Humans physically interact with each other every day – from grabbing someone’s hand when they are about to spill their drink, to giving your friend a nudge to steer them in the right direction, physical interaction is an intuitive way to convey information about personal preferences and how to perform a task correctly.

So why aren’t we physically interacting with current robots the way we do with each other? Seamless physical interaction between a human and a robot requires a lot: lightweight robot designs, reliable torque or force sensors, safe and reactive control schemes, the ability to predict the intentions of human collaborators, and more! Luckily, robotics has made many advances in the design of personal robots specifically developed with humans in mind.

However, consider the example from the beginning where you grab your friend’s hand as they are about to spill their drink. Instead of your friend who is spilling, imagine it was a robot. Because state-of-the-art robot planning and control algorithms typically assume human physical interventions are disturbances, once you let go of the robot, it will resume its erroneous trajectory and continue spilling the drink. The key to this gap comes from how robots reason about physical interaction: instead of thinking about why the human physically intervened and replanning in accordance with what the human wants, most robots simply resume their original behavior after the interaction ends.

We argue that robots should treat physical human interaction as useful information about how they should be doing the task. We formalize reacting to physical interaction as an objective (or reward) learning problem and propose a solution that enables robots to change their behaviors while they are performing a task according to the information gained during these interactions.

Reasoning About Physical Interaction: Unknown Disturbance versus Intentional Information

The field of physical human-robot interaction (pHRI) studies the design, control, and planning problems that arise from close physical interaction between a human and a robot in a shared workspace. Prior research in pHRI has developed safe and responsive control methods to react to a physical interaction that happens while the robot is performing a task. Proposed by Hogan et. al., impedance control is one of the most commonly used methods to move a robot along a desired trajectory when there are people in the workspace. With this control method, the robot acts like a spring: it allows the person to push it, but moves back to an original desired position after the human stops applying forces. While this strategy is very fast and enables the robot to safely adapt to the human’s forces, the robot does not leverage these interventions to update its understanding of the task. Left alone, the robot would continue to perform the task in the same way as it had planned before any human interactions.

Why is this the case? It boils down to what assumptions the robot makes about its knowledge of the task and the meaning of the forces it senses. Typically, a robot is given a notion of its task in the form of an objective function. This objective function encodes rewards for different aspects of the task like “reach a goal at location X” or “move close to the table while staying far away from people”. The robot uses its objective function to produce a motion that best satisfies all the aspects of the task: for example, the robot would move toward goal X while choosing a path that is far from a human and close to the table. If the robot’s original objective function was correct, then any physical interaction is simply a disturbance from its correct path. Thus, the robot should allow the physical interaction to perturb it for safety purposes, but it will return to the original path it planned since it stubbornly believes it is correct.

In contrast, we argue that human interventions are often intentional and occur because the robot is doing something wrong. While the robot’s original behavior may have been optimal with respect to its pre-defined objective function, the fact that a human intervention was necessary implies that the original objective function was not quite right. Thus, physical human interactions are no longer disturbances but rather informative observations about what the robot’s true objective should be. With this in mind, we take inspiration from inverse reinforcement learning (IRL), where the robot observes some behavior (e.g., being pushed away from the table) and tries to infer an unknown objective function (e.g., “stay farther away from the table”). Note that while many IRL methods focus on the robot doing better the next time it performs the task, we focus on the robot completing its current task correctly.

Formalizing Reacting to pHRI

With our insight on physical human-robot interactions, we can formalize pHRI as a dynamical system, where the robot is unsure about the correct objective function and the human’s interactions provide it with information. This formalism defines a broad class of pHRI algorithms, which includes existing methods such as impedance control, and enables us to derive a novel online learning method.

We will focus on two parts of the formalism: (1) the structure of the objective function and (2) the observation model that lets the robot reason about the objective given a human physical interaction. Let \(x\) be the robot’s state (e.g., position and velocity) and \(u_R\) be the robot’s action (e.g., the torque it applies to its joints). The human can physically interact with the robot by applying an external torque, called \(u_H\), and the robot moves to the next state via its dynamics, \(\dot{x} = f(x,u_R+u_H)\).

