Fig. 1: The BRIDGE dataset contains 7200 demonstrations of kitchen-themed manipulation tasks across 71 tasks in 10 domains. Note that any GIF compression artifacts in this animation are not present in the dataset itself.

When we apply robot learning methods to real-world systems, we must usually collect new datasets for every task, every robot, and every environment. This is not only costly and time-consuming, but it also limits the size of the datasets that we can use, and this, in turn, limits generalization: if we train a robot to clean one plate in one kitchen, it is unlikely to succeed at cleaning any plate in any kitchen. In other fields, such as computer vision (e.g., ImageNet) and natural language processing (e.g., BERT), the standard approach to generalization is to utilize large, diverse datasets, which are collected once and then reused repeatedly. Since the dataset is reused for many models, tasks, and domains, the up-front cost of collecting such large reusable datasets is worth the benefits. Thus, to obtain truly generalizable robotic behaviors, we may need large and diverse datasets, and the only way to make this practical is to reuse data across many different tasks, environments, and labs (i.e. different background lighting conditions, etc.).

Each end-user of such a dataset might want their robot to learn a different task, which would be situated in a different domain (e.g., a different laboratory, home, etc.). Therefore, any reusable dataset would need to cover a sufficient variety of tasks and environments to allow the learning algorithm to extract generalizable, reusable features. To this end, we collected a dataset of 7200 demonstrations for 71 different kitchen-themed tasks, collected in 10 different environments (see the illustration in Figure 1). We refer to this dataset as the BRIDGE dataset (Broad Robot Interaction Dataset for boosting GEneralization)

To study how this dataset can be reused for multiple problems, we take a simple multi-task imitation learning approach to train vision-based control policies on our diverse multi-task, multi-domain dataset. Our experiments show that by reusing the BRIDGE dataset, we can enable a robot in a new scene or environment (which was not seen in the bridge data) to more effectively generalize when learning a new task (which was also not seen in the bridge data), as well as to transfer tasks from the bridge data to the target domain. Since we use a low-cost robotic arm, the setup can readily be reproduced by other researchers who can use our bridge dataset to boost the performance of their own robot policies.

With the proposed dataset and multi-task, multi-domain learning approach, we have shown one potential avenue for making diverse datasets reusable in robotics, opening up this area for more sophisticated techniques as well as providing the confidence that scaling up this approach could lead to even greater generalization benefits.

BRIDGE Dataset Specifics

Compared to existing datasets, including DAML, MIME, Robonet, RoboTurk, and Visual Imitation Made Easy, which mainly focus on a single scene or environment, our dataset features multiple domains and a large number of diverse, semantically meaningful tasks with expert trajectories, making it well suited for imitation learning and transfer learning on new domains.

The environments in the bridge dataset are mostly kitchen and sink playsets for children, since they are comparatively robust and low-cost, while still providing settings that resemble typical household scenes. The dataset was collected with 3-5 concurrent viewpoints to provide a form of data augmentation and study generalization to new viewpoints. Each task has between 50 and 300 demonstrations. To prevent algorithms from overfitting to certain positions, during data collection, we randomize the kitchen position, the camera positions, and the positions of distractor objects every 5-25 trajectories.

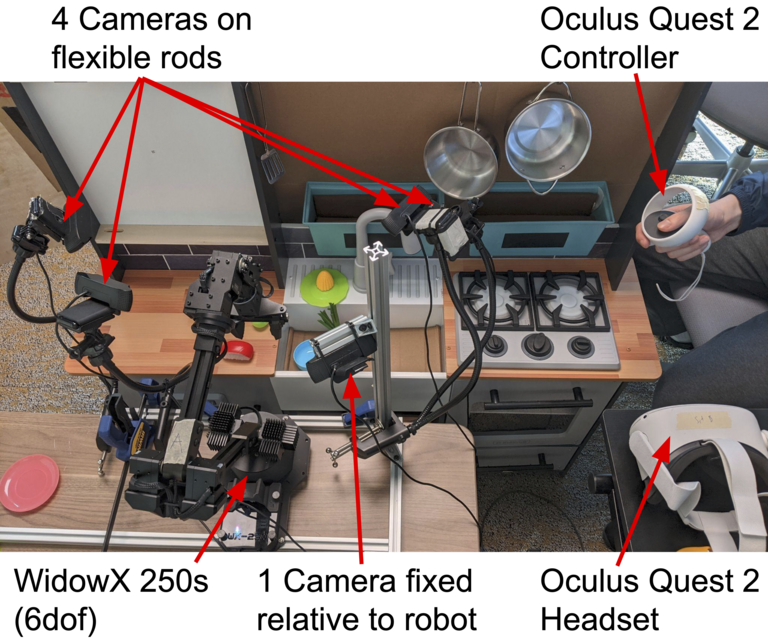

Fig 2: Demonstration data collection setup using VR Headset.

