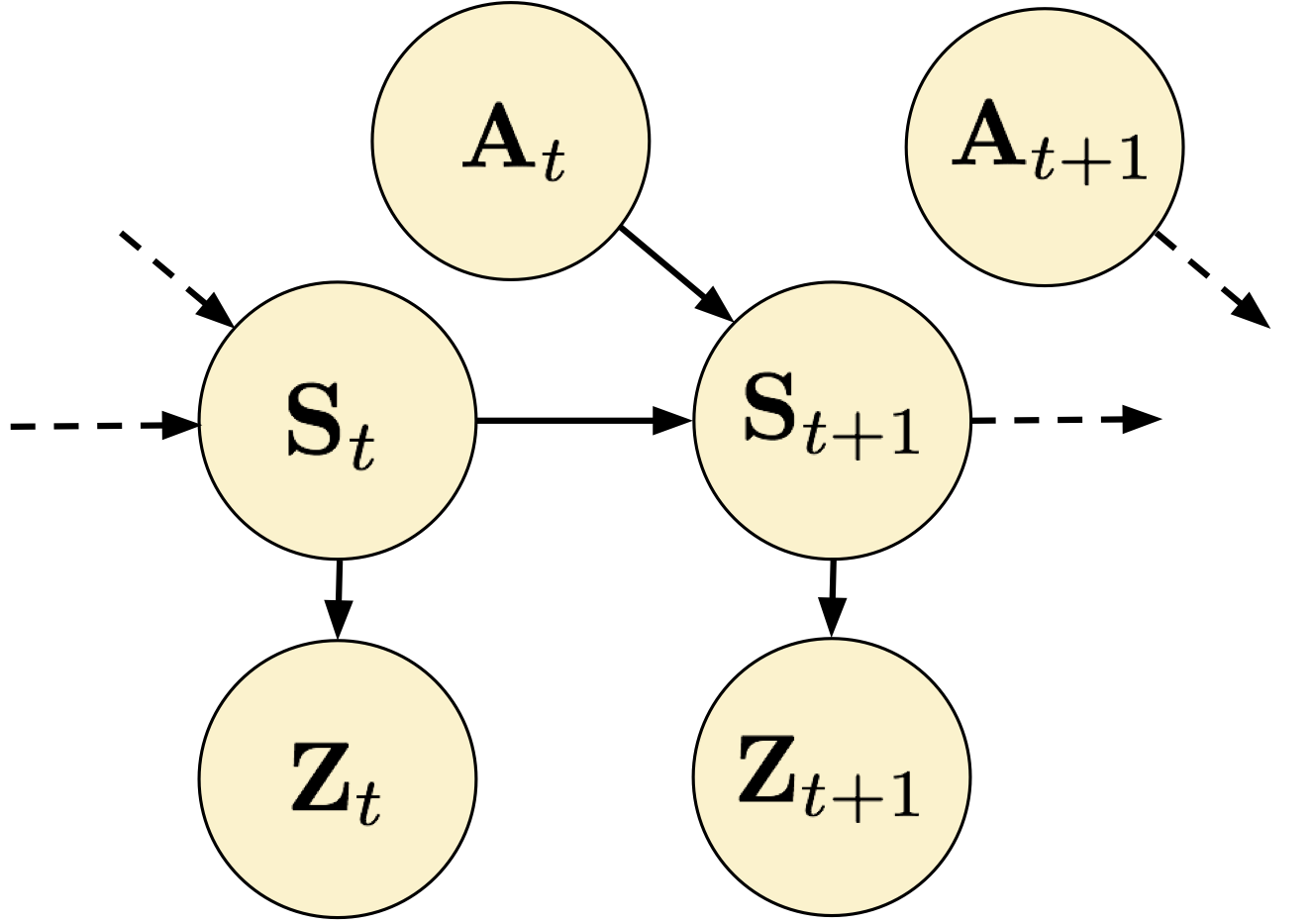

As introduced above, a state representation is a function of the raw sensory inputs that discards irrelevant and redundant information. Formally, we define a state representation $\phi_Z$ as a stochastic mapping from the original state space $\mathcal{S}$ (the raw inputs from all the car’s sensors) to a representation space $\mathcal{Z}$: $p(Z | S=s)$. In our analysis, we assume that the original state $\mathcal{S}$ is Markovian, so each state representation is a function of only the current state. We depict the representation learning problem as a graphical model in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The representation learning problem in RL as a graphical model.