The Robot Objective: Doing the Task Right with Minimal Human Interaction

In pHRI, we want the robot to learn from the human, but at the same time we do not want to overburden the human with constant physical intervention. Hence, we can write down an objective for the robot that optimizes both completing the task and minimizing the amount of interaction required, ultimately trading off between the two.

\[r(x,u_R,u_H;\theta) = \theta^{\top} \phi(x,u_R,u_H) - ||u_H||^2\]Here, \(\phi(x,u_R,u_H)\) encodes the task-related features (e.g., “distance to table”, “distance to human”, “distance to goal”) and \(\theta\) determines the relative weight of each of these features. In the function, \(\theta\) encapsulates the true objective – if the robot knew exactly how to weight all the aspects of its task, then it could compute how to perform the task optimally. However, this parameter is not known by the robot! Robots will not always know the right way to perform a task, and certainly not the human-preferred way.

The Observation Model: Inferring the Right Objective from Human Interaction

As we have argued, the robot should observe the human’s actions to infer the unknown task objective. To link the direct human forces that the robot measures with the objective function, the robot uses an observation model. Building on prior work in maximum entropy IRL as well as the Bolzmann distributions used in cognitive science models of human behavior, we model the human’s interventions as corrections which approximately maximize the robot’s expected reward at state \(x\) while taking action \(u_R+u_H\). This expected reward emcompasses the immediate and future rewards and is captured by the \(Q\)-value:

\[P(u_H \mid x, u_R; \theta) \propto e^{Q(x,u_R+u_H;\theta)}\]Intuitively, this model says that a human is more likely to choose a physical correction that, when combined with the robot’s action, leads to a desirable (i.e., high-reward) behavior.

Learning from Physical Human-Robot Interactions in Real-Time

Much like teaching another human, we expect that the robot will continuously learn while we interact with it. However, the learning framework that we have introduced requires that the robot solve a Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP); unfortunately, it is well known that solving POMDPs exactly is at best computationally expensive, and at worst intractable. Nonetheless, we can derive approximations from this formalism that can enable the robot to learn and act while humans are interacting.

To achieve such in-task learning, we make three approximations summarized below:

1) Separate estimating the true objective from solving for the optimal control policy. This means at every timestep, the robot updates its belief over possible \(\theta\) values, and then re-plans an optimal control policy with the new distribution.

2) Separate planning from control. Computing an optimal control policy means computing the optimal action to take at every state in a continuous state, action, and belief space. Although re-computing a full optimal policy after every interaction is not tractable in real-time, we can re-compute an optimal trajectory from the current state in real-time. This means that the robot first plans a trajectory that best satisfies the current estimate of the objective, and then uses an impedance controller to track this trajectory. The use of impedance control here gives us the nice properties described earlier, where people can physically modify the robot’s state while still being safe during interaction.

Looking back at our estimation step, we will make a similar shift to trajectory space and modify our observation model to reflect this:

\[P(u_H \mid x, u_R; \theta) \propto e^{Q(x,u_R+u_H;\theta)} \rightarrow P(\xi_H \mid \xi_R; \theta) \propto e^{R(\xi_H, \xi_R;\theta)}\]Now, our observation model depends only on the cumulative reward \(R\) along a trajectory, which is easily computed by summing up the reward at each timestep. With this approximation, when reasoning about the true objective, the robot only has to consider the likelihood of a human’s preferred trajectory, \(\xi_H\), given the current trajectory it is executing, \(\xi_R\).

