Cross-posted from Bounded Regret.

Earlier this year, my research group commissioned 6 questions for professional forecasters to predict about AI. Broadly speaking, 2 were on geopolitical aspects of AI and 4 were on future capabilities:

- Geopolitical:

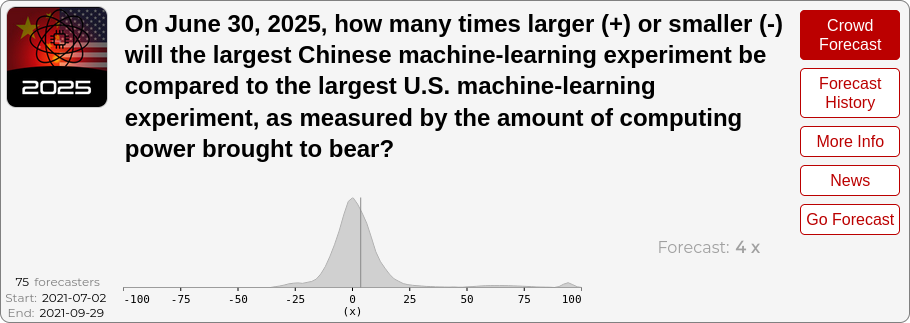

- How much larger or smaller will the largest Chinese ML experiment be compared to the largest U.S. ML experiment, as measured by amount of compute used?

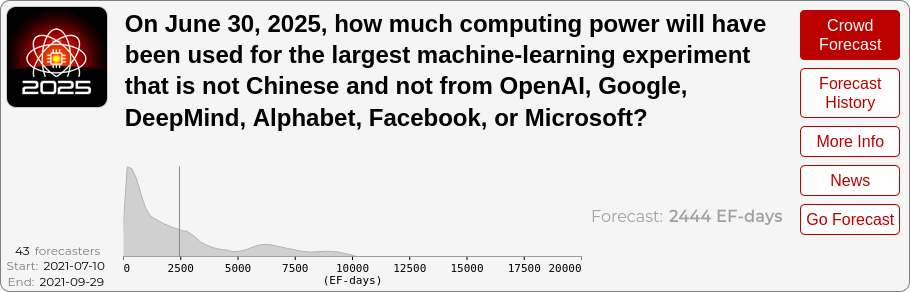

- How much computing power will have been used by the largest non-incumbent (OpenAI, Google, DeepMind, FB, Microsoft), non-Chinese organization?

- Future capabilities:

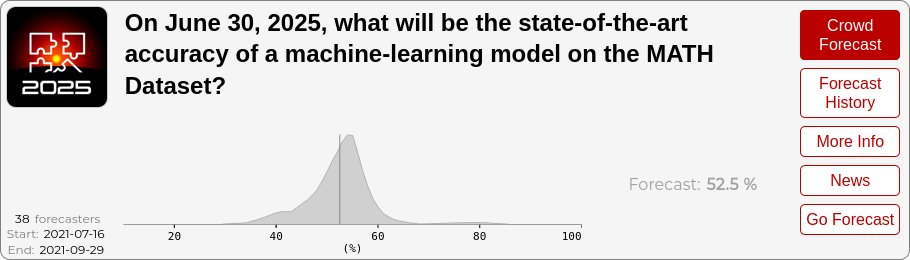

- What will SOTA (state-of-the-art accuracy) be on the MATH dataset?

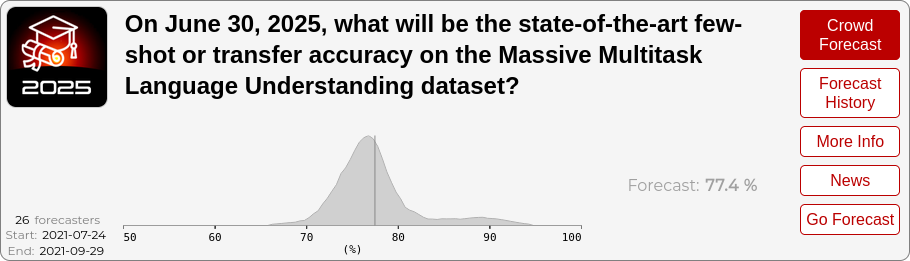

- What will SOTA be on the Massive Multitask dataset (a broad measure of specialized subject knowledge, based on high school, college, and professional exams)?

