Reinforcement Learning (RL) is a powerful technique capable of solving complex tasks such as locomotion, Atari games, racing games, and robotic manipulation tasks, all through training an agent to optimize behaviors over a reward function. There are many tasks, however, for which it is hard to design a reward function that is both easy to train and that yields the desired behavior once optimized. Suppose we want a robotic arm to learn how to place a ring onto a peg. The most natural reward function would be for an agent to receive a reward of 1 at the desired end configuration and 0 everywhere else. However, the required motion for this task–to align the ring at the top of the peg and then slide it to the bottom–is impractical to learn under such a binary reward, because the usual random exploration of our initial policy is unlikely to ever reach the goal, as seen in Video 1a. Alternatively, one can try to shape the reward function to potentially alleviate this problem, but finding a good shaping requires considerable expertise and experimentation. For example, directly minimizing the distance between the center of the ring and the bottom of the peg leads to an unsuccessful policy that smashes the ring against the peg, as in Video 1b. We propose a method to learn efficiently without modifying the reward function, by automatically generating a curriculum over start positions.

|

|

Video 1a: A randomly initialized policy is unable to reach the goal from most start positions, hence being unable to learn. |

Video 1b: Shaping the reward with a penalty on the distance from the ring center to the peg bottom yields an undesired behavior. |

Curriculum instead of Reward Shaping

We would like to train an agent to reach the goal from any starting position, without requiring an expert to shape the reward. Clearly, not all starting positions are equally difficult. In particular, even a random agent that is placed near to the goal will be able to reach the goal some of the time, receive a reward, and hence start learning! This acquired knowledge can then be bootstrapped to solve the task starting from further away from the goal. By choosing the ordering of the starting positions that we use in training, we can exploit this underlying structure of the problem and improve learning efficiency. A key advantage of this technique is that the reward function is not modified, and optimizing the sparse reward directly is less prone to yielding undesired behaviors. Ordering a set of related tasks to be learned is referred to as curriculum learning, and a central question for us is how to choose this task ordering. Our method, which we explain in more detail below, uses the performance of the learning agent to automatically generate a curriculum of tasks which start from the goal and expand outwards.

Reverse Curriculum Intuition

In goal-oriented tasks the aim is to reach a desired configuration from any start state. For example, in the ring-on-peg task introduced above, we desire to place the ring on the peg starting from any configuration. From most start positions, the random exploration of our initial policy never reaches the goal and hence perceives no reward. Nevertheless, it can be seen in Video 2a how a random policy is likely to reach the bottom of the peg if it is initialized from a nearby position. Then, once we have learned how to reach the goal from around the goal, learning from further away is easier since the agent already knows how to proceed if exploratory actions drive its state nearby the goal, as in Video 2b. Eventually, the agent successfully learns to reach the goal from a wide range of starting positions, as in Video 2c.

Video 2a-c: Our method strives to learn first starting nearby the goal, and then progressively expands in reverse the positions from where it starts.

This method of learning in reverse, or growing outwards from the goal, draws inspiration from Dynamic Programming methods, where the solutions to easier sub-problems are used to compute the solution to harder problems.

Starts of Intermediate Difficulty (SoID)

To implement this reverse curriculum, we need to ensure that this outwards expansion happens at the right pace for the learning agent. In other words, we want to mathematically describe a set of starts that tracks the current agent performance and provides a good learning signal to our Reinforcement Learning algorithm. In particular we focus on Policy Gradient algorithms, which improve a parameterized policy by taking steps in the direction of an estimated gradient of the total expected reward . This gradient estimation is usually a variation of the original REINFORCE, which is estimated by collecting $N$ on-policy trajectories \(\{\tau^i\}_{i=1..N}\) starting from states \(\{s^i_0\}_{i=1..N}\).