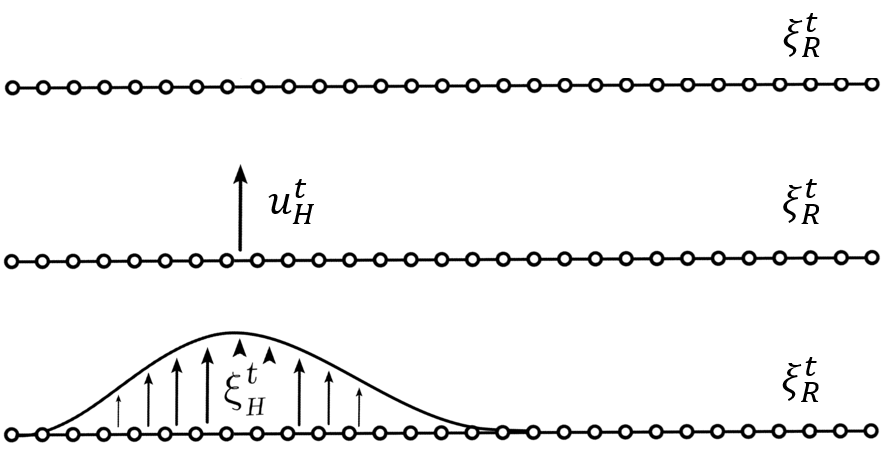

But what is the human’s preferred trajectory, \(\xi_H\)? The robot only gets to directly measure the human’s force $u_H$. One way to infer what is the human’s preferred trajectory is by propagating the human’s force throughout the robot’s current trajectory, \(\xi_R\). Figure 1. builds up the trajectory deformation based on prior work from Losey and O’Malley, starting from the robot’s original trajectory, then the force application, and then the deformation to produce \(\xi_H\).

Fig 1. To infer the human’s prefered trajectory given the current planned trajectory, the robot first measures the human’s interaction force, $u_H$, and then smoothly deforms the waypoints near interaction point to get the human’s preferred trajectory, $\xi_H$.

3) Plan with maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimate of \(\theta\). Finally, because \(\theta\) is a continuous variable and potentially high-dimensional, and since our observation model is not Gaussian, rather than planning with the full belief over \(\theta\), we will plan only with the MAP estimate. We find that the MAP estimate under a 2nd order Taylor Series Expansion about the robot’s current trajectory with a Gaussian prior is equivalent to running online gradient descent:

\[\theta^{t+1} = \theta^{t} + \alpha(\Phi(\xi^t_H) - \Phi(\xi^t_R))\]At every timestep, the robot updates its estimate of \(\theta\) in the direction of the cumulative feature difference, \(\Phi(\xi) = \sum_{x^t \in \xi} \phi(x^t)\), between its current optimal trajectory and the human’s preferred trajectory. In the Learning from Demonstration literature, this update rule is analogous to online Max Margin Planning; it is also analogous to coactive learning, where the user modifies waypoints for the current task to teach a reward function for future tasks.

Ultimately, putting these three steps together leads us to an elegant approximate solution to the original POMDP. At every timestep, the robot plans a trajectory \(\xi_R\) and begins to move. The human can physically interact, enabling the robot to sense their force $u_H$. The robot uses the human’s force to deform its original trajectory and produce the human’s desired trajectory, \(\xi_H\). Then the robot reasons about what aspects of the task are different between its original and the human’s preferred trajectory, and updates \(\theta\) in the direction of that difference. Using the new feature weights, the robot replans a trajectory that better aligns with the human’s preferences.

For a more thorough description of our formalism and approximations, please see our recent paper from the 2017 Conference on Robot Learning.

Learning from Humans in the Real World

To evaluate the benefits of in-task learning on a real personal robot, we recruited 10 participants for a user study. Each participant interacted with the robot running our proposed online learning method as well as a baseline where the robot did not learn from physical interaction and simply ran impedance control.

Fig 2. shows the three experimental household manipulation tasks, in each of which the robot started with an initially incorrect objective that participants had to correct. For example, the robot would move a cup from the shelf to the table, but without worrying about tilting the cup (perhaps not noticing that there is liquid inside).

Fig 2. Trajectory generated with initial objective marked in black, and the desired trajectory from true objective in blue. Participants need to correct the robot to teach it to hold the cup upright (left), move closer to the table (center), and avoid going over the laptop (right).

