Deep reinforcement learning (deep RL) has achieved success in many tasks, such as playing video games from raw pixels (Mnih et al., 2015), playing the game of Go (Silver et al., 2016), and simulated robotic locomotion (e.g. Schulman et al., 2015). Standard deep RL algorithms aim to master a single way to solve a given task, typically the first way that seems to work well. Therefore, training is sensitive to randomness in the environment, initialization of the policy, and the algorithm implementation. This phenomenon is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows two policies trained to optimize a reward function that encourages forward motion: while both policies have converged to a high-performing gait, these gaits are substantially different from each other.

Figure 1: Trained simulated walking robots.

[credit: John Schulman and Patrick Coady (OpenAI Gym)]

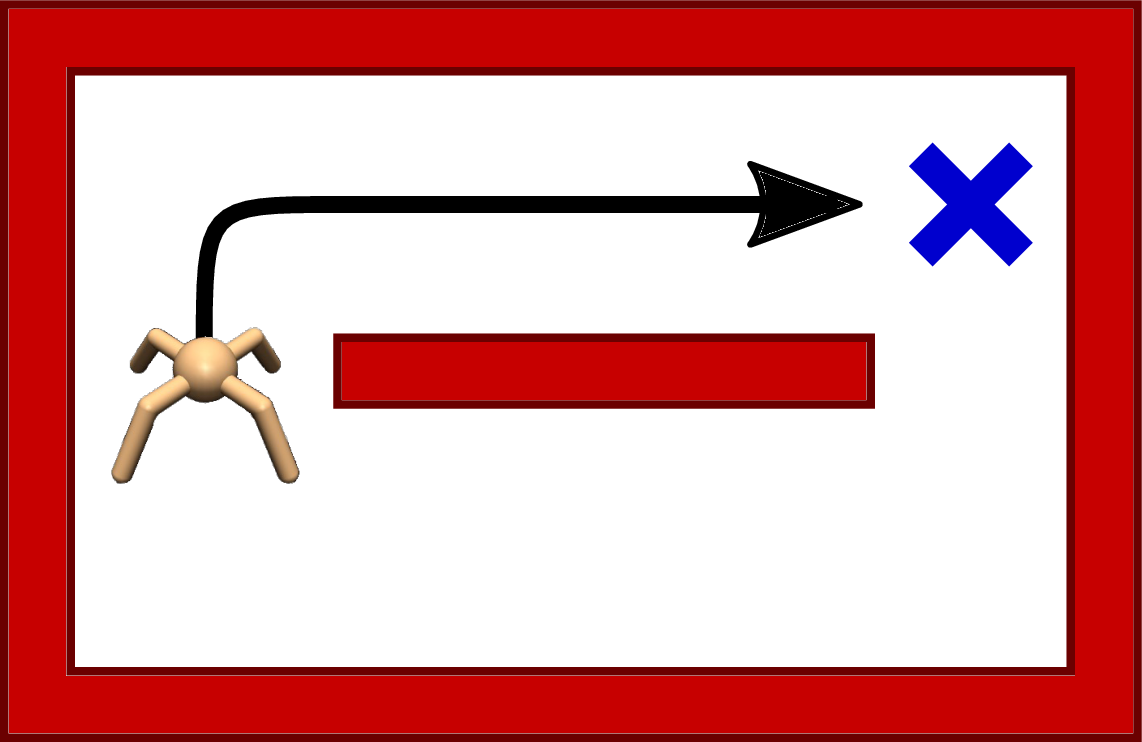

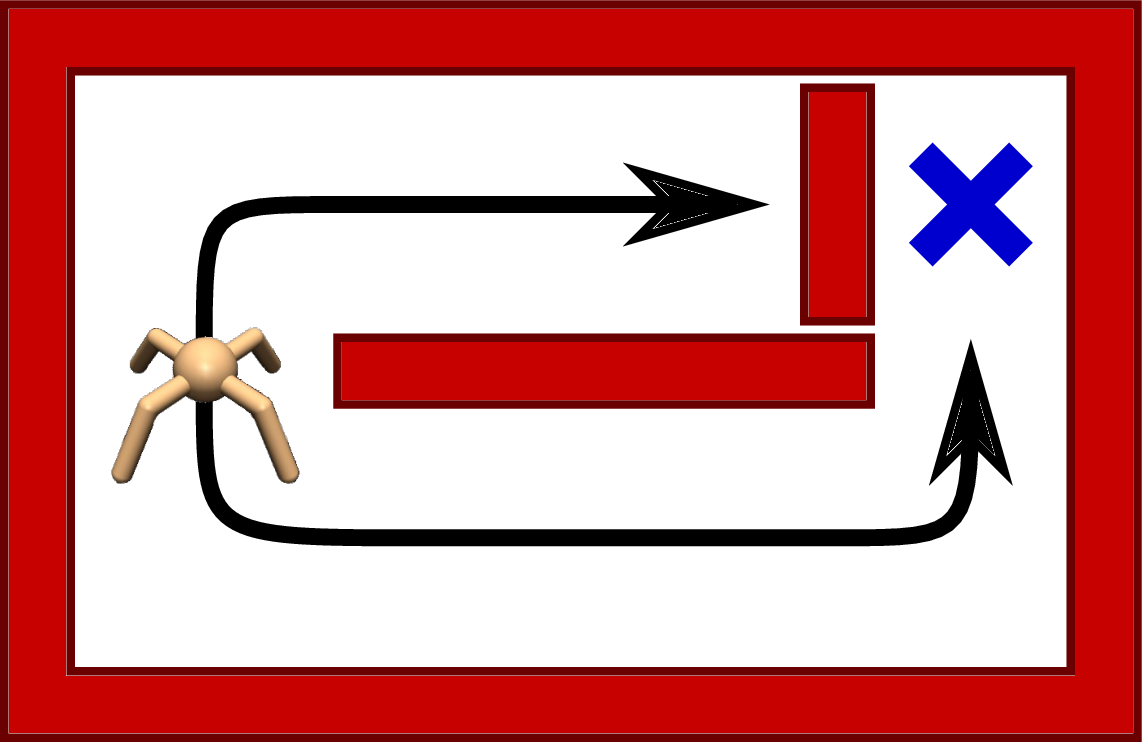

Why might finding only a single solution be undesirable? Knowing only one way to act makes agents vulnerable to environmental changes that are common in the real-world. For example, consider a robot (Figure 2) navigating its way to the goal (blue cross) in a simple maze. At training time (Figure 2a), there are two passages that lead to the goal. The agent will likely commit to the solution via the upper passage as it is slightly shorter. However, if we change the environment by blocking the upper passage with a wall (Figure 2b), the solution the agent has found becomes infeasible. Since the agent focused entirely on the upper passage during learning, it has almost no knowledge of the lower passage. Therefore, adapting to the new situation in Figure 2b requires the agent to relearn the entire task from scratch.

2a |

2b |

Figure 2: A robot navigating a maze.

Maximum Entropy Policies and Their Energy Forms

Let us begin with a review of RL: an agent interacts with an environment by iteratively observing the current state ($\mathbf{s}$), taking an action ($\mathbf{a}$), and receiving a reward ($r$). It employs a (stochastic) policy ($\pi$) to select actions, and finds the best policy that maximizes the cumulative reward it collects throughout an episode of length $T$:

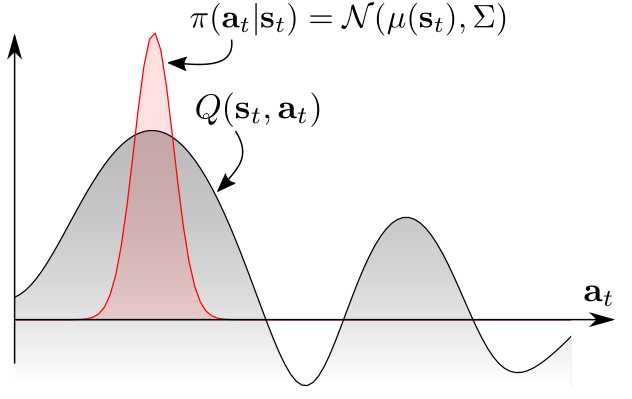

\[\pi^* = \arg\!\max_{\pi} \mathbb{E}_{\pi}\left[ \sum_{t=0}^T r_t \right]\]We define the Q-function, $Q(\mathbf{s},\mathbf{a})$, as the expected cumulative reward after taking action a at state s. Consider the robot in Figure 2a again. When the robot is in the initial state, the Q-function may look like the one depicted in Figure 3a (grey curve), with two distinct modes corresponding to the two passages. A conventional RL approach is to specify a unimodal policy distribution, centered at the maximal Q-value and extending to the neighbouring actions to provide noise for exploration (red distribution). Since the exploration is biased towards the upper passage, the agent refines its policy there and ignores the lower passage completely.

3a |

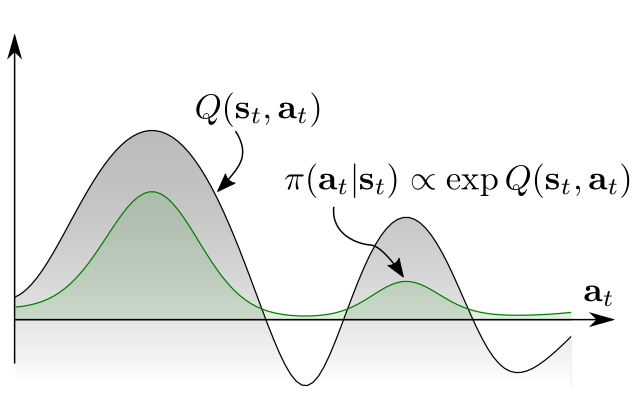

3b |

Figure 3: A multimodal Q-function.

An obvious solution, at the high level, is to ensure the agent explores all promising states while prioritizing the more promising ones. One way to formalize this idea is to define the policy directly in terms of exponentiated Q-values (Figure 3b, green distribution):

\[\pi(\mathbf{a}|\mathbf{s}) \propto \exp Q(\mathbf{s}, \mathbf{a})\]This density has the form of the Boltzmann distribution, where the Q-function serves as the negative energy, which assigns a non-zero likelihood to all actions. As a consequence, the agent will become aware of all behaviours that lead to solving the task, which can help the agent adapt to changing situations in which some of the solutions might have become infeasible. In fact, we can show that the policy defined through the energy form is an optimal solution for the maximum-entropy RL objective

\[\pi_{\mathrm{MaxEnt}}^* = \arg\!\max_{\pi} \mathbb{E}_{\pi}\left[ \sum_{t=0}^T r_t + \mathcal{H}(\pi(\cdot | \mathbf{s}_t)) \right]\]which simply augments the conventional RL objective with the entropy of the policy (Ziebart 2010).

The idea of learning such maximum entropy models has its origin in statistical modeling, in which the goal is to find the probability distribution that has the highest entropy while still satisfying the observed statistics. For example, if the distribution is on the Euclidean space and the observed statistics are the mean and the covariance, then the maximum entropy distribution is a Gaussian with the corresponding mean and covariance. In practice, we prefer maximum-entropy models as they assume the least about the unknowns while matching the observed information.

A number of prior works have employed the maximum-entropy principle in the context of reinforcement learning and optimal control. Ziebart (2008) used the maximum entropy principle to resolve ambiguities in inverse reinforcement learning, where several reward functions can explain the observed demonstrations. Several works (Todorov 2008; Toussaint, 2009]) have studied the connection between inference and control via the maximum entropy formulation. Todorov (2007, 2009) also showed how the maximum entropy principle can be employed to make MDPs linearly solvable, and Fox et al. (2016) utilized the principle as a means to incorporate prior knowledge into a reinforcement learning policy.