\[\nabla_\theta\eta=\frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^N\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(\tau^i)[R(\tau^i, s^i_0)-R(\pi_i, s^i_0)] \quad (1)\]In goal-oriented tasks, the trajectory reward $R(\tau^i, s^i_0)$ is binary, indicating whether the agent reached the goal. Therefore, the usual baseline $R(\pi_i, s^i_0)$ estimates the probability of reaching the goal if the current policy $\pi_\theta$ is executed starting from $s^i_0$. Hence, we see from Eq. (1) that the terms of the sum corresponding to trajectories collected from starts $s^i_0$ that have success probability 0 or 1 will vanish. These are “wasted” trajectories as they do not contribute to the estimation of the gradient – they are either too hard or too easy. A similar analysis was already introduced in our prior work on multi-task RL. In this case, to avoid training from starts from where our current policy either never gets to the goal or already masters it, we introduce the concept of “Start of Intermediate Difficulty” (SoID), which are start states $s_0$ that satisfy:

\[s_0:R_{min} < R(\pi_i, s_0^i) < R_{max} \quad (2)\]The values of \(R_{min}\) and \(R_{max}\) have the straightforward interpretation of minimum success probability acceptable for training from that start and maximum success probability above which we prefer to focus on training from other starts. In all our experiments we used 10% and 90%.

Automatic Generation of the Reverse Curriculum

From the above intuition and derivation, we would like to train our policy with trajectories starting from SoID states. Unfortunately, finding all starts that exactly satisfy Eq. (2) at every policy update is intractable, and hence we introduce an efficient approximation to automatically generate this reverse curriculum: we sample states nearby the starts that were estimated to be SoID during the previous iteration. To do that, we propose a way to filter out non-SoID starts using the trajectories collected during the last training iteration and then sample nearby states. The full algorithm is illustrated in Video 3 and details are given below.

Video 3: Animation illustrating the main steps of our algorithm, and how it automatically produces a curriculum adapted to the current agent performance.

Filtering out Non-SoID

At every policy gradient training iteration, we collect \(N\) trajectories from some start positions \(\{s^i_0\}_{i=1..N}\). For most start states, we collect at least three trajectories starting from there, and hence we can compute a Monte Carlo estimate of the success probability of our policy from those starts \(R_\theta(s^i_0)\). For every \(s^i_0\) that the estimate is not within the fixed bounds \(R_{min}\) and \(R_{max}\), we discard this start so that we don’t train from it during the next iteration. Starts that were SoID for a previous policy might not be SoID for the current policy because they are now mastered or because the updated policy got worse at them, so it is important to keep filtering out the non-SoID starts to maintain a curriculum adapted to the current agent performance.

Sampling Nearby

After filtering the non-SoID we need to obtain new SoIDs to keep expanding the starts from where we train. We do that by sampling states nearby the remaining SoID because those have a similar level of difficulty for the current policy – and hence might also be SoID. But what is a good way to sample nearby a certain state \(s^i_0\)? We propose to take random exploratory actions from that \(s^i_0\), and record the visited states. This technique is preferable to applying noise in state space directly because that might yield states that are not even feasible or that cannot be reached by executing actions from the original \(s^i_0\).

Assumptions

To initialize the algorithm, we need to seed it with one start at the goal \(s^g\) and then run brownian motion from it, train from the collected starts, filter out the non-SoID and iterate. This is usually easy to provide when specifying the problem, and is a milder assumption than requiring a full demonstration of how to get to that point.

Our algorithm exploits the capability of choosing the start distribution from where the collected trajectories start. This is the case in many systems, like all simulated ones. Kakade and Langford also build upon this assumption, and propose theoretical evidence of the usefulness of modifying the start distribution.