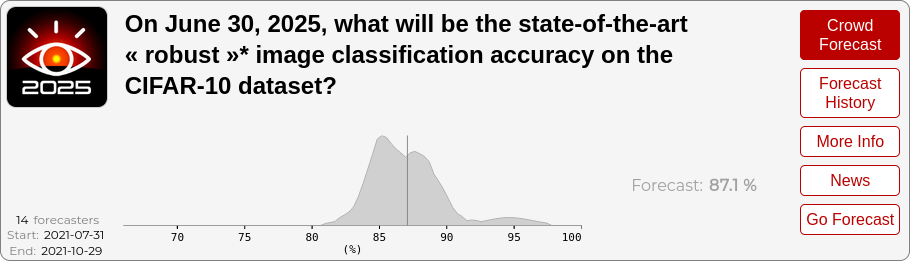

- What will be the best adversarially robust accuracy on CIFAR-10?

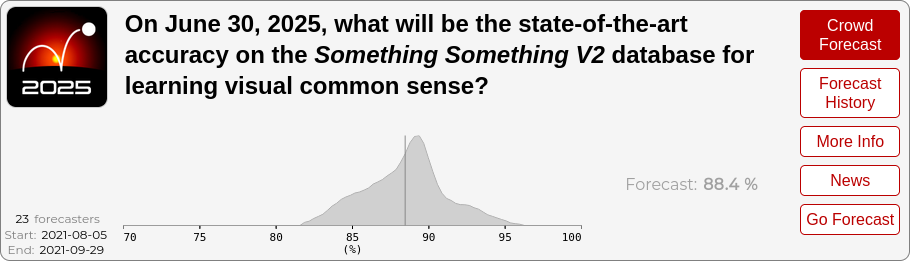

- What will SOTA be on Something Something v2? (A video recognition dataset)

Forecasters output a probability distribution over outcomes for 2022, 2023, 2024, and 2025. They have financial incentives to produce accurate forecasts; the rewards total \$5k per question (\$30k total) and payoffs are (close to) a proper scoring rule, meaning forecasters are rewarded for outputting calibrated probabilities.

Depending on who you are, you might have any of several questions:

- What the heck is a professional forecaster?

- Has this sort of thing been done before?

- What do the forecasts say?

- Why did we choose these questions?

- What lessons did we learn?

You’re in luck, because I’m going to answer each of these in the following sections! Feel free to skim to the ones that interest you the most.

And before going into detail, here were my biggest takeaways from doing this:

- Projected progress on math and on broad specialized knowledge are both faster than I would have expected. I now expect more progress in AI over the next 4 years than I did previously.

- The relative dominance of the U.S. vs. China is uncertain to an unsettling degree. Forecasters are close to 50-50 on who will have more compute directed towards AI, although they do at least expect it to be within a factor of 10 either way.

- It’s difficult to come up with forecasts that reliably track what you intuitively care about. Organizations might stop reporting compute estimates for competitive reasons, which would confound both of the geopolitical metrics. They might similarly stop publishing the SOTA performance of their best models, or do it on a lag, which could confound the other metrics as well. I discuss these and other issues in the “Lessons learned” section.

- Professional forecasting seems really valuable and underincentivized. (On that note, I’m interested in hiring forecasting consultants for my lab–please e-mail me if you’re interested!)

Acknowledgments. The particular questions were designed by my students Alex Wei, Collin Burns, Jean-Stanislas Denain, and Dan Hendrycks. Open Philanthropy provided the funding for the forecasts, and Hypermind ran the forecasting competition and constructed the aggregate summaries that you see below. Several people provided useful feedback on this post, especially Luke Muehlhauser and Emile Servan-Schreiber.

What is a professional forecaster? Has this been done before?