Soft Bellman Equation and Soft Q-Learning

We can obtain the optimal solution of the maximum entropy objective by employing the soft Bellman equation

\[Q(\mathbf{s}_t, \mathbf{a}_t) = \mathbb{E}\left[r_t + \gamma\ \mathrm{softmax}_{\mathbf{a}} Q(\mathbf{s}_{t+1}, \mathbf{a})\right]\]where

\[\mathrm{softmax}_{\mathbf{a}} f(\mathbf{a}) := \log \int \exp f(\mathbf{a}) \, d\mathbf{a}\]The soft Bellman equation can be shown to hold for the optimal Q-function of the entropy augmented reward function (e.g. Ziebart 2010). Note the similarity to the conventional Bellman equation, which instead has the hard max of the Q-function over the actions instead of the softmax. Like the hard version, the soft Bellman equation is a contraction, which allows solving for the Q-function using dynamic programming or model-free TD learning in tabular state and action spaces (e.g. Ziebart, 2008; Rawlik, 2012; Fox, 2016).

However, in continuous domains, there are two major challenges. First, exact dynamic programming is infeasible, since the soft Bellman equation needs to hold for every state and action, and the softmax involves integrating over the entire action space. Second, the optimal policy is defined by an intractable energy-based distribution, which is difficult to sample from. To address the first challenge, we can employ expressive neural network function approximators, which can be trained with stochastic gradient descent on sampled states and actions and then generalize effectively to new state-action tuples. To address the second challenge, we can employ approximate inference techniques, such as Markov chain Monte Carlo, which has been explored in prior works for energy-based policies (Heess, 2012). To accelerate inference, we use the amortized Stein variational gradient descent (Wang and Liu, 2016) to train an inference network to generate approximate samples. The resulting algorithm, termed soft Q-learning, combines deep Q-learning and the amortized Stein variational gradient descent.

Application to Reinforcement Learning

Now that we can learn maximum entropy policies via soft Q-learning, we might wonder: what are the practical uses of this approach? In the following sections, we illustrate with experiments that soft Q-learning allows for better exploration, enables policy transfer between similar tasks, allows new policies to be easily composed from existing policies, and improves robustness through extensive exploration at training time.

Better Exploration

Soft Q-learning (SQL) provides us with an implicit exploration strategy by assigning each action a non-zero probability, shaped by the current belief about its value, effectively combining exploration and exploitation in a natural way. To see this, let us consider a two-passage maze (Figure 4) similar to the one discussed in the introduction. The task is to find a way to the goal state, denoted by a blue square. Suppose that the reward is proportional to the distance to the goal. Since the maze is almost symmetric, such a reward results in a bimodal objective, but only one of the modes corresponds to an actual solution to the task. Thus, exploring both passages at training time is crucial to discover which of the two is really best. A unimodal policy can only solve this task if it is lucky enough to commit to the lower passage from the start. On the other hand, a multimodal soft Q-learning policy can solve the task consistently by following both passages randomly until the agent finds the goal (Figure 4).

Figure 4: A policy trained with soft Q-learning can explore both passages during training.

Fine-Tuning Maximum Entropy Policies

The standard practice in RL is to train an agent from scratch for each new task. This can be slow because the agent throws away knowledge acquired from previous tasks. Instead, the agent can transfer skills from similar previous tasks, allowing it to learn new tasks more quickly. One way to transfer skills is to pre-train policies for general purpose tasks, and then use them as templates or initializations for more specific tasks. For example, the skill of walking subsumes the skill of navigating through a maze, and therefore the walking skill can serve as an efficient initialization for learning the navigation skill. To illustrate this idea, we trained a maximum entropy policy by rewarding the agent for walking at a high speed, regardless of the direction. The resulting policy learns to walk, but does not commit to any single direction due to the maximum entropy objective (Figure 5a). Next, we specialized the walking skill to a range of navigation skills, such as the one in Figure 5b. In the new task, the agent only needs to choose which walking behavior will move itself closer to the goal, which is substantially easier than learning the same skill from scratch. A conventional policy would converge to a specific behaviour when trained for the general task. For example, it may only learn to walk in a single direction. Consequently, it cannot directly transfer the walking skill to the maze environment, which requires movement in multiple directions.

