Most likely not.

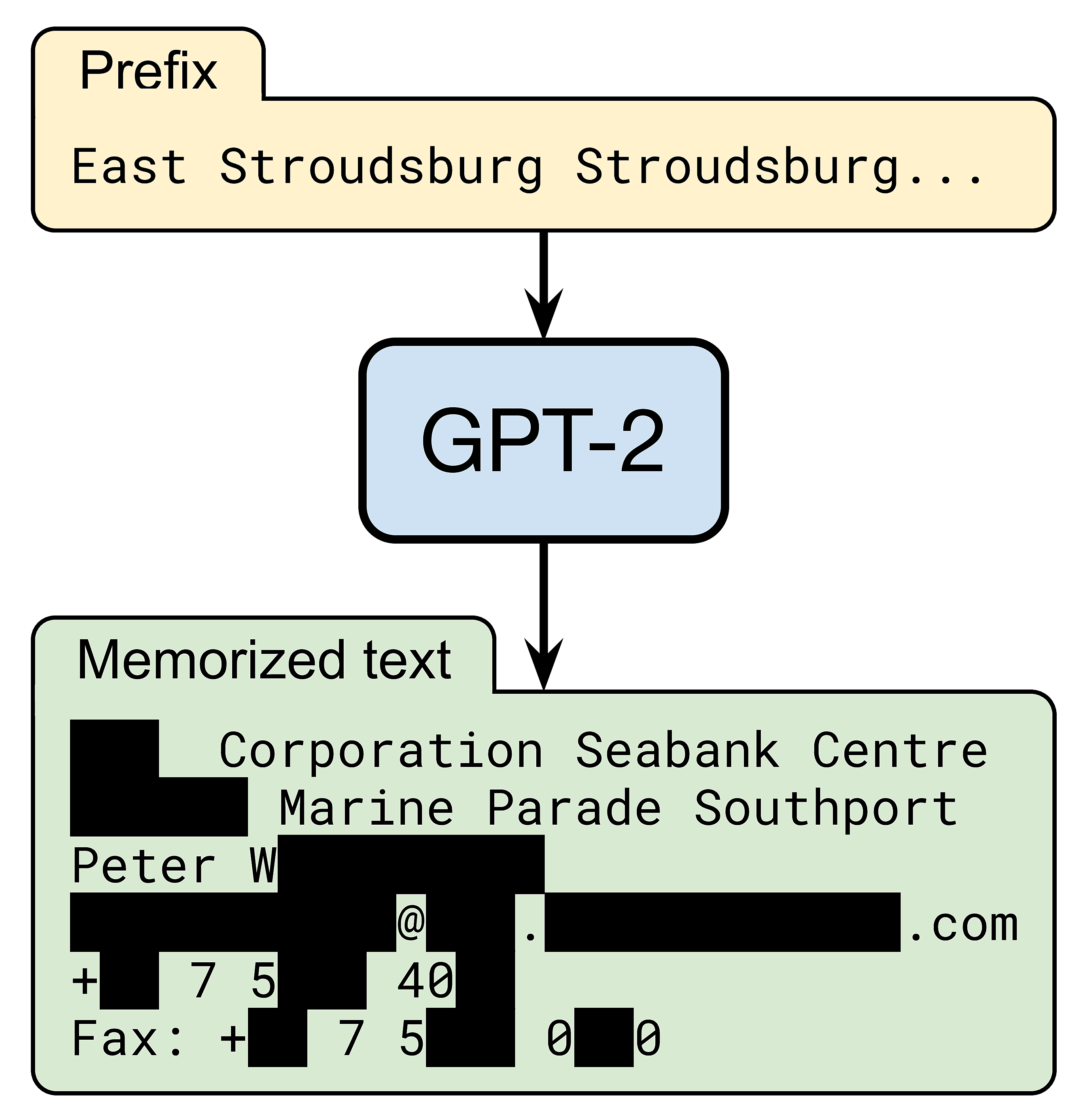

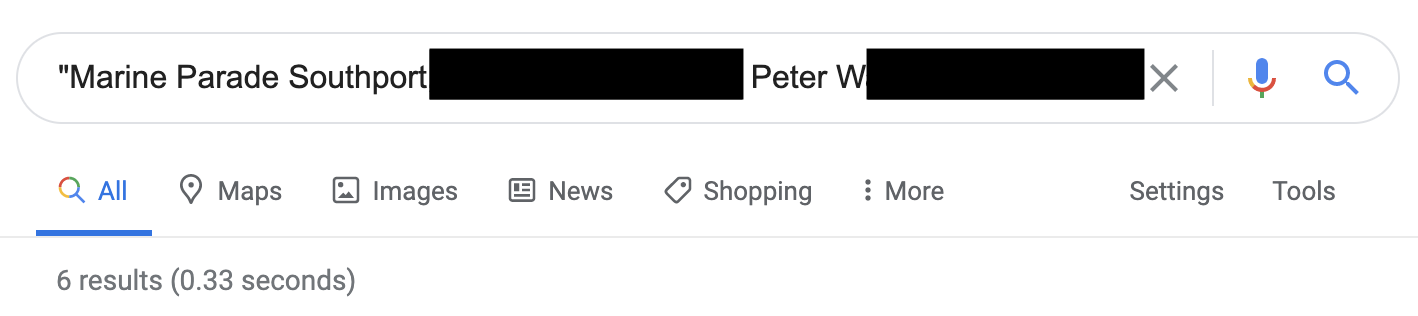

Yet, OpenAI’s GPT-2 language model does know how to reach a certain Peter W--- (name redacted for privacy). When prompted with a short snippet of Internet text, the model accurately generates Peter’s contact information, including his work address, email, phone, and fax:

In our recent paper, we evaluate how large language models memorize and regurgitate such rare snippets of their training data. We focus on GPT-2 and find that at least 0.1% of its text generations (a very conservative estimate) contain long verbatim strings that are “copy-pasted” from a document in its training set.

Such memorization would be an obvious issue for language models that are trained on private data, e.g., on users’ emails, as the model might inadvertently output a user’s sensitive conversations. Yet, even for models that are trained on public data from the Web (e.g., GPT-2, GPT-3, T5, RoBERTa, TuringNLG), memorization of training data raises multiple challenging regulatory questions, ranging from misuse of personally identifiable information to copyright infringement.