Professional forecasters are individuals, or often teams, who make money by placing accurate predictions in prediction markets or forecasting competitions. A good popular treatment of this is Philip Tetlock’s book Superforecasting, but the basic idea is that there are a number of general tools and skills that can improve prediction ability and forecasters who practice these usually outperform even domain experts (though most strong forecasters have some technical background and will often read up on the domain they are predicting in). Historically, many forecasts were about geopolitical events (perhaps reflecting government funding interest), but there have been recent forecasting competitions about Covid-19 and the future of food, among others.

At this point, you might be skeptical. Isn’t predicting the future really hard, and basically impossible? An important thing to realize here is that forecasters usually output probabilities over outcomes, rather than a single number. So while I probably can’t tell you what US GDP will be in 2025, I can give you a probability distribution. I’m personally pretty confident it will be more than \$700 billion and less than \$700 trillion (it’s currently $21 trillion), although a professional forecaster would do much better than that.

There are a couple other important points here. The first is that forecasters’ probability distributions are often significantly wider than the sorts of things you’d see pundits on TV say (if they even bother to venture a range rather than a single number). This reflects the future actually being quite uncertain, but even a wide range can be informative, and sometimes I see forecasted ranges that are a lot narrower than I expected.

The other point is that most forecasts are for at most a year or two into the future. Recently there have been some experimental attempts to forecast out to 2030, but I’m not sure we can say yet how successful they were. Our own forecasts go out to 2025, so we aren’t as ambitious as the 2030 experiments, but we’re still avant-garde compared to the traditional 1-2 year window. If you’re interested in what we currently know about the feasibility of long-range forecasting, I recommend this detailed blog post by Luke Muehlhauser.

So, to summarize, a professional forecaster is someone who is paid to make accurate probabilistic forecasts about the future. Relative to pundits, they express significantly more uncertainty. The moniker “professional” might be a misnomer, since most income comes from prizes and I’d guess that most forecasters have a day job that produces most of their income. I’d personally love to live in a world with truly professional forecasters who could fully specialize in this important skill.

Other forecasting competitions. Broadly, there are all sorts of forecasting competitions, often hosted on Hypermind, Metaculus, or Good Judgment. There are also prediction markets (e.g. PredictIt), which are a bit different but also incentivize accurate predictions. Specifically on AI, Metaculus had a recent AI prediction tournament, and Hypermind ran the same questions on their own platform (AI2023, AI2030). I’ll discuss below how some of our questions relate to the AI2023 tournament in particular.