We will say that a representation is sufficient if it is guaranteed that an RL algorithm using that representation can learn the optimal policy. We make use of a result from Li et al. 2006, which proves that if a state representation is capable of representing the optimal $Q$-function, then $Q$-learning run with that representation as input is guaranteed to converge to the same solution as in the original MDP (if you’re interested, see Theorem 4 in that paper). So to test if a representation is sufficient, we can check if it is able to represent the optimal $Q$-function. Since we assume we don’t have access to a task reward during representation learning, to call a representation sufficient we require that it can represent the optimal $Q$-functions for all possible reward functions in the given MDP.

Analyzing Representations learned via MI Maximization

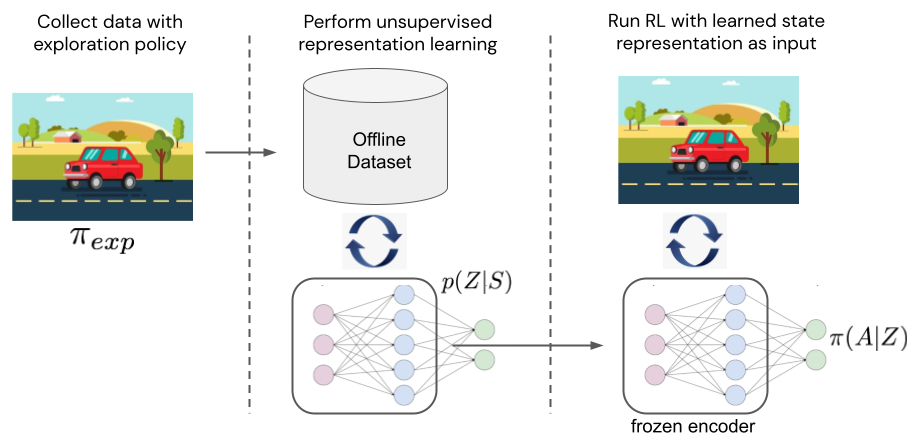

Now that we’ve established how we will evaluate representations, let’s turn to the methods of learning them. As mentioned above, we aim to study the popular class of contrastive learning methods. These methods can largely be understood as maximizing a mutual information (MI) objective involving states and actions. To simplify the analysis, we analyze representation learning in isolation from the other aspects of RL by assuming the existence of an offline dataset on which to perform representation learning. This paradigm of offline representation learning followed by online RL is becoming increasingly popular, particularly in applications such as robotics where collecting data is onerous (Zhan et al. 2020, Kipf et al. 2020). Our question is therefore whether the objective is sufficient on its own, not as an auxiliary objective for RL. We assume the dataset has full support on the state space, which can be guaranteed by an epsilon-greedy exploration policy, for example. An objective may have more than one maximizing representation, so we call a representation learning objective sufficient if all the representations that maximize that objective are sufficient. We will analyze three representative objectives from the literature in terms of sufficiency.

Representations Learned by Maximizing “Forward Information”

We begin with an objective that seems likely to retain a great deal of state information in the representation. It is closely related to learning a forward dynamics model in latent representation space, and to methods proposed in prior works (Nachum et al. 2018, Shu et al. 2020, Schwarzer et al. 2021): $J_{fwd} = I(Z_{t+1}; Z_t, A_t)$. Intuitively, this objective seeks a representation in which the current state and action are maximally informative of the representation of the next state. Therefore, everything predictable in the original state $\mathcal{S}$ should be preserved in $\mathcal{Z}$, since this would maximize the MI. Formalizing this intuition, we are able to prove that all representations learned via this objective are guaranteed to be sufficient (see the proof of Proposition 1 in the paper).

While reassuring that $J_{fwd}$ is sufficient, it’s worth noting that any state information that is temporally correlated will be retained in representations learned via this objective, no matter how irrelevant to the task. For example, in the driving scenario, objects in the agent’s field of vision that are not on the road or sidewalk would all be represented, even though they are irrelevant to driving. Is there another objective that can learn sufficient but lossier representations?

Representations Learned by Maximizing “Inverse Information”