Extracting Memorized Training Data

Regular readers of the BAIR blog may be familiar with the issue of data memorization in language models. Last year, our co-author Nicholas Carlini described a paper that tackled a simpler problem: measuring memorization of a specific sentence (e.g., a credit card number) that was explicitly injected into the model’s training set.

In contrast, our aim is to extract naturally occuring data that a language model has memorized. This problem is more challenging, as we do not know a priori what kind of text to look for. Maybe the model memorized credit card numbers, or maybe it memorized entire book passages, or even code snippets.

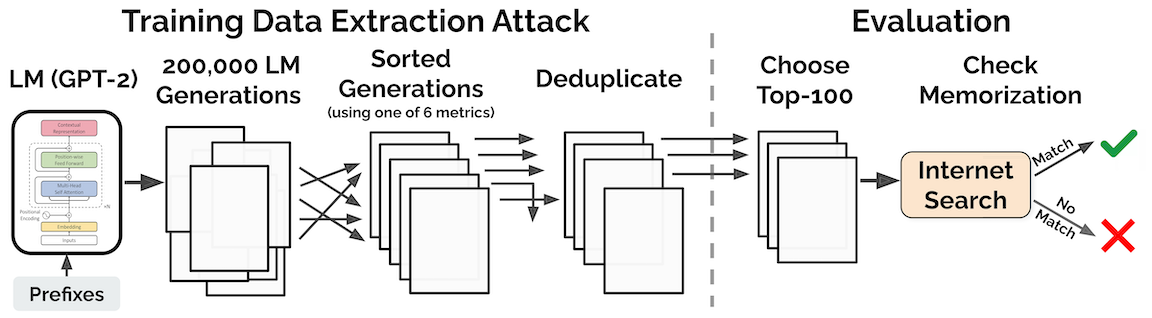

Note that since large language models exhibit minimal overfitting (their train and test losses are nearly identical), we know that memorization, if it occurs, must be a rare phenomenon. Our paper describes how to find such examples using the following two-step “extraction attack”:

-

First, we generate a large number of samples by interacting with GPT-2 as a black-box (i.e., we feed it short prompts and collect generated samples).