What the forecasts say

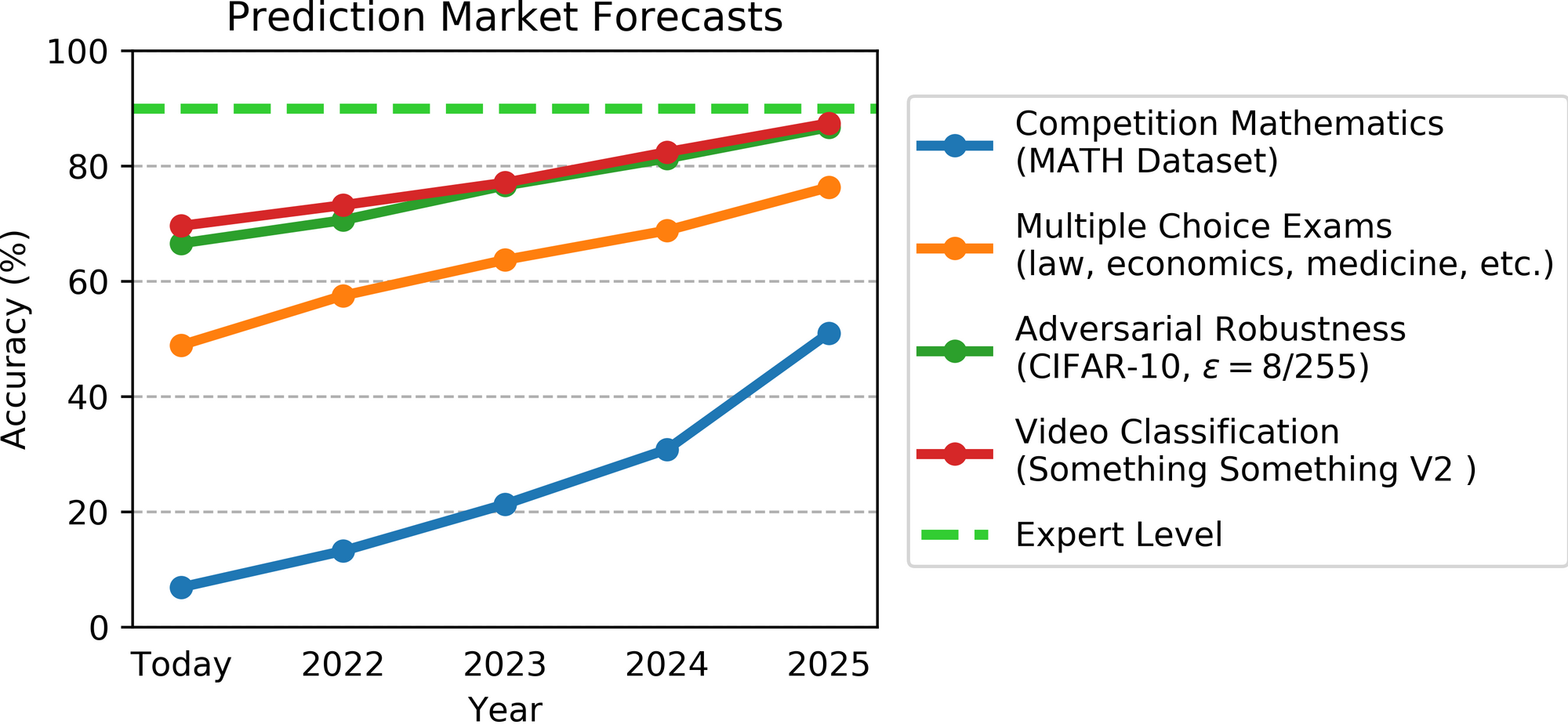

Here are the point estimate forecasts put together into a single chart (expert-level is approximated as ~90%):

The MATH and Multitask results were the most interesting to me, as they predict rapid progress starting from a low present-day baseline. I’ll discuss these in detail in the following subsections, and then summarize the other tasks and forecasts.

To get a sense of the uncertainty spread, I’ve also included aggregate results below (for 2025) on each of the 6 questions; you can find the results for other years here. The aggregate combines all crowd forecasts but places higher weight on forecasters with a good track record.

MATH

The MATH dataset consists of competition math problems for high school students. A Berkeley PhD student got in the ~75% range, while an IMO gold medalist got ~90%, but probably would have gotten 100% without arithmetic errors. The questions are free-response and not multiple-choice, and can contain answers such as $\frac{1 + \sqrt{2}}{2}$.

Current performance on this dataset is quite low–6.9%–and I expected this task to be quite hard for ML models in the near future. However, forecasters predict more than 50% accuracy* by 2025! This was a big update for me. (*More specifically, their median estimate is 52%; the confidence range is ~40% to 60%, but this is potentially artifically narrow due to some restrictions on how forecasts could be input into the platform.)

To get some flavor, here are 5 randomly selected problems from the “Counting and Probability” category of the benchmark:

- How many (non-congruent) isosceles triangles exist which have a perimeter of 10 and integer side lengths?

- A customer ordered 15 pieces of gourmet chocolate. The order can be packaged in small boxes that contain 1, 2 or 4 pieces of chocolate. Any box that is used must be full. How many different combinations of boxes can be used for the customer’s 15 chocolate pieces? One such combination to be included is to use seven 2-piece boxes and one 1-piece box.

- A theater group has eight members, of which four are females. How many ways are there to assign the roles of a play that involve one female lead, one male lead, and three different objects that can be played by either gender?

- What is the value of $101^{3} - 3 \cdot 101^{2} + 3 \cdot 101 -1$?