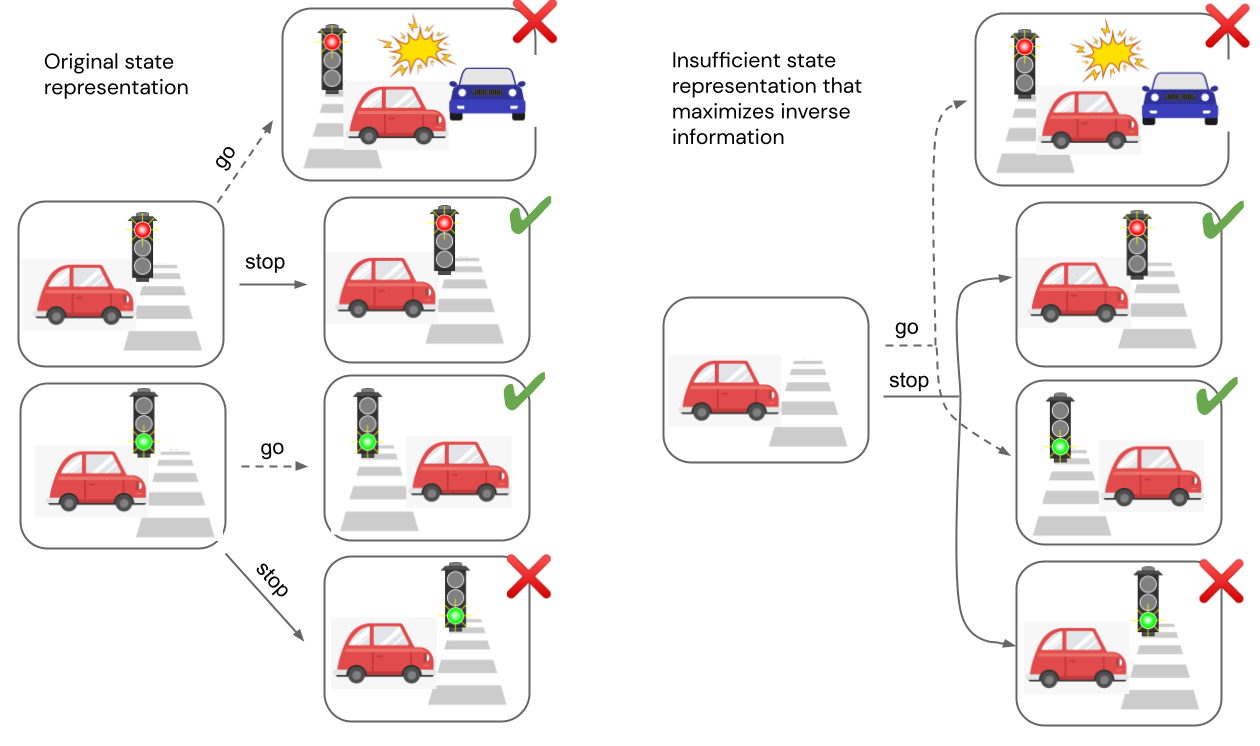

Next, we consider what we term an “inverse information” objective: $J_{inv} = I(Z_{t+k}; A_t | Z_t)$. One way to maximize this objective is by learning an inverse dynamics model – predicting the action given the current and next state – and many prior works have employed a version of this objective (Agrawal et al. 2016, Gregor et al. 2016, Zhang et al. 2018 to name a few). Intuitively, this objective is appealing because it preserves all the state information that the agent can influence with its actions. It therefore may seem like a good candidate for a sufficient objective that discards more information than $J_{fwd}$. However, we can actually construct a realistic scenario in which a representation that maximizes this objective is not sufficient.

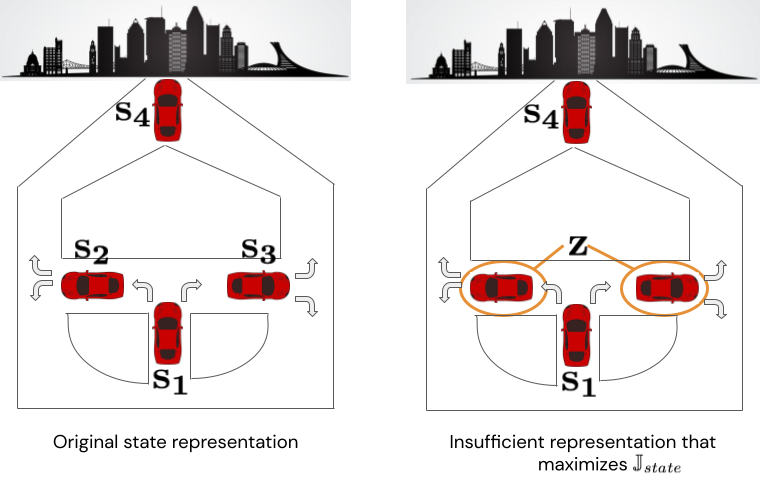

For example, consider the MDP shown on the left side of Figure 4 in which an autonomous vehicle is approaching a traffic light. The agent has two actions available, stop or go. The reward for following traffic rules depends on the color of the stoplight, and is denoted by a red X (low reward) and green check mark (high reward). On the right side of the figure, we show a state representation in which the color of the stoplight is not represented in the two states on the left; they are aliased and represented as a single state. This representation is not sufficient, since from the aliased state it is not clear whether the agent should “stop” or “go” to receive the reward. However, $J_{inv}$ is maximized because the action taken is still exactly predictable given each pair of states. In other words, the agent has no control over the stoplight, so representing it does not increase MI. Since $J_{inv}$ is maximized by this insufficient representation, we can conclude that the objective is not sufficient.