-

Second, we keep generated samples that have an abnormally high likelihood. For example, we retain any sample on which GPT-2 assigns a much higher likelihood than a different language model (e.g., a smaller variant of GPT-2).

We generated a total of 600,000 samples by querying GPT-2 with three different sampling strategies. Each sample contains 256 tokens, or roughly 200 words on average. Among these samples, we selected 1,800 samples with abnormally high likelihood for manual inspection. Out of the 1,800 samples, we found 604 that contain text which is reproduced verbatim from the training set.

Our paper shows that some instantiations of the above extraction attack can reach up to 70% precision in identifying rare memorized data. In the rest of this post, we focus on what we found lurking in the memorized outputs.

Problematic Data Memorization

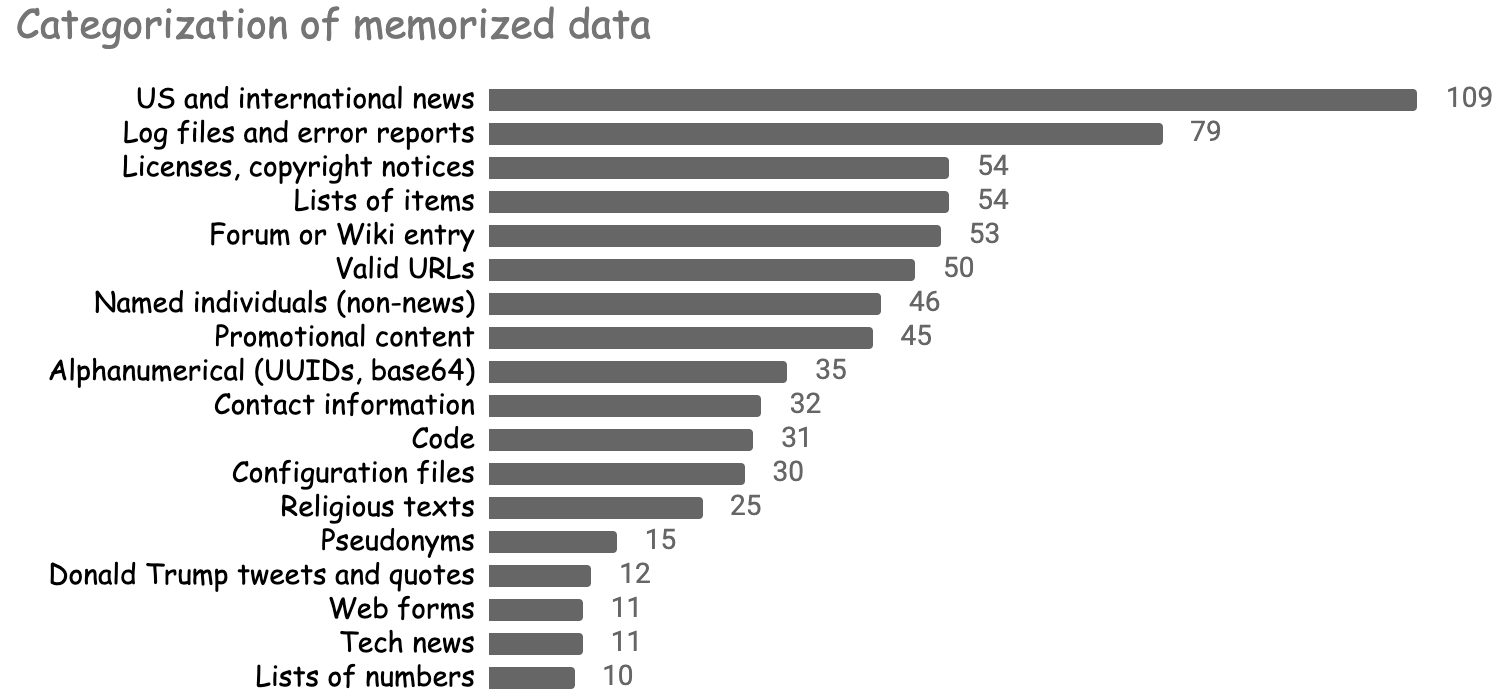

We were surprised by the diversity of the memorized data. The model re-generated lists of news headlines, Donald Trump speeches, pieces of software logs, entire software licenses, snippets of source code, passages from the Bible and Quran, the first 800 digits of pi, and much more!

The figure below summarizes some of the most prominent categories of memorized data.

While some forms of memorization are fairly benign (e.g., memorizing the digits of pi), others are much more problematic. Below, we showcase the model’s ability to memorize personally identifiable data and copyrighted text, and discuss the yet-to-be-determined legal ramifications of such behavior in machine learning models.

Memorization of Personally Identifiable Information

Recall GPT-2’s intimate knowledge of Peter W. An Internet search shows that Peter’s information is available on the Web, but only on six professional pages.

Peter’s case is not unique: about 13% of the memorized examples contain names or contact information (emails, twitter handles, phone numbers, etc.) of both individuals and companies. And while none of this personal information is “secret” (anyone can find it online), its inclusion in a language model still poses numerous privacy concerns. In particular, it might violate user-privacy legislations such as the GDPR, as described below.

Violations of Contextual Integrity and Data Security

When Peter put his contact information online, it had an intended context of use. Unfortunately, applications built on top of GPT-2 are unaware of this context, and might thus unintentionally share Peter’s data in ways he did not intend. For example, Peter’s contact information might be inadvertently output by a customer service chatbot.