We collect our dataset with the 6-dof WidowX250s robot due to its accessibility and affordability, though we welcome contributions of data with different robots. The total cost of the setup is less than US$3600 (excluding the computer). To collect demonstrations, we use an Oculus Quest headset, where we put the headset on a table (as illustrated in Figure 2) next to the robot and track the user’s handset while applying the user’s motions to the robot end-effector via inverse kinematics. This gives the user an intuitive method for controlling the arm in 6 degrees of freedom.

Instructions for how users can reproduce our setup and collect data in new environments can be found on the project website.

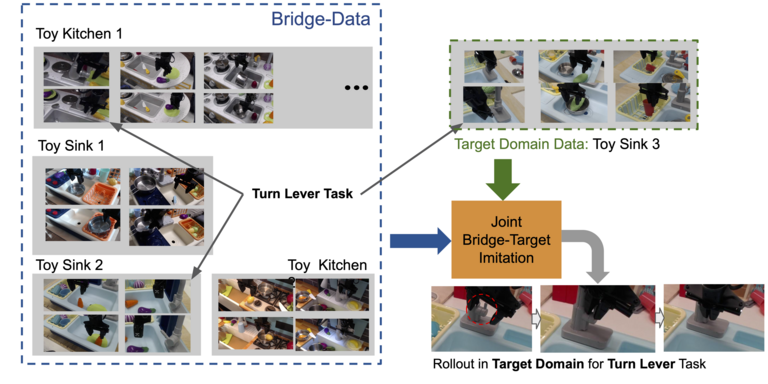

Transfer with Multi-Task Imitation Learning While a variety of transfer learning methods have been proposed in the literature for combining datasets from distinct domains, we find that a simple joint training approach is effective for deriving considerable benefit from bridge data. We combine the bridge dataset with user-provided demonstrations in the target domain. Since the sizes of these datasets are significantly different, we rebalance the datasets (for more details see the paper). Imitation learning then proceeds normally, simply training the policy with supervised learning on the combined dataset.

Boosting Generalization via Bridge Datasets We consider three types of generalization in our experiments:

Transfer with matching behaviors

Figure 4: Scenario 1, Transfer with matching behaviors: Here, the user collects a small number of demonstrations in the target domain for a task that is also present in the bridge data.