Figure 4. Counterexample proving the insufficiency of $J_{inv}$.

Since the reward depends on the stoplight, perhaps we can remedy the issue by additionally requiring the representation to be capable of predicting the immediate reward at each state. However, this is still not enough to guarantee sufficiency - the representation on the right side of Figure 4 is still a counterexample since the aliased states have the same reward. The crux of the problem is that representing the action that connects two states is not enough to be able to choose the best action. Still, while $J_{inv}$ is insufficient in the general case, it would be revealing to characterize the set of MDPs for which $J_{inv}$ can be proven to be sufficient. We see this as an interesting future direction.

Representations Learned by Maximizing “State Information”

The final objective we consider resembles $J_{fwd}$ but omits the action: $J_{state} = I(Z_t; Z_{t+1})$ (see Oord et al. 2018, Anand et al. 2019, Stooke et al. 2020). Does omitting the action from the MI objective impact its sufficiency? It turns out the answer is yes. The intuition is that maximizing this objective can yield insufficient representations that alias states whose transition distributions differ only with respect to the action. For example, consider a scenario of a car navigating to a city, depicted below in Figure 5. There are four states from which the car can take actions “turn right” or “turn left.” The optimal policy takes first a left turn, then a right turn, or vice versa. Now consider the state representation shown on the right that aliases $s_2$ and $s_3$ into a single state we’ll call $z$. If we assume the policy distribution is uniform over left and right turns (a reasonable scenario for a driving dataset collected with an exploration policy), then this representation maximizes $J_{state}$. However, it can’t represent the optimal policy because the agent doesn’t know whether to go right or left from $z$.

Figure 5. Counterexample proving the insufficiency of $J_{state}$.

Can Sufficiency Matter in Deep RL?

To understand whether the sufficiency of state representations can matter in practice, we perform simple proof-of-concept experiments with deep RL agents and image observations. To separate representation learning from RL, we first optimize each representation learning objective on a dataset of offline data, (similar to the protocol in Stooke et al. 2020). We collect the fixed datasets using a random policy, which is sufficient to cover the state space in our environments. We then freeze the weights of the state encoder learned in the first phase and train RL agents with the representation as state input (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Experimental setup for evaluating learned representations.