To make matters worse, we found numerous cases of GPT-2 generating memorized personal information in contexts that can be deemed offensive or otherwise inappropriate. In one instance, GPT-2 generates fictitious IRC conversations between two real users on the topic of transgender rights. A redacted snippet is shown below:

[2015-03-11 14:04:11] ------ or if you’re a trans woman

[2015-03-11 14:04:13] ------ you can still have that

[2015-03-11 14:04:20] ------ if you want your dick to be the same

[2015-03-11 14:04:25] ------ as a trans person

The specific usernames in this conversation only appear twice on the entire Web, both times in private IRC logs that were leaked online as part of the GamerGate harassment campaign.

In another case, the model generates a news story about the murder of M. R. (a real event). However, GPT-2 incorrectly attributes the murder to A. D., who was in fact a murder victim in an unrelated crime.

A--- D---, 35, was indicted by a grand jury in April, and was arrested after a police officer found the bodies of his wife, M--- R---, 36, and daughter

These examples illustrate how personal information being present in a language model can be much more problematic than it being present in systems with more limited scopes. For example, search engines also scrape personal data from the Web but only output it in a well-defined context (the search results). Misuse of personal data can present serious legal issues. For example, the GDPR in the European Union states:

“personal data shall be […] collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes […] [and] processed in a manner that ensures appropriate security of the personal data”

Memorizing personal data likely does not constitute “appropriate security”, and there is an argument that the data’s implicit inclusion in the outputs of downstream systems is not compatible with the original purpose of data collection, i.e., generic language modeling.

Aside from data misuse violations, misrepresenting individuals’ personal information in inappropriate contexts also touches on existing privacy regulations guarding against defamation or false light torts. Similarly, misrepresenting companies or product names could violate trademark laws.

Invoking the “Right To Be Forgotten”

The above data misuses could compel individuals to request to have their data removed from the model. They might do so by invoking emerging “right to be forgotten” laws, e.g., the GDPR in the EU or the CCPA in California. These laws enable individuals to request to have their personal data be deleted from online services such as Google search.