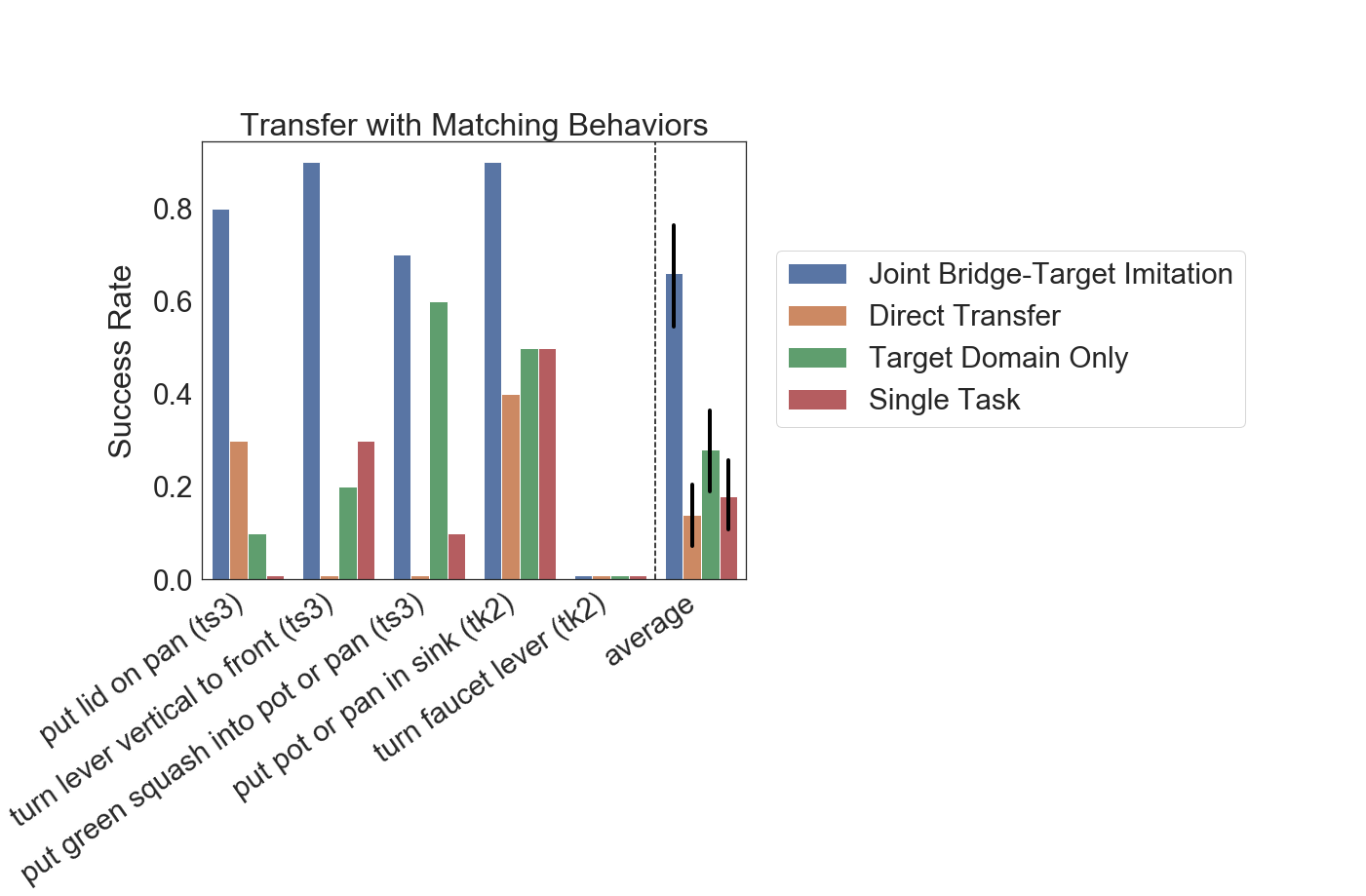

Figure 5: Experiment results for transfer with matching behaviors. Jointly training with the bridge data greatly improves generalization performance.

In this scenario (depicted in Figure 4), the user collects some small amount of data in their target domain for tasks that are also present in the bridge data (e.g., around 50 demos per task) and uses the bridge data to boost the performance and generalization of these tasks. This scenario is the most conventional and resembles domain adaptation in computer vision, but it is also the most limiting since it requires the desired tasks to be present in the bridge data and the user to collect additional data of the same task.

Figure 5 shows results for the transfer learning with matching behaviors scenario. For comparison, we include the performance of the policy when trained only on the target domain data, without bridge data (Target Domain Only), a baseline that uses only the bridge data without any target domain data (Direct Transfer), as well as a baseline that trains a single-task policy on data in the target domain only (Single Task). As can be seen in the results, jointly training with the bridge data leads to significant gains in performance (66% success averaged over tasks) compared to the direct transfer (14% success), target domain only (28% success), and the single task (18% success) baseline. This is not surprising since this scenario directly augments the training set with additional data of the same tasks, but it still provides a validation of the value of including bridge data in training.

Zero-shot transfer with target support

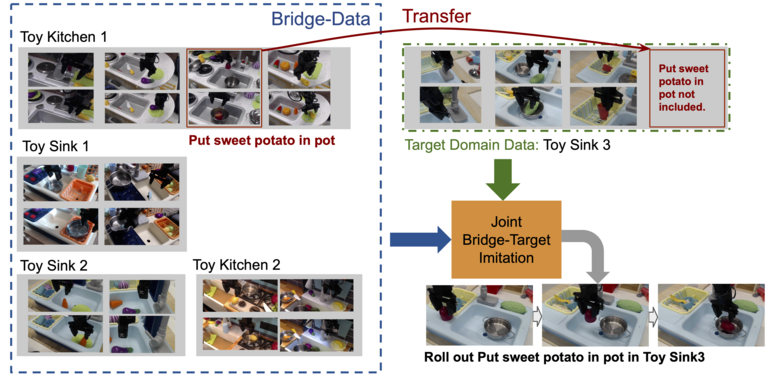

Figure 6: Scenario 2, Zero-shot transfer with target support: After collecting data for a small number of tasks (10 in our case) in the target domain, the user is able to transfer other tasks from the bridge dataset to the target domain.