- 5 white balls and $k$ black balls are placed into a bin. Two of the balls are drawn at random. The probability that one of the drawn balls is white and the other is black is $\frac{10}{21}$. Find the smallest possible value of $k$.

Here are 5 randomly selected problems from the “Intermediate Algebra” category (I skipped one that involved a diagram):

- Suppose that $x$, $y$, and $z$ satisfy the equations $xyz = 4$, $x^3 + y^3 + z^3 = 4$, $xy^2 + x^2 y + xz^2 + x^2 z + yz^2 + y^2 z = 12$. Calculate the value of $xy + yz + zx$.

- If $\|z\| = 1$, express $\overline{z}$ as a simplified fraction in terms of $z$.

- In the coordinate plane, the graph of $\|x + y - 1\| + \|\|x\| - x\| + \|\|x - 1\| + $ $x - 1\| = 0$ is a certain curve. Find the length of this curve.

- Let $\alpha$, $\beta$, $\gamma$, and $\delta$ be the roots of $x^4 + kx^2 + 90x - 2009 = 0$. If $\alpha \beta = 49$, find $k$.

- Let $\tau = \frac{1 + \sqrt{5}}{2}$, the golden ratio. Then $\frac{1}{\tau} + \frac{1}{\tau^2} + \frac{1}{\tau^3} + \dotsb = \tau^n$ for some integer $n$. Find $n$.

You can see all of the questions at this git repo.

If I imagine an ML system getting more than half of these questions right, I would be pretty impressed. If they got 80% right, I would be super-impressed. The forecasts themselves predict accelerating progress through 2025 (21% in 2023, then 31% in 2024 and 52% in 2025), so 80% by 2028 or so is consistent with the predicted trend. This still just seems wild to me and I’m really curious how the forecasters are reasoning about this.

Multitask

The Massive Multitask dataset also consists of exam questions, but this time they are a range of high school, college, and professional exams on 57 different subjects, and these are multiple choice (4 answer choices total). Here are five example questions:

- (Jurisprudence) Which position does Rawls claim is the least likely to be adopted by the POP (people in the original position)?

- (A) The POP would choose equality above liberty.

- (B) The POP would opt for the ‘maximin’ strategy.

- (C) The POP would opt for the ‘difference principle.’

- (D) The POP would reject the ‘system of natural liberty.

- (Philosophy) According to Moore’s “ideal utilitarianism,” the right action is the one that brings about the greatest amount of:

- (A) pleasure. (B) happiness. (C) good. (D) virtue.

- (College Medicine) In a genetic test of a newborn, a rare genetic disorder is found that has X-linked recessive transmission. Which of the following statements is likely true regarding the pedigree of this disorder?

- (A) All descendants on the maternal side will have the disorder.

- (B) Females will be approximately twice as affected as males in this family.

- (C) All daughters of an affected male will be affected.

- (D) There will be equal distribution of males and females affected.

- (Conceptual Physics) A model airplane flies slower when flying into the wind and faster with wind at its back. When launched at right angles to the wind, a cross wind, its groundspeed compared with flying in still air is

- (A) the same (B) greater (C) less (D) either greater or less depending on wind speed

- (High School Statistics) Jonathan obtained a score of 80 on a statistics exam, placing him at the 90th percentile. Suppose five points are added to everyone’s score. Jonathan’s new score will be at the

- (A) 80th percentile.

- (B) 85th percentile.

- (C) 90th percentile.

- (D) 95th percentile.

Compared to MATH, these involve significantly less reasoning but more world knowledge. I don’t know the answers to these questions (except the last one), but I think I could figure them out with access to Google. In that sense, it would be less mind-blowing if an ML system did well on this task, although it would be accomplishing an intellectual feat that I’d guess very few humans could accomplish unaided.

The actual forecast is that ML systems will be around 75% on this by 2025 (range is roughly 70-85, with some right-tailed uncertainty). I don’t find this as impressive/wild as the MATH forecast, but it’s still pretty impressive.