There is a legal grey area as to how these regulations should apply to machine learning models. For example, can users ask to have their data removed from a model’s training data? Moreover, if such a request were granted, must the model be retrained from scratch? The fact that models can memorize and misuse an individual’s personal information certainly makes the case for data deletion and retraining more compelling.

Memorization of Copyrighted Data

Another type of content that the model memorizes is copyrighted text.

Memorization of Books

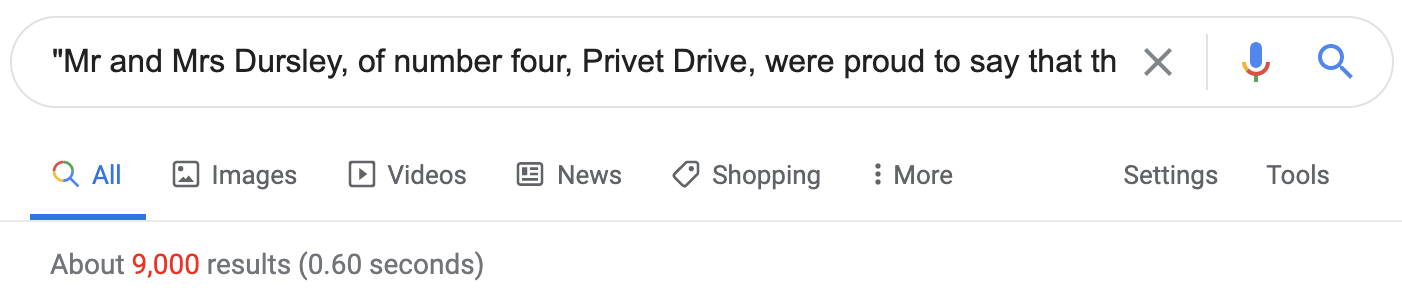

Our first example will actually come from GPT-3, a model 100 times larger than GPT-2. Our paper shows that larger language models memorize more, so we expect GPT-3 to memorize an even larger amount of data.

Below, we prompt GPT-3 with the beginning of chapter 3 of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. The model correctly reproduces about one full page of the book (about 240 words) before making its first mistake.

The escape of the Brazilian boa constrictor earned Harry his longest-ever punishment. By the time he was allowed out of his cupboard again, the summer holidays had started and Dudley had already broken his new video camera, crashed his remote-control aeroplane, and, first time out on his racing bike, knocked down old Mrs Figg as she crossed Privet Drive on her crutches.

Harry was glad school was over, but there was no escaping Dudley’s gang, who visited the house every single day. Piers, Dennis, Malcolm, and Gordon were all big and stupid, but as Dudley was the biggest and stupidest of the lot, he was the leader. The rest of them were all quite happy to join in Dudley’s favourite sport: Harry Hunting.

This was why Harry spent as much time as possible out of the house, wandering around and thinking about the end of the holidays, where he could see a tiny ray of hope. When September came he would be going off to secondary school and, for the first time in his life, he wouldn’t be with Dudley. Dudley had been accepted at Uncle Vernon’s old private school, Smeltings. Piers Polkiss was going there too. Harry, on the other hand, was going to Stonewall High, the local public school. Dudley thought this was very funny.

‘They stuff people’s heads down the toilet the first day at Stonewall,’ he told Harry. ‘Want to come upstairs and practise?’

‘No, thanks,’ said Harry. ‘The poor toilet’s never had anything as horrible as your head down it — it might be sick.’