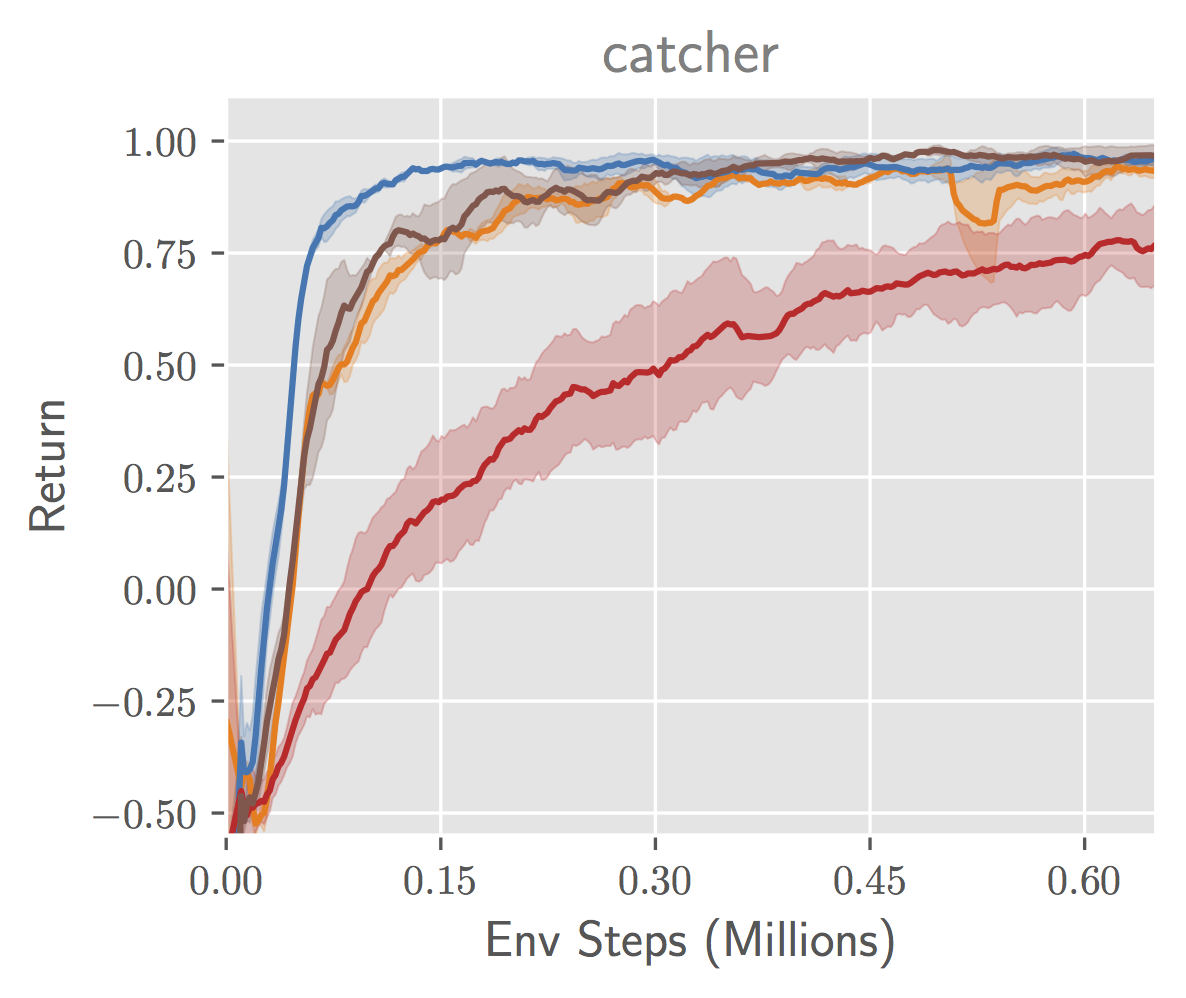

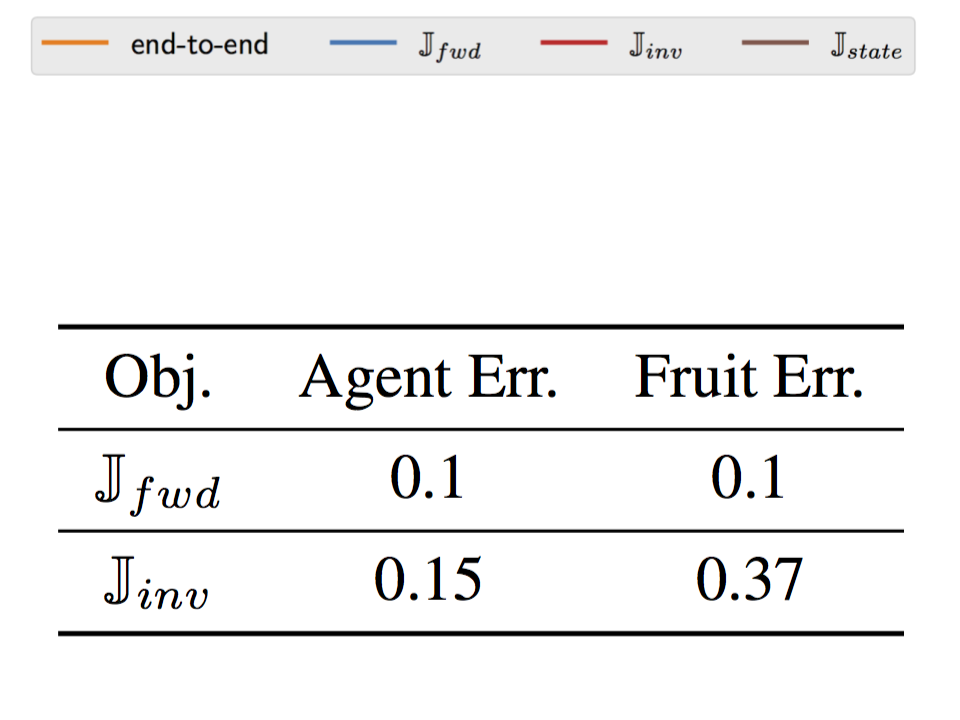

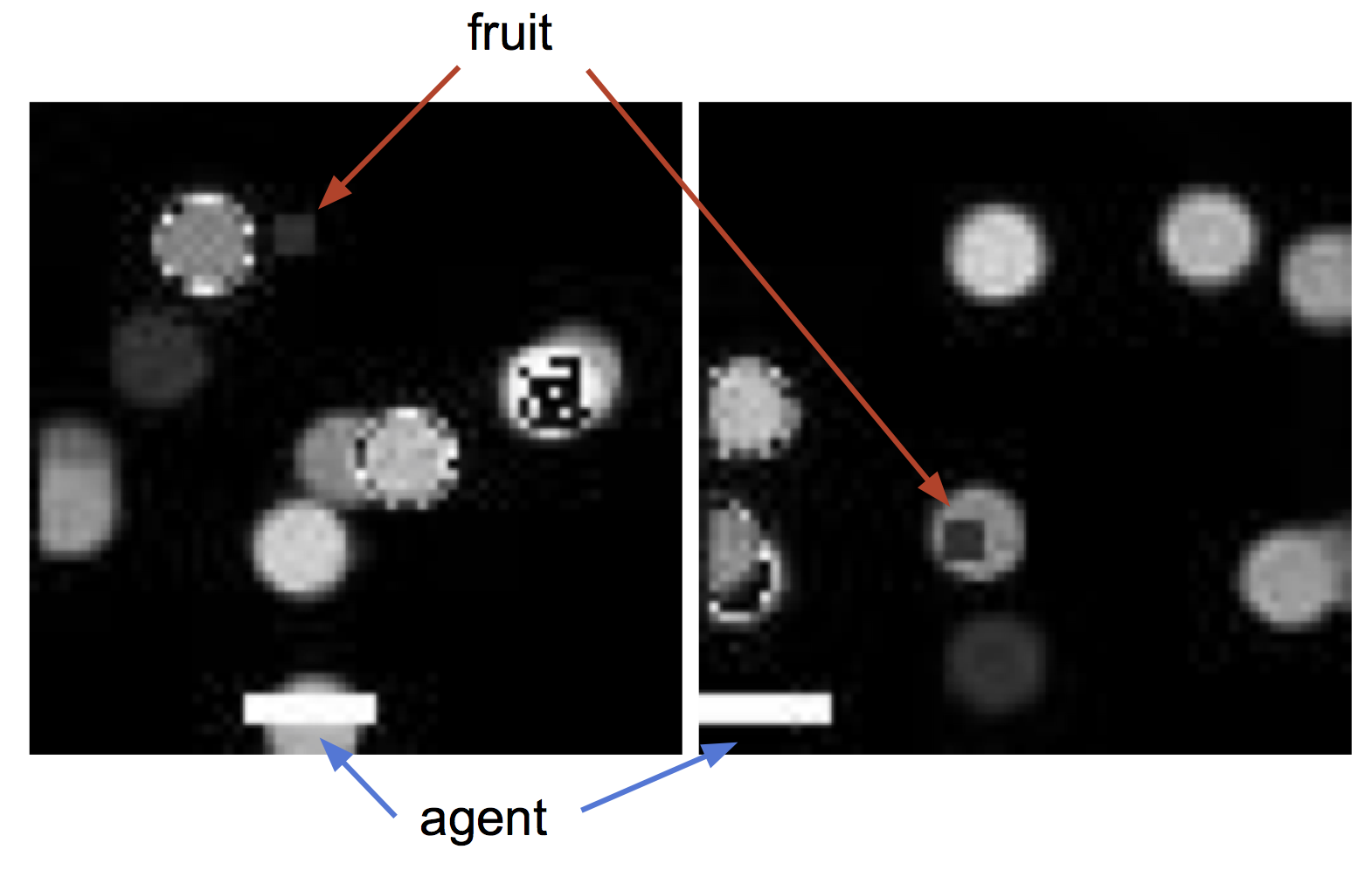

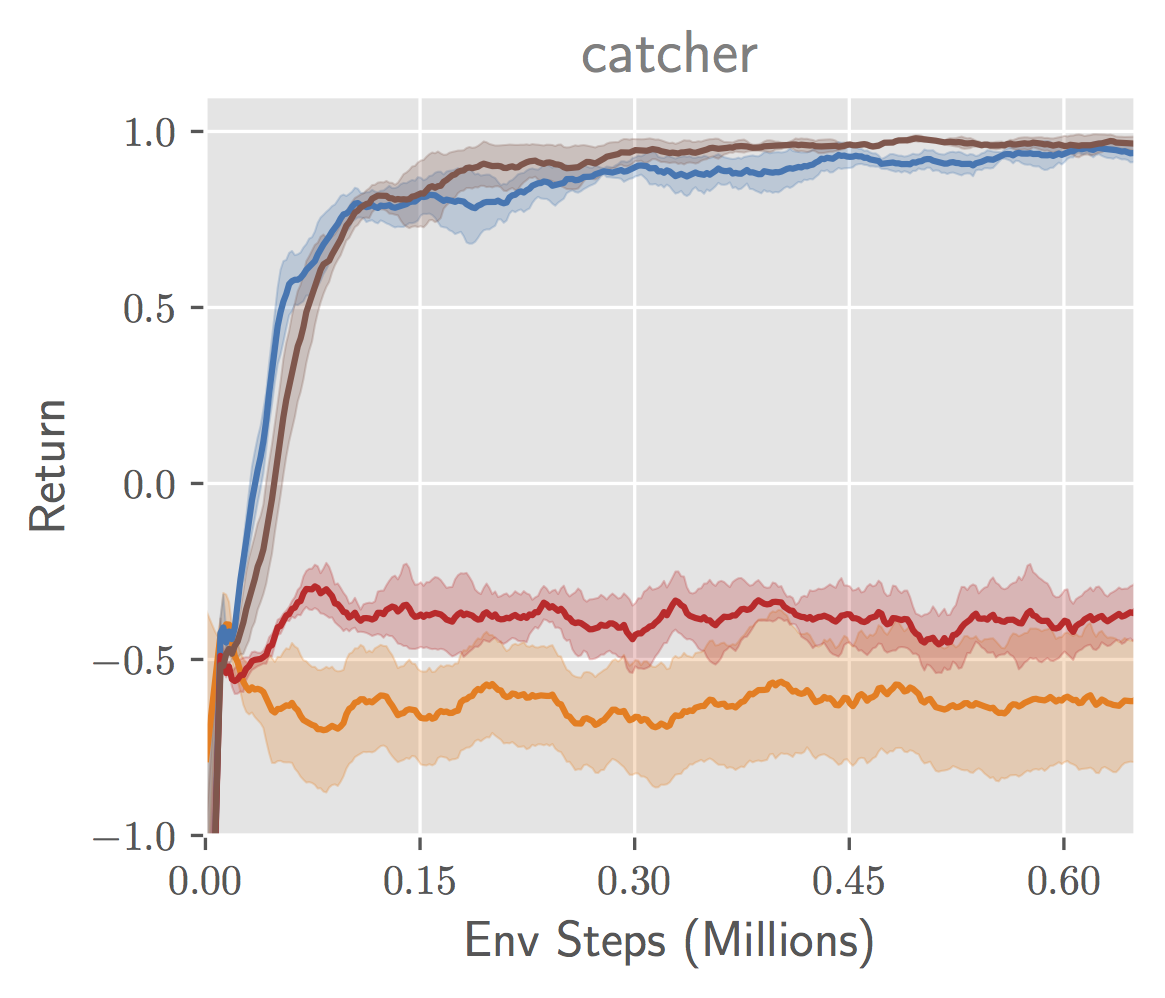

We experiment with a simple video game MDP that has a similar characteristic to the self-driving car example described earlier. In this game called catcher, from the PyGame suite, the agent controls a paddle that it can move back and forth to catch fruit that falls from the top of the screen (see Figure 7). A positive reward is given when the fruit is caught and a negative reward when the fruit is not caught. The episode terminates after one piece of fruit falls. Analogous to the self-driving example, the agent does not control the position of the fruit, and so a representation that maximizes $J_{inv}$ might discard that