Application to Robotics

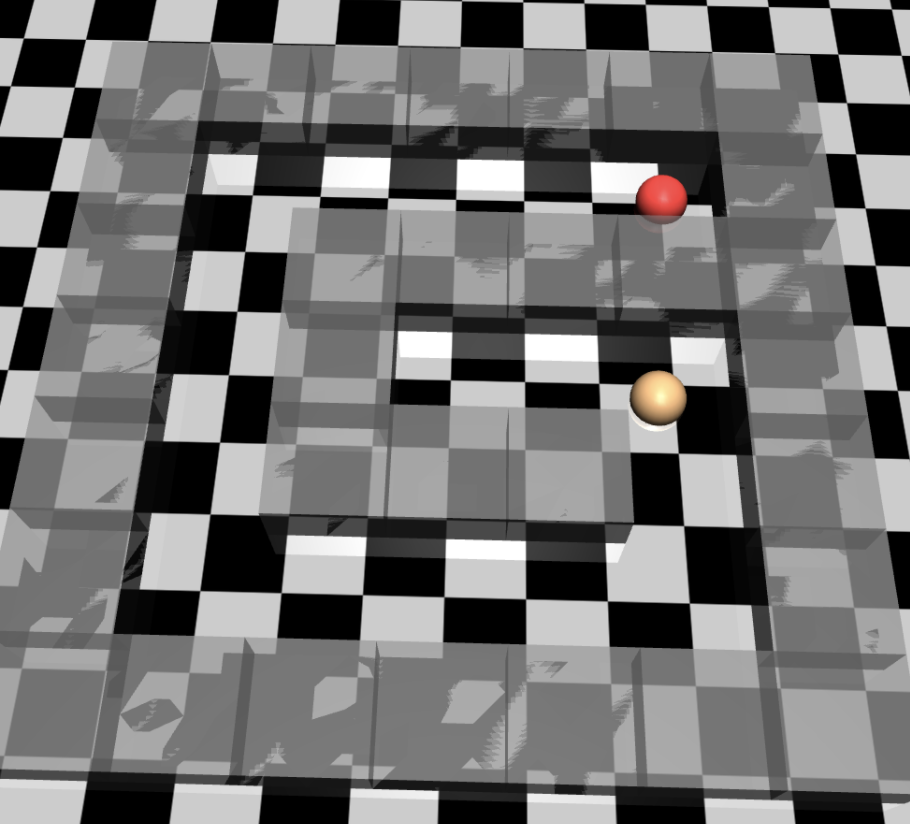

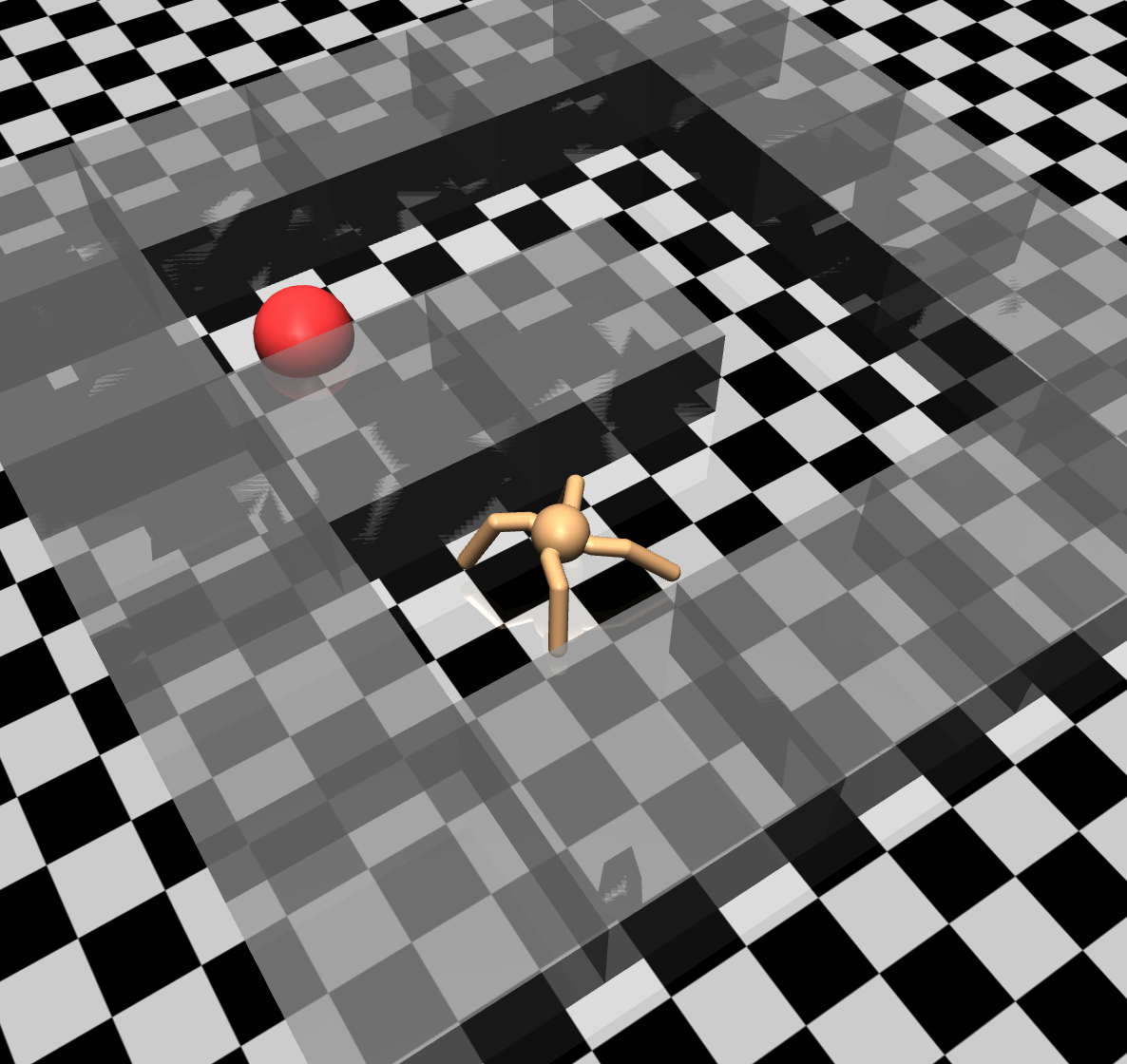

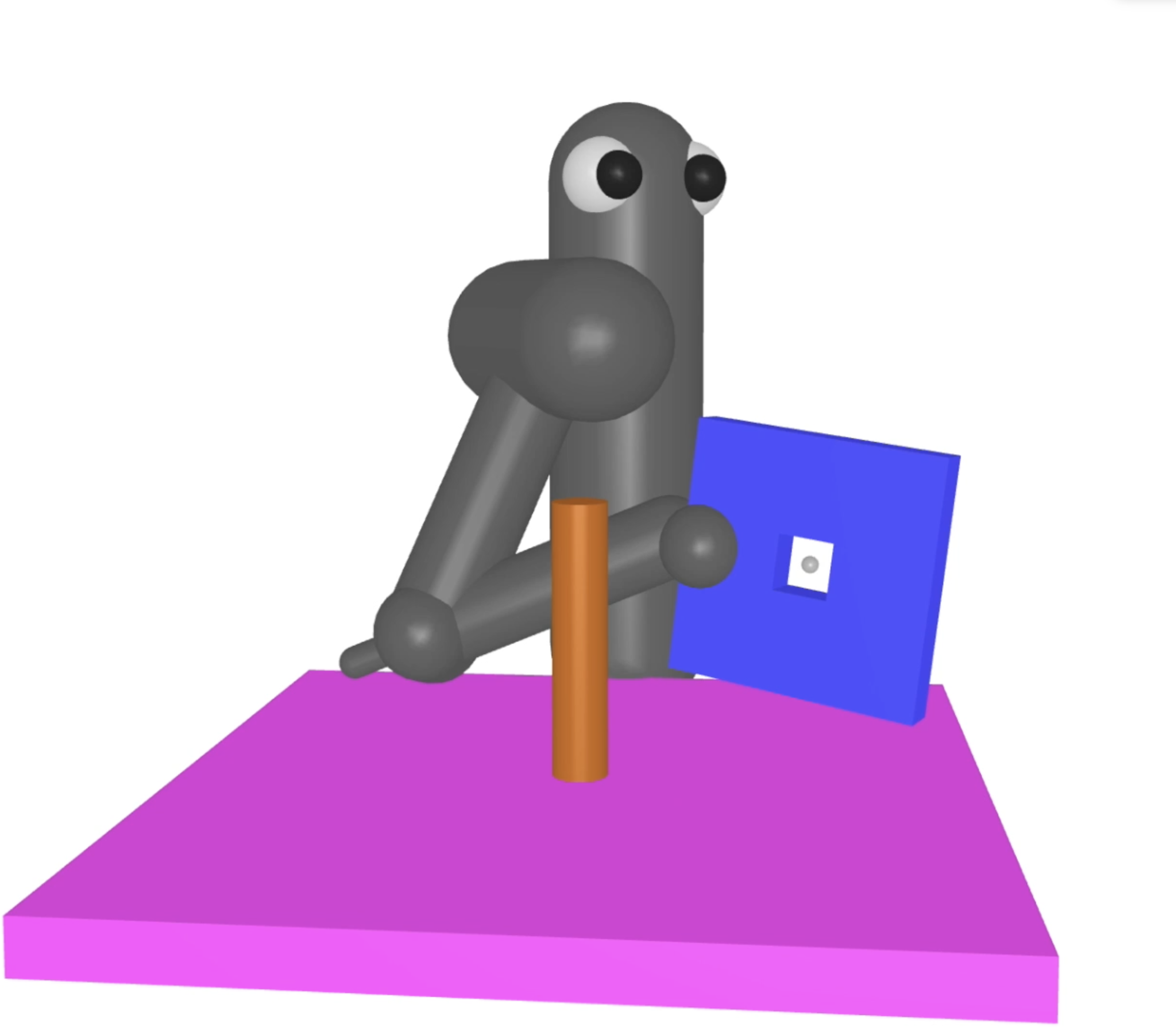

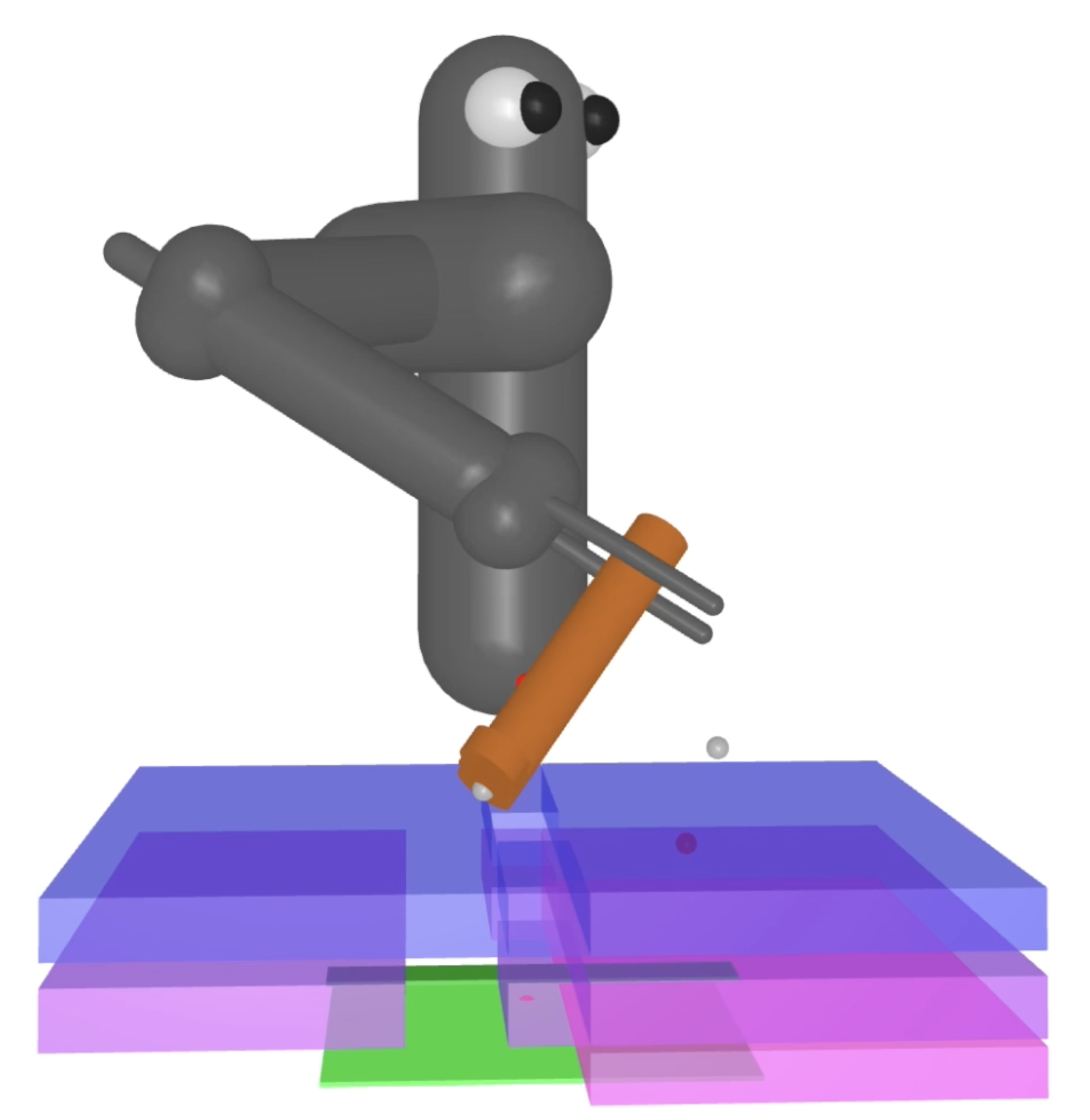

Navigation to a fixed goal and fine-grained manipulation to a desired configuration are two examples of goal-oriented robotics tasks. We analyze how the proposed algorithm automatically generates a reverse curriculum for the following tasks: Point-mass Maze (Fig. 1a), Ant