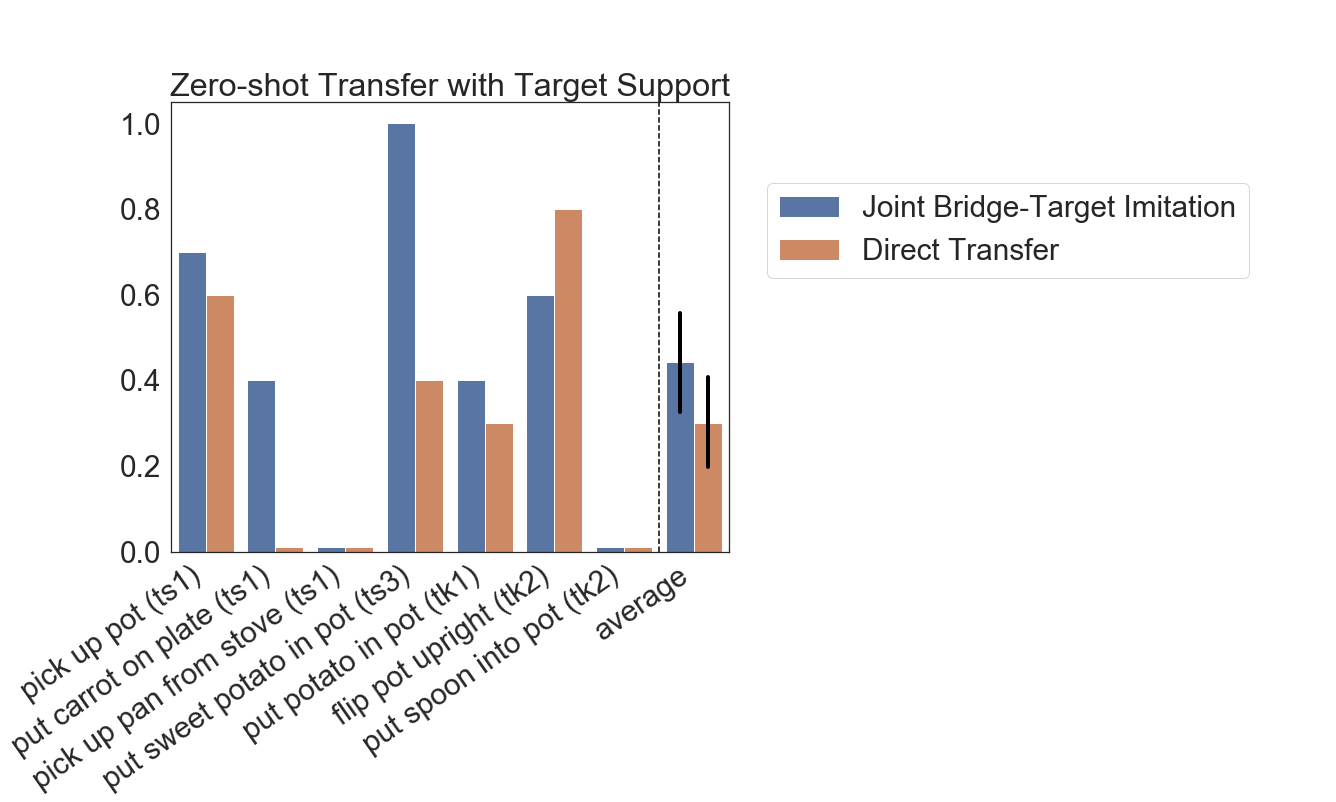

Figure 7: Experiment results for zero-shot transfer with target support: Joint bridge-target imitation, which is trained with bridge data and data from 10 target domain tasks, allows transferring tasks to the target domain with significantly higher success rates (blue) than directly transferring tasks (without any target domain data), called direct transfer (orange).

In this scenario (depicted in Figure 6), the user utilizes data from a few tasks in their target domain to “import” other tasks that are present in the bridge data without additionally collecting new demonstrations for them in the target domain. For example, the bridge data contains the tasks of putting a sweet potato into a pot or a pan, the user provides data in their domain for putting brushes in pans, and the robot is then able to both put brushes as well as put sweet potatoes in pans. This scenario increases the repertoires of skills that are available in the user’s target environment simply by including the bridge data, thus eliminating the need to recollect data for every task in every target environment.