My overall take from this task and the previous one is that forecasters are pretty confident that we won’t have the singularity before 2025, but at the same time there will be demonstrated progress in ML that I would expect to convince a significant fraction of skeptics (in the sense that it will look untenable to hold positions that “Deep learning can’t do X”).

Finally, to give an example of some of the harder types of questions (albeit not randomly selected), here are two from Professional Law and College Physics:

- (College Physics) One end of a Nichrome wire of length 2L and cross-sectional area A is attached to an end of another Nichrome wire of length L and cross- sectional area 2A. If the free end of the longer wire is at an electric potential of 8.0 volts, and the free end of the shorter wire is at an electric potential of 1.0 volt, the potential at the junction of the two wires is most nearly equal to

- (A) 2.4 V (B) 3.3 V (C) 4.5 V (D) 5.7 V

- (Professional Law) The night before his bar examination, the examinee’s next-door neighbor was having a party. The music from the neighbor’s home was so loud that the examinee couldn’t fall asleep. The examinee called the neighbor and asked her to please keep the noise down. The neighbor then abruptly hung up. Angered, the examinee went into his closet and got a gun. He went outside and fired a bullet through the neighbor’s living room window. Not intending to shoot anyone, the examinee fired his gun at such an angle that the bullet would hit the ceiling. He merely wanted to cause some damage to the neighbor’s home to relieve his angry rage. The bullet, however, ricocheted off the ceiling and struck a partygoer in the back, killing him. The jurisdiction makes it a misdemeanor to discharge a firearm in public. The examinee will most likely be found guilty for which of the following crimes in connection to the death of the partygoer?

- (A) Murder (B) Involuntary manslaughter (C) Voluntary manslaughter (D) Discharge of a firearm in public

You can view all the questions at this git repo.

Other questions

The other four questions weren’t quite as surprising, so I’ll go through them more quickly.

SOTA robustness: The forecasts expect consistent progress at ~7% per year. In retrospect this one was probably not too hard to get just from trend extrapolation. (SOTA was 44% in 2018 and 66% in 2021, with smooth-ish progress in-between.)

US vs. China: Forecasters have significant uncertainty in both directions, skewed towards the US being ahead in the next 2 years and China after that (seemingly mainly due to heavier-tailed uncertainty), but either one could be ahead and up to 10x the other. One challenge in interpreting this is that either country might stop publishing compute results if they view it as a competitive advantage in national security (or individual companies might do the same for competitive reasons).

Incumbents vs. rest of field: forecasters expect newcomers to increase size by ~10x per year for the next 4 years, with a central estimate of 21 EF-days in 2023. Note the AI2023 results predict the largest experiment by anyone (not just newcomers) to be 261EFLOP-s days in 2023, so this expects newcomers to be ~10x behind the incumbents, but only 1 year behind. This is also an example where forecasters have significant uncertainty–newcomers in 2023 could easily be in single-digit EF-days, or at 75 EF-days. In retrospect I wish I had included Anthropic on the list, as they are a new “big-compute” org that could be driving some fraction of the results, and who I wouldn’t have intended to count as a newcomer (since they already exist).

Video understanding: Forecasters expect us to hit 88% accuracy (range: ~82%-95%) in 2025. In addition, they expect accuracy to increase at roughly 5%/year (though this presumably has to level off soon after 2025). This is faster than ImageNet, which has only been increasing at roughly 2%/year. In retrospect this was an “easy” prediction in the sense that accuracy has increased by 14% from Jan’18 to Jan’21 (close to 5%/year), but it is also “bold” in the sense that progress since Jan’19 has been minimal. (Apparently forecasters are more inclined to average over the longest available time window.) In terms of implications, video recognition is one of the last remaining “instinctive” modalities that humans are very good at, other than physical tasks (grasping, locomotion, etc.). It looks like we’ll be pretty good at a “basic” version of it by 2025, for a task that I’d intuitively rate as less complex than ImageNet but about as complex as CIFAR-100. Based on vision and language I expect an additional 4-5 years to master the “full” version of the task, so expect ML to have mostly mastered video by 2030. As before, this simultaneously argues against “the singularity is near” but for “surprisingly fast, highly impactful progress”.