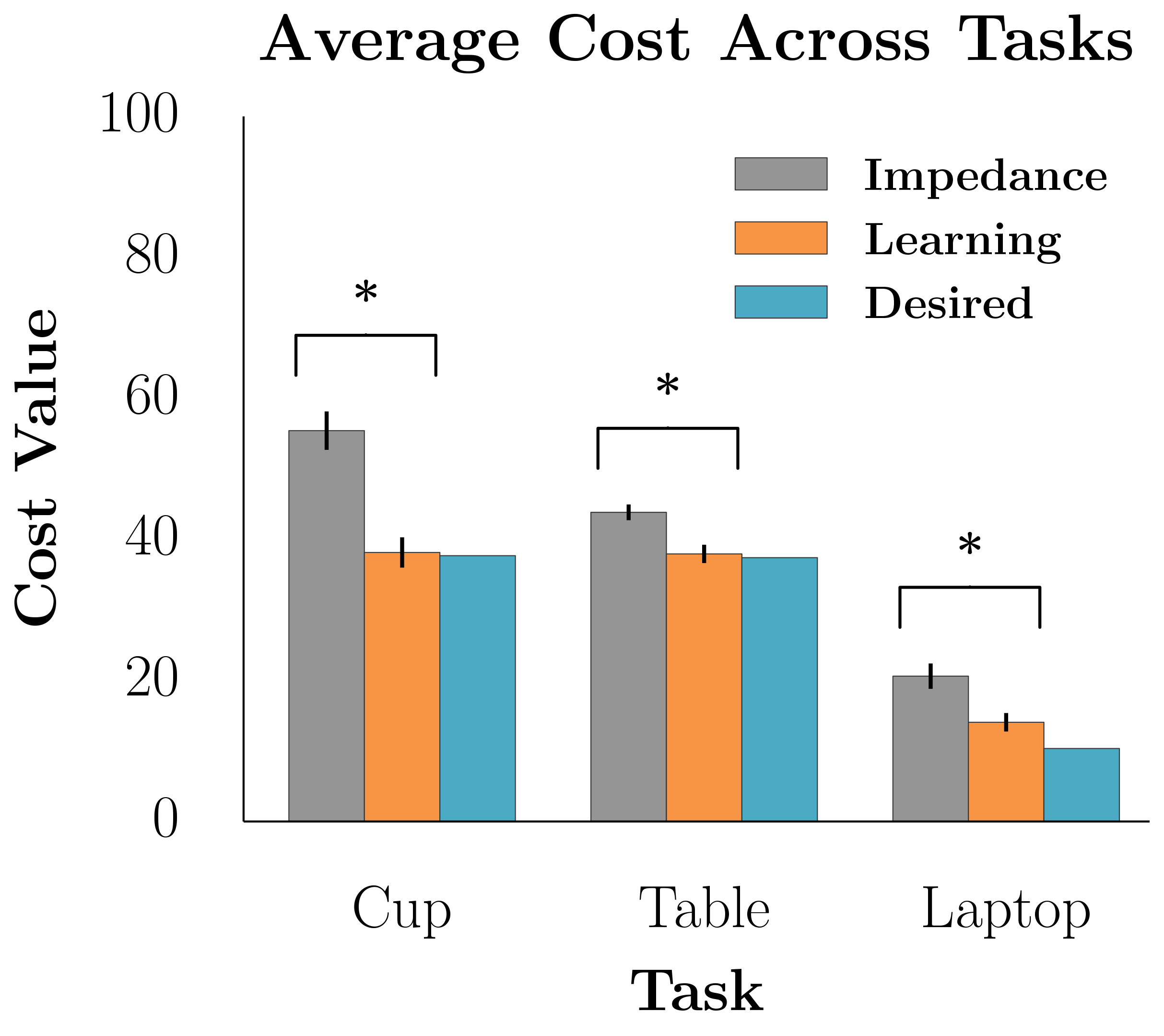

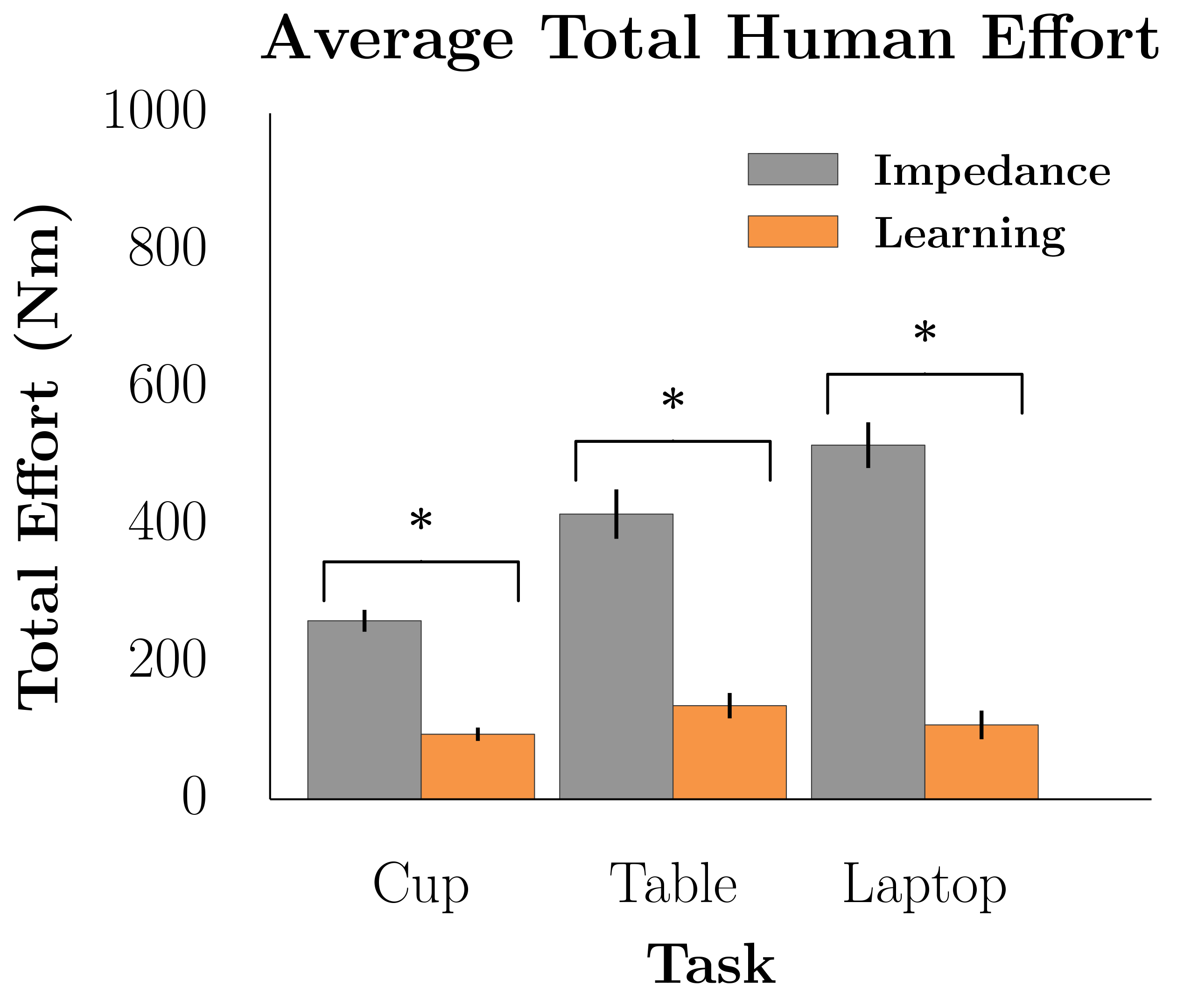

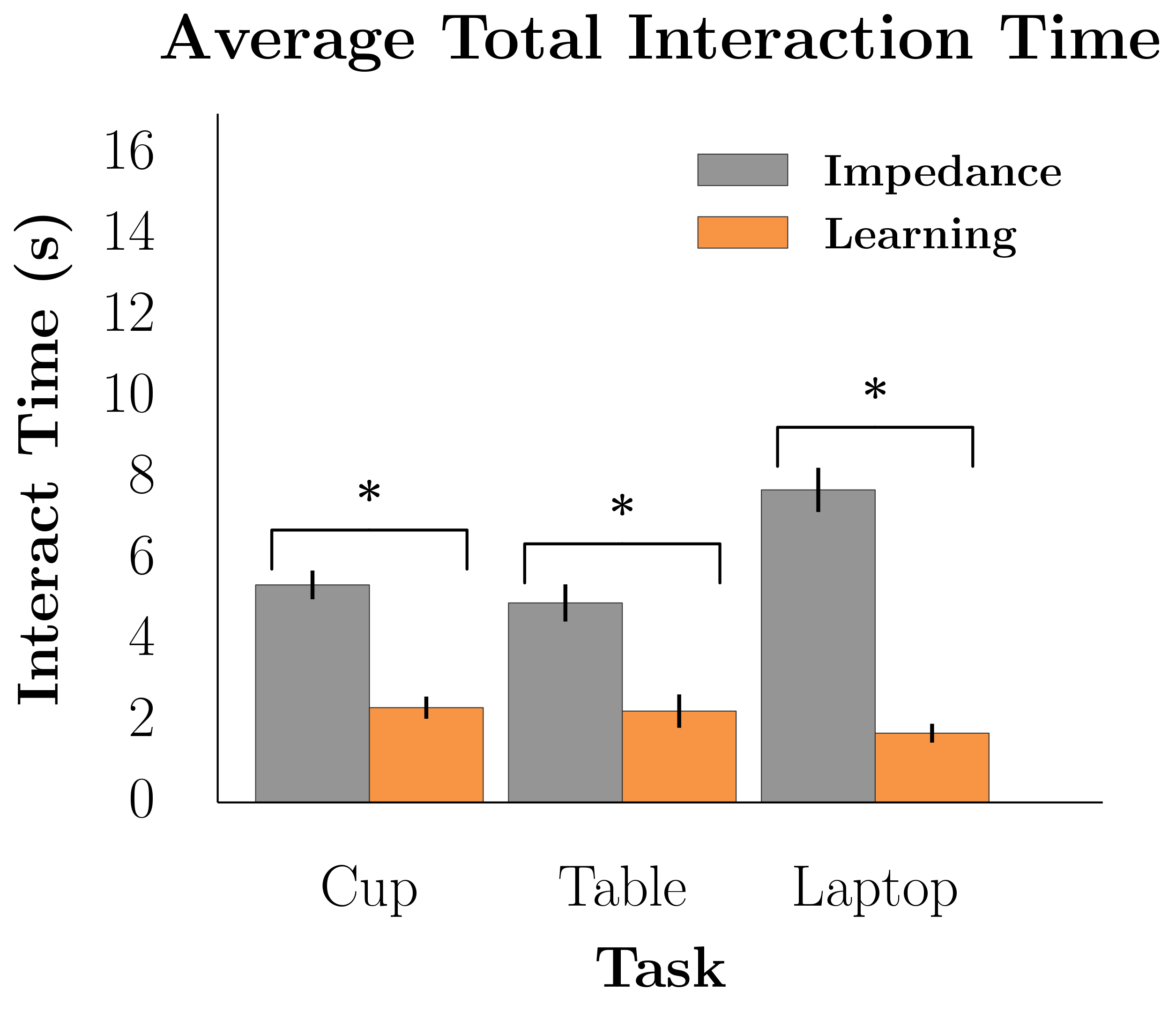

We measured the robot’s performance with respect to the true objective, the total effort the participant exerted, the total amount of interaction time, and the responses of a 7-point Likert scale survey.

In Task 1, participants have to physically intervene when they see the robot tilting the cup and teach the robot to keep the cup upright.

Task 2 had participants teaching the robot to move closer to the table.

For Task 3, the robot’s original trajectory goes over a laptop. Participants have to physically teach the robot to move around the laptop instead of over it.

The results of our user studies suggest that learning from physical interaction leads to better robot task performance with less human effort. Participants were able to get the robot to execute the correct behavior faster with less effort and interaction time when the robot was actively learning from their interactions during the task. Additionally, participants believed the robot understood their preferences more, took less effort to interact with, and was a more collaborative partner.