information. However, representing the fruit is crucial to obtaining reward, since the agent must move the paddle underneath the fruit to catch it. We learn representations with $J_{inv}$ and $J_{fwd}$, optimizing $J_{fwd}$ with noise contrastive estimation (NCE), and $J_{inv}$ by training an inverse model via maximum likelihood. (For brevity, we omit experiments with $J_{state}$ in this post – please see the paper!) To select the most compressed representation from among those that maximize each objective, we apply an information bottleneck of the form $\min I(Z; S)$. We also compare to running RL from scratch with the image inputs, which we call ``end-to-end.” For the RL algorithm, we use the Soft Actor-Critic algorithm.

Figure 7. (left) Depiction of the catcher game. (middle) Performance of RL agents trained with different state representations. (right) Accuracy of reconstructing ground truth state elements from learned representations.

We observe in Figure 7 (middle) that indeed the representation trained to maximize $J_{inv}$ results in RL agents that converge slower and to a lower asymptotic expected return. To better understand what information the representation contains, we then attempt to learn a neural network decoder from the learned representation to the position of the falling fruit. We report the mean error achieved by each representation in Figure 7 (right). The representation learned by $J_{inv}$ incurs a high error, indicating that the fruit is not precisely captured by the representation, while the representation learned by $J_{fwd}$ incurs low error.