Figure 7 shows the experiment results for this scenario. Since there is no target domain data for these tasks, we cannot compare to a baseline that does not use bridge data at all since such a baseline would have no data for these tasks. However, we do include the “direct transfer” baseline, which utilizes a policy trained only on the bridge data. The results indicate that the jointly trained policy, which obtains 44% success averaged over tasks indeed attains a very significant increase in performance over direct transfer (30% success), suggesting that the zero-shot transfer with target support scenario offers a viable way for users to “import” tasks from the bridge dataset into their domain.

Boosting generalization of new tasks

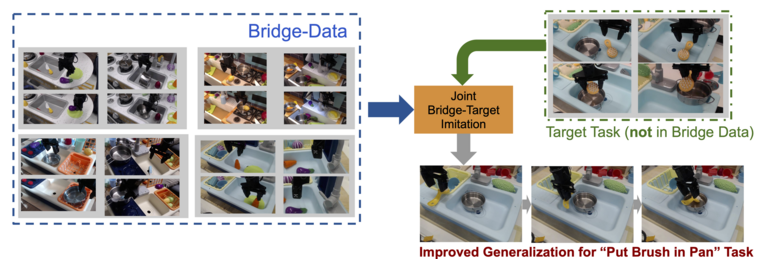

Figure 8:Scenario 3, Boosting generalization of new tasks: Jointly training with bridge data and a new task in a new scene or environment (that is not present in the bridge data) enables significantly higher success rates than training on the target domain data from scratch.