Fig 3. Learning from interaction significantly outperformed not learning for each of our objective measures, including task cost, human effort, interaction time.

Ultimately, we propose that robots should not treat human interactions as disturbances, but rather as informative actions. We showed that robots imbued with this sort of reasoning are capable of updating their understanding of the task they are performing and completing it correctly, rather than relying on people to guide them until the task is done.

This work is merely a step in exploring learning robot objectives from pHRI. Many open questions remain including developing solutions that can handle dynamical aspects (like preferences about the timing of the motion) and how and when to generalize learned objectives to new tasks. Additionally, robot reward functions will often have many task-related features and human interactions may only give information about a certain subset of relevant weights. Our recent work in HRI 2018 studied how a robot can disambiguate what the person is trying to correct by learning about only a single feature weight at a time. Overall, not only do we need algorithms that can learn from physical interaction with humans, but these methods must also reason about the inherent difficulties humans experience when trying to kinesthetically teach a complex – and possibly unfamiliar – robotic system.

Thank you to Dylan Losey and Anca Dragan for their helpful feedback in writing this blog post.

This post is based on the following papers:

-

A. Bajcsy* , D.P. Losey*, M.K. O’Malley, and A.D. Dragan. Learning Robot Objectives from Physical Human Robot Interaction. Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL), 2017.

-

A. Bajcsy , D.P. Losey, M.K. O’Malley, and A.D. Dragan. Learning from Physical Human Corrections, One Feature at a Time. International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), 2018.