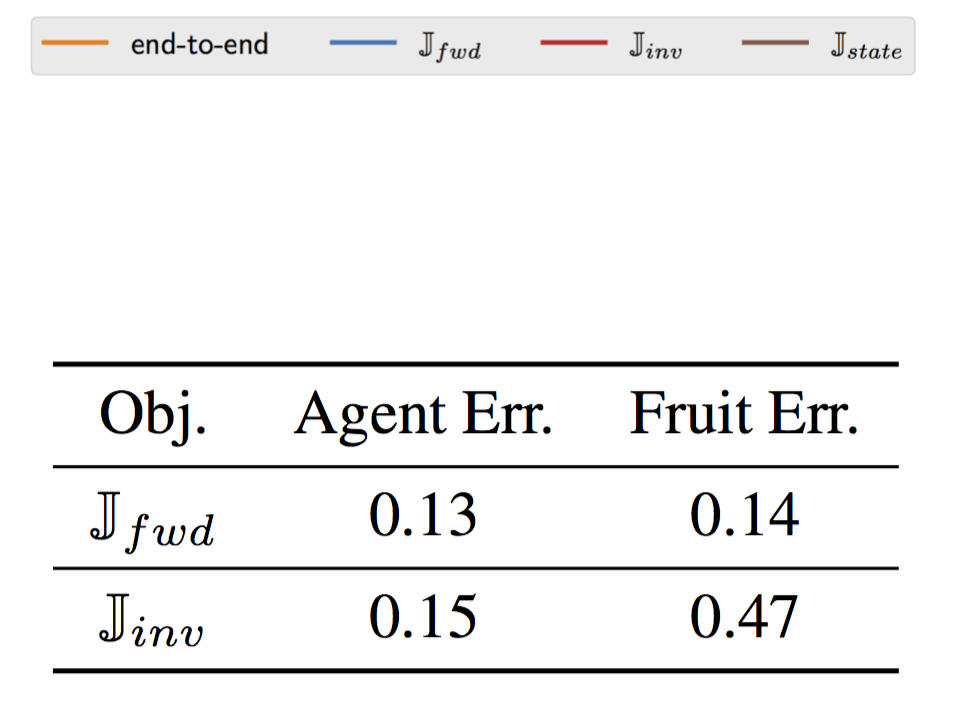

Increasing observation complexity with visual distractors

To make the representation learning problem more challenging, we repeat this experiment with visual distractors added to the agent’s observations. We randomly generate images of 10 circles of different colors and replace the background of the game with these images (see Figure 8, left, for example observations). As in the previous experiment, we plot the performance of an RL agent trained with the frozen representation as input (Figure 8, middle), as well as the error of decoding true state elements from the representation (Figure 8, right). The difference in performance between sufficient ($J_{fwd}$) and insufficient ($J_{inv}$) objectives is even more pronounced in this setting than in the plain background setting. With more information present in the observation in the form of the distractors, insufficient objectives that do not optimize for representing all the required state information may be “distracted” by representing the background objects instead, resulting in low performance. In this more challenging case, end-to-end RL from images fails to make any progress on the task, demonstrating the difficulty of end-to-end RL.

Figure 8. (left) Example agent observations with distractors. (middle) Performance of RL agents trained with different state representations. (right) Accuracy of reconstructing ground truth state elements from state representations.

Conclusion

These results highlight an important open problem: how can we design representation learning objectives that yield representations that are both as lossy as possible and still sufficient for the tasks at hand? Without further assumptions on the MDP structure or knowledge of the reward function, is it possible to design an objective that yields sufficient representations that are lossier than those learned by $J_{fwd}$? Can we characterize the set of MDPs for which insufficient objectives $J_{inv}$ and $J_{state}$ would be sufficient? Further, extending the proposed framework to partially observed problems would be more reflective of realistic applications. In this setting, analyzing generative models such as VAEs in terms of sufficiency is an interesting problem. Prior work has shown that maximizing the ELBO alone cannot control the content of the learned representation (e.g., Alemi et al. 2018). We conjecture that the zero-distortion maximizer of the ELBO would be sufficient, while other solutions need not be. Overall, we hope that our proposed framework can drive research in designing better algorithms for unsupervised representation learning for RL.

This post is based on the paper Which Mutual Information Representation Learning Objectives are Sufficient for Control?, to be presented at Neurips 2021. Thank you to Sergey Levine and Abhishek Gupta for their valuable feedback on this blog post.