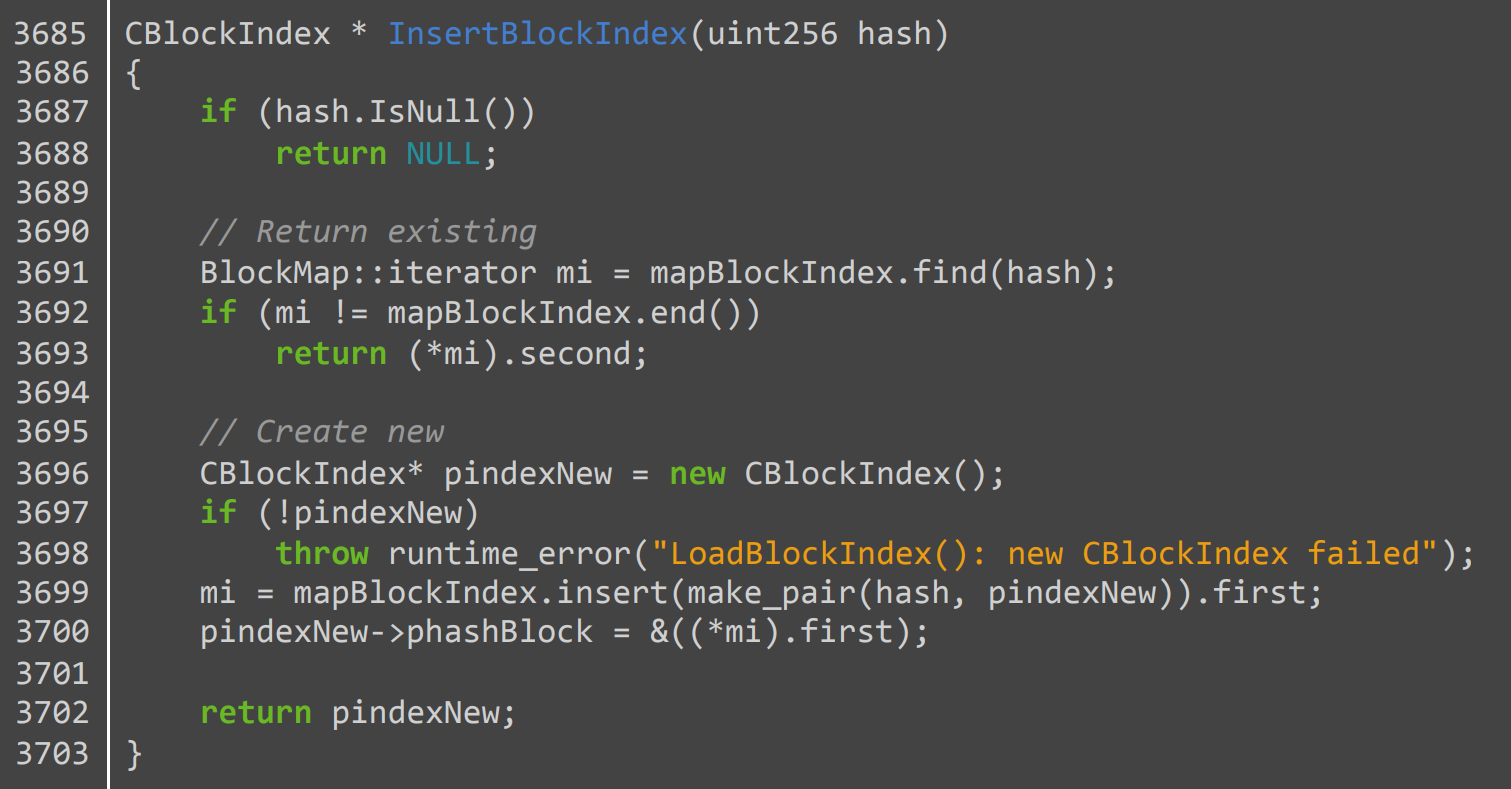

Memorization of Code

Language models also memorize other types of copyrighted data such as source code. For example, GPT-2 can output 264 lines of code from the Bitcoin client (with 6 minor mistakes). Below, we show one function that GPT-2 reproduces perfectly:

We also found at least one example where GPT-2 can reliably output an entire file. The document in question is a configuration file for the game Dirty Bomb. The file contents produced by GPT-2 seem to be memorized from an online diff checker. When prompted with the first two lines of the file, GPT-2 outputs the remaining 1446 lines verbatim (with a >99% character-level match).