Maze (Fig. 1b), Ring-on-Peg (Fig. 1c) and Key insertion (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1a-d: Tasks where we illustrate the performance of our method (from left to right): Point-mass Maze, Ant Maze, Ring-on-Peg, Key insertion.

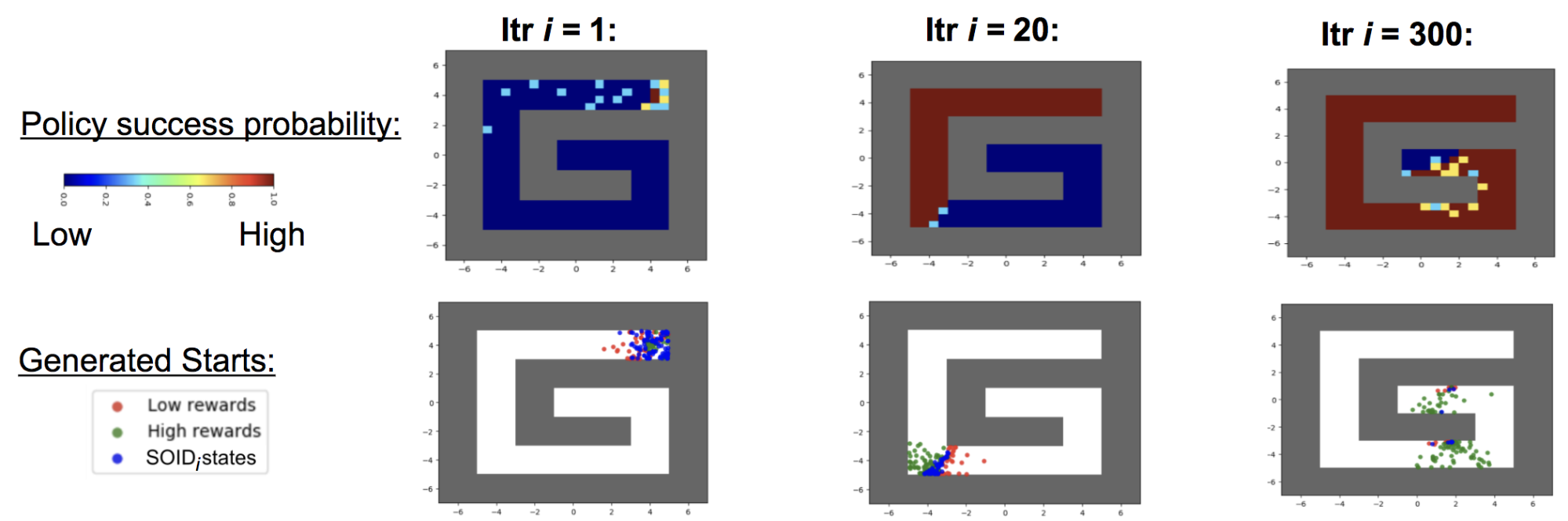

Point-mass Maze

In this task we want to learn how to reach the end of the red area in the upper-right corner of Fig. 1a from any start point within the maze. We see in Fig. 2 that a randomly initialized policy – as we have at iteration \(i=1\), has a success probability of zero from everywhere but around the goal. The second row of Fig. 2 shows how our algorithm proposes start positions nearby the goal at \(i=1\). We see in the subsequent columns that the starts generated by our method keep tracking the area where the training policy succeeds sometimes but not always, hence giving a good learning signal for any policy gradient learning method.

Fig. 2: Snapshots of the policy performance and the starts generated by our reverse curriculum (replay buffer not depicted for clarity), always tracking the regions at an intermediate level of difficulty.

To avoid forgetting how to reach the goal from some areas, we keep a replay buffer of all starts that were SoID for any previous policy. In every training iteration we sample a fraction of the trajectories starting from states in this replay.