Why we chose these questions

We liked the AI2023 questions (the previous prediction contest), but felt there were a couple categories that were missing. One was geopolitical (the first 2 questions), but the other one was benchmarks that would be highly informative about progress. The AI2023 challenge includes forecasts about a number of benchmarks, e.g. Pascal, Cityscape, few-shot on Mini-ImageNet, etc. But there aren’t ones where, if you told me we’d have a ton of progress on them by 2025, it would update my model of the world significantly. This is because the tasks included in AI2023 are mostly in the regime where NNs do reasonably well and I expect gradual progress to continue. (I would have been surprised by the few-shot Mini-ImageNet numbers 3 years ago, but not since GPT-3 showed that few-shot works well at scale).

It’s not so surprising that the AI2023 benchmarks were primarily ones that ML already does well on, because most ML benchmarks are created to be plausibly tractable. To enable more interesting forecasts, we created our own “hard” benchmarks where significant progress would be surprising. This was the motivation behind the MATH and Multitask datasets (we created both of these ourselves). As mentioned, I was pretty surprised by how optimistic forecasters were on both tasks, which updated me downward a bit on the task difficulty but also upward on how much progress we should expect in the next 4 years.

The other two benchmarks already existed but were carefully chosen. Robust accuracy on CIFAR was based on the premise that adversarial robustness is really hard and we haven’t seen much progress–perhaps it’s a particularly difficult challenge, which would be worrying if we care about the safety of AI systems. Forecasters instead predicted steady progress, but in retrospect I could have seen this myself. Even though adversarial robustness “feels” hard (perhaps because I work on it and spend a lot of time trying to make it work better), the actual year-on-year numbers showed a pretty clear 7%/year improvement.

The last task, video recognition, is an area that not many people work in currently, as it seems challenging compared to images (perhaps due to hardware constraints). But it sounds like we should expect steady progress on it in the coming years.

Lessons learned

It can sometimes be surprisingly difficult to formalize questions that track an intuitive quantity you care about.

For instance, we initially wanted to include questions about economic impacts of AI, but were unable to. For instance, we wanted to ask “How much private vs. public investment will there be in AI?” But this runs into the question of what counts as investment–Do we count something like applying data science to agriculture? If you look at most metrics that you’d hope track this quantity, they include all sorts of weird things like that, and the weird things probably dominate the metric. We ran into similar issues for indicators of AI-based automation–e.g. do industrial robots on assembly lines count, even if they don’t use much AI? For many economic variables, short-term effects may also disort results (investment might drop because of a pandemic or other shock).

There were other cases where we did construct a question, but had to be careful about framing. We initially considered using parameters rather than compute for the two geopolitical questions, but it’s possible to achieve really high parameter counts in silly ways and some organizations might even do so for publicity (indeed we think this is already happening to some extent). Compute is harder to fake in the same way.

As discussed above, secrecy could cloud many of the metrics we used. Some organizations might not publish compute numbers for competitive reasons, and the same could be true of SOTA results on leaderboards. This is more likely if AI heats up significantly, so unfortunately I expect forecasts to be least reliable when we need them most. We could potentially get around this issue by interrogating forecasters’ actual reasoning, rather than just the final output.

I also came to appreciate the value of doing lots of legwork to create a good forecasting target. The MATH dataset obviously was a lot of work to assemble, but I’m really glad we did because it created the single biggest update for me. I think future forecasting efforts should more strongly consider this lever.

Finally, even while often expressing significant uncertainty, forecasters can make bold predictions. I’m still surprised that forecasters predicted 52% on MATH, when current accuracy is 7% (!). My estimate would have had high uncertainty, but I’m not sure the top end of my range would have included 50%. I assume the forecasters are right and not me, but I’m really curious how they got their numbers.

Because of the possibility of such surprising results, forecasting seems really valuable. I hope that there’s significant future investment in this area. Every organization that’s serious about the future should have a resident or consultant forecaster. I am putting my money where my mouth is and currently hiring forecasting consultants for my research group; please e-mail me if this sounds interesting to you.