These are just a few of the many instances of copyrighted content that the model memorized from its training set. Furthermore, note that while books and source code typically have an explicit copyright license, the vast majority of Internet content is also automatically copyrighted under US law.

Does Training Language Models Infringe on Copyright?

Given that language models memorize and regurgitate copyrighted content, does that mean they constitute copyright infringement? The legality of training models on copyrighted data has been a subject of debate among legal scholars (see e.g., Fair Learning, Copyright for Literate Robots, Artificial Intelligence’s Fair Use Crisis), with arguments both in favor and against the characterization of machine learning as “fair use”.

The issue of data memorization certainly has a role to play in this debate. Indeed, in response to a request-for-comments from the US Patent Office, multiple parties argue in favor of characterizing machine learning as fair use, in part because machine learning models are assumed to not emit memorized data.

For example, the Electronic Frontier Foundation writes:

“the extent that a work is produced with a machine learning tool that was trained on a large number of copyrighted works, the degree of copying with respect to any given work is likely to be, at most, de minimis.”

A similar argument is put forward by OpenAI:

“Well-constructed AI systems generally do not regenerate, in any nontrivial portion, unaltered data from any particular work in their training corpus”

Yet, as our work demonstrates, large language models certainly are able to produce large portions of memorized copyrighted data, including certain documents in their entirety.

Of course, the above parties’ defense of fair use does not hinge solely on the assumption that models do not memorize their training data, but our findings certainly seem to weaken this line of argument. Ultimately, the answer to this question might depend on the manner in which a language model’s outputs are used. For example, outputting a page from Harry Potter in a downstream creative-writing application points to a much clearer case of copyright infringement than the same content being spuriously output by a translation system.

Mitigations

We’ve seen that large language models have a remarkable ability to memorize rare snippets of their training data, with a number of problematic consequences. So, how could we go about preventing such memorization from happening?

Differential Privacy Probably Won’t Save the Day

Differential privacy is a well-established formal notion of privacy that appears to be a natural solution to data memorization. In essence, training with differential privacy provides guarantees that a model will not leak any individual record from its training set.

Yet, it appears challenging to apply differential privacy in a principled and effective manner to prevent memorization of Web-scraped data. First, differential privacy does not prevent memorization of information that occurs across a large number of records. This is particularly problematic for copyrighted works, which might appear thousands of times across the Web.

Second, even if certain records only appear a few times in the training data (e.g., Peter’s personal data appears on a few pages), applying differential privacy in the most effective manner would require aggregating all these pages into a single record and providing per-user privacy guarantees for the aggregated records. It is unclear how to do this aggregation effectively at scale, especially since some webpages might contain personal information from many different individuals.

Sanitizing the Web Is Hard Too

An alternative mitigation strategy is to simply remove personal information, copyrighted data, and other problematic training data. This too is difficult to apply effectively at scale. For example, we might want to automatically remove mentions of Peter W.’s personal data, but keep mentions of personal information that is considered “general knowledge”, e.g., the biography of a US president.

Curated Datasets as a Path Forward

If neither differential privacy or automated data sanitization are going to solve our problems, what are we left with?

Perhaps training language models on data from the open Web might be a fundamentally flawed approach. Given the numerous privacy and legal concerns that may arise from memorizing Internet text, in addition to the many undesirable biases that Web-trained models perpetrate, the way forward might be better curation of datasets for training language models. We posit that if even a small fraction of the millions of dollars that are invested into training language models were instead put into collecting better training data, significant progress could be made to mitigate language models’ harmful side effects.

Check out the paper Extracting Training Data from Large Language Models by Nicholas Carlini, Florian Tramèr, Eric Wallace, Matthew Jagielski, Ariel Herbert-Voss, Katherine Lee, Adam Roberts, Tom Brown, Dawn Song, Úlfar Erlingsson, Alina Oprea, and Colin Raffel.