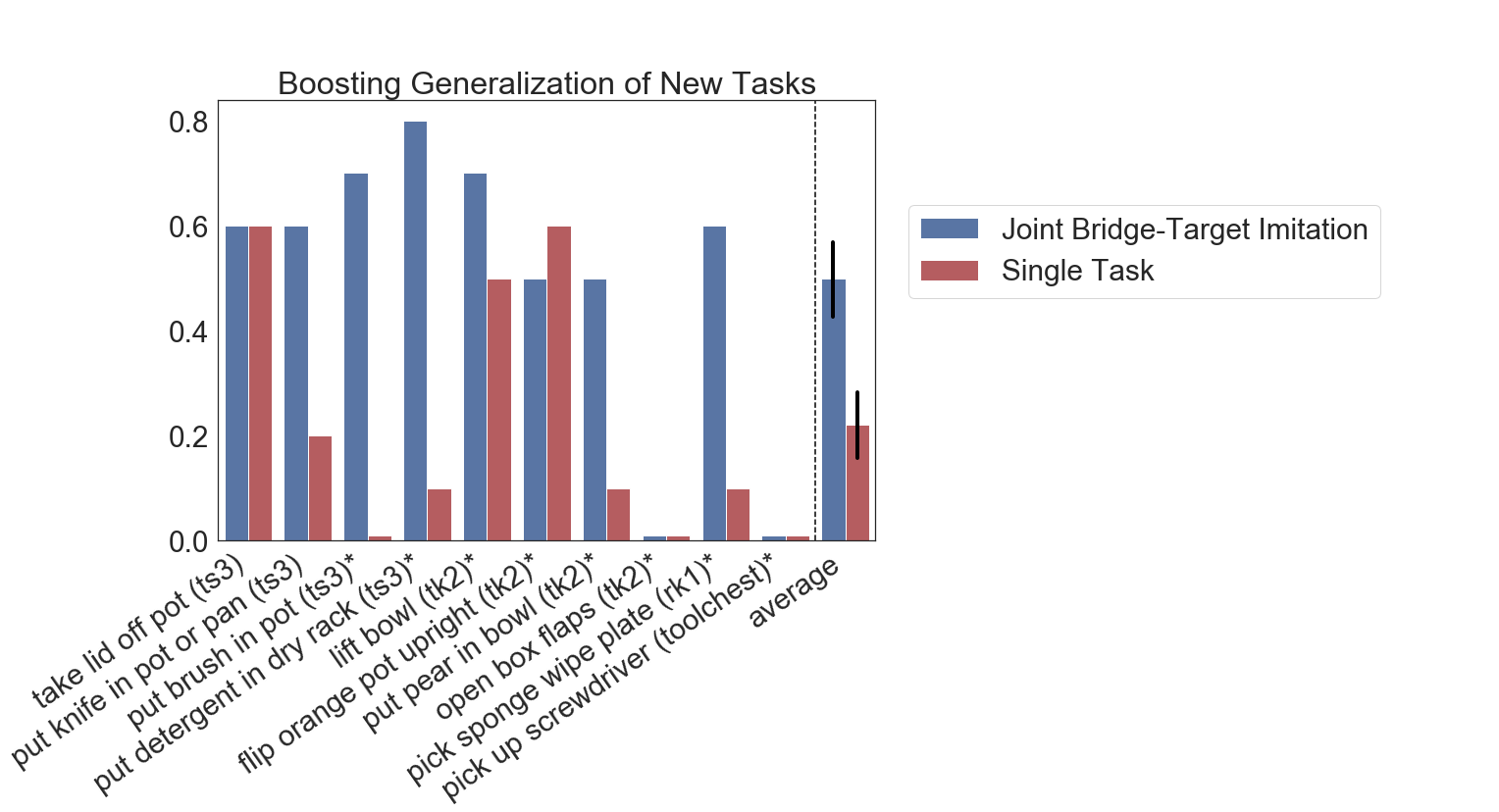

Figure 9: Experiment results for boosting generalization of new tasks: Jointly training with bridge data (blue) on average leads to a 2x gain in generalization performance compared to only training on target domain data (red).

In this scenario (depicted in Figure 8), the user provides a small amount of data (50 demonstrations in practice) for a new task that is not present in the bridge data and then utilizes the bridge data to boost the generalization and performance of this task. This scenario most directly reflects our primary goals since it uses the bridge data without requiring either the domains or tasks to match, leveraging the diversity of the data and structural similarity to boost performance and generalization of entirely new tasks.

To enable this kind of generalization boosting, we conjecture that the key features that bridge datasets must have are: (i) a sufficient variety of settings, so as to provide for good generalization; (ii) shared structure between bridge data domains and target domains (i.e., it is unreasonable to expect generalization for a construction robot using bridge data of kitchen tasks); (iii) a sufficient range of tasks that breaks unwanted correlations between tasks and domains.

The experiment results are presented in Figure 9, which show that training jointly with the bridge data leads to significant improvement on 6 out of 10 tasks across three evaluation environments, leading to 50% success averaged over tasks, whereas single task policies attain around 22% success – a 2x improvement in overall performance (the asterisks denote in which experiments the objects are not contained in the bridge data). The significant improvements obtained from including the bridge data suggest that bridge datasets can be a powerful vehicle for boosting the generalization of new skills and that a single shared bridge dataset can be utilized across a range of domains and applications.

In Figure 10 we show example rollouts for each of the three transfer scenarios.

Figure 10: Example rollouts of policies jointly trained on target domain data and bridge data in each of the three transfer scenarios.

Left: transfer with matching behaviors, scenario 1, put pot in sink;

Middle: zero-shot transfer with target support, scenario 2, put carrot on plate;

Right: boosting generalization of new tasks, scenario 3, wipe plate with sponge

Conclusions

We showed how a large, diverse bridge dataset can be leveraged in three different ways to improve generalization in robotic learning. Our experiments demonstrate that including bridge data when training skills in a new domain can improve performance across a range of scenarios, both for tasks that are present in the bridge data and, perhaps surprisingly, entirely new tasks. This means that bridge data may provide a generic tool to improve generalization in a user’s target domain. In addition, we showed that bridge data can also function as a tool to import tasks from the prior dataset to a target domain, thus increasing the repertoires of skills a user has at their disposal in a particular target domain. This suggests that a large, shared bridge dataset, like the one we have released, could be used by different robotics researchers to boost the generalization capabilities and the number of available skills of their imitation-trained policies.

We hope that by releasing our dataset to the community, we can take a step toward generalizing robotic learning and make it possible for anyone to train robotic policies that quickly generalize to varied environments without repeatedly collecting large and exhaustive datasets.

We encourage interested researchers to visit our project website for more information and instructions for how to contribute to our dataset.

Please find the corresponding paper on arxiv. We thank Chelsea Finn and Sergey Levine for helpful feedback on the blog post.

This post is based on the following paper:

Bridge Data: Boosting Generalization of Robotic Skills with Cross-Domain Datasets

Frederik Ebert\(^*\), Yanlai Yang\(^*\), Karl Schmeckpeper, Bernadette Bucher, Georgios Georgakis, Kostas Daniilidis, Chelsea Finn, Sergey Levine

paper, project website