Ant Maze Navigation

In robotics, a complex coordinated motion is often required to reach the desired configuration. For example, a quadruped like the one in Fig. 1b needs to know how to coordinate all its torques to move and advance towards the goal. As seen in a final policy reported in Video 4, our algorithm is able to learn this behavior even when only a success/failure reward is provided when reaching the goal! The reward function was not modified to include any distance-to-goal, Center of Mass speed, or exploration bonus.

Video 4: Emergence of complex coordination and use of environment contacts when training with our reverse curriculum method - even under sparse rewards.

Fine-grained Manipulation

Our method can also tackle complex robotic manipulation problems like the ones depicted in Fig. 1c and 1d. Both task have a seven Degrees of Freedom arm and have complex contact constraints. The first task requires the robot to insert a ring down to the bottom of the peg, and the second task seeks to insert a key in a lock, rotate 90 degrees clockwise, insert it further and rotate 90 degrees counterclockwise. In both cases, a reward is only granted when the desired end configuration is reached. State-of-the-art RL algorithms without curriculum are unable to learn how to solve the task, but with our reverse curriculum generation we can obtain a successful policy from a wide range of start positions, as observed in Videos 5a and 5b.

Video 5a (left) and Video 5b (right): Final policies obtained with our reverse curriculum approach in the Ring-on-Peg and the Key Insertion tasks. The agent succeeds from a wide range of initial positions and is able to leverage the contacts to guide itself.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Recently RL methods have been moving away from the single-task paradigm to tackle sets of tasks. This is an effort to get closer to real-world scenarios, where every time a tasks needs to be executed there are always variations in the starting configuration, goal or other parameters. Therefore it is of utmost importance to advance the field of curriculum learning to exploit the underlying structure of these sets of tasks. Our Reverse Curriculum strategy is a step in this direction, yielding impressive results in locomotion and complex manipulation tasks that cannot be solved without a curriculum.

Furthermore, it can be observed in the videos of our final policy for the manipulation tasks that the agent has learned to exploit the contacts in the environment instead of avoiding them. Therefore, the learning based aspect of the presented method has a great potential to tackle problems that classical motion planning algorithms could struggle with, such as environments with non-rigid objects or with uncertainties in the task geometric parameters. We also leave as future work to combine our curriculum-generation approach with domain randomization methods to obtain policies that are transferable to the real world.

If you want to learn more, check out our paper published in the Conference on Robot Learning:

Carlos Florensa, David Held, Markus Wulfmeier, Michael Zhang, Pieter Abbeel. Reverse Curriculum Generation for Reinforcement Learning. In CoRL 2017.

We have also open-sourced the code in the project website.

We would like to thank the co-authors of this work, who also provided very valuable feedback for this blog post: David Held, Markus Wulfmeier, Michael R. Zhang and Pieter Abbeel.

Further Readings:

A. Graves, M. G. Bellemare, J. Menick, R. Munos, and K. Kavukcuoglu. Automated Curriculum Learning for Neural Networks. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1704.03003, 2017.

M. Asada, S. Noda, S. Tawaratsumida, and K. Hosoda. Purposive behavior acquisition for a real robot by Vision-Based reinforcement learning. Machine Learning, 1996.

A. Karpathy and M. Van De Panne. Curriculum learning for motor skills. In Canadian Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 325–330. Springer, 2012.

J. Schmidhuber. POWER PLAY : Training an Increasingly General Problem Solver by Continually Searching for the Simplest Still Unsolvable Problem. Frontiers in Psychology, 2013.

A. Baranes and P.-Y. Oudeyer. Active learning of inverse models with intrinsically motivated goal exploration in robots. Robotics and Autonomous Systems, 61(1), 2013.

S. Sharma and B. Ravindran. Online Multi-Task Learning Using Biased Sampling. arXiv preprint arXiv: 1702.06053, 2017. 9

S. Sukhbaatar, I. Kostrikov, A. Szlam, and R. Fergus. Intrinsic Motivation and Automatic Curricula via Asymmetric Self-Play. arXiv preprint, arXiv: 1703.05407, 2017.

J. A. Bagnell, S. Kakade, A. Y. Ng, and J. Schneider. Policy search by dynamic programming. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 16:79, 2003.

S. Kakade and J. Langford. Approximately Optimal Approximate Reinforcement Learning. International Conference in Machine Learning, 2002.