5a |

5b |

Figure 5: Maximum entropy pretraining allows agents to learn more quickly in new environments. Videos of the same pretrained policy fine-tuned for other target tasks can be found at this link.

Compositionality

In a similar vein to general-to-specific transfer, we can compose new skills from existing policies—even without any fine-tuning—by intersecting different skills. The idea is simple: take two soft policies, each corresponding to a different set of behaviors, and combine them by adding together their Q-functions. In fact, it is possible to show that the combined policy is approximately optimal for the combined task, obtained by simply adding the reward functions of the constituent tasks, up to a bounded error. Consider a planar manipulator as the one pictured below. The two agents on the left are trained to move the cylindrical object to a target location illustrated with red stripes. Note, how the solution space of the two tasks overlap: by moving the cylinder to the intersection of the stripes, both tasks can be solved simultaneously. Indeed, the policy on the right, which is obtained by simply summing together the two Q-functions, moves the cylinder to the intersection, without the need to train a policy explicitly for the combined task. Conventional policies do not exhibit the same compositionality property as they can only represent specific, disjoint solutions.

Figure 6: Combining two skills into a new one.

Robustness

Because the maximum entropy formulation encourages agents to try all possible solutions, the agents learn to explore a large portion of the state space. Thus they learn to act in various situations, and are more robust against perturbations in the environment. To illustrate this, we trained a Sawyer robot to stack Lego blocks together by specifying a target end-effector pose. Figure 7 shows some snapshots during training.

Figure 7: Training to stack Lego blocks with soft Q-learning.

[credit: Aurick Zhou]

The robot succeeded for the first time after 30 minutes; after an hour, it was able to stack the blocks consistently; and after two hours, the policy had fully converged. The converged policy is also robust to perturbations as shown in the video below, in which the arm is perturbed into configurations that are very different from what it encounters during normal execution, and it is able to successfully recover every time.

Figure 8: The trained policy is robust to perturbations.

Related Work

Soft optimality has also been studied in recent papers in the context of learning from multi-step transitions (Nachum et al., 2017) and its connection to policy gradient methods (Schulman et al., 2017). A related concept is discussed by O’Donoghue et al. (2016), who also consider entropy regularization and Boltzmann exploration. This version of entropy regularization only considers the entropy of the current state, and does not take into account the entropy for the future states.

To our knowledge, only a few prior works have demonstrated successful model-free reinforcement learning directly on real-world robots. Gu et al. (2016) showed that NAF could learn door opening tasks, using about 2.5 hours of experience parallelized across two robots. Rusu et al. (2016) used RL to train a robot arm to reach a red square, with pretraining in simulation. Večerı́k et al. (2017) showed that, if initialized from demonstration, a Sawyer robot could perform a peg-insertion style task with about 30 minutes of experience. It is worth noting that our soft Q-learning results, shown above, used only a single robot for training, and did not use any simulation or demonstrations.

We would like to thank Sergey Levine, Pieter Abbeel, and Gregory Kahn for their valuable feedback when preparing this blog post.

This post is based on the following paper:

Reinforcement Learning with Deep Energy-Based Policies

Haarnoja T., Tang H., Abbeel P., Levine S. ICML 2017.

paper, code, videos

References

Related concurrent papers

- Schulman, J., Abbeel, P. and Chen, X. Equivalence Between Policy Gradients and Soft Q-Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.06440, 2017.

- Nachum, O., Norouzi, M., Xu, K. and Schuurmans, D. Bridging the Gap Between Value and Policy Based Reinforcement Learning. NIPS 2017.

Papers leveraging the maximum entropy principle

- Kappen, H. J. Path integrals and symmetry breaking for optimal control theory. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory And Experiment, 2005(11): P11011, 2005.

- Todorov, E. Linearly-solvable Markov decision problems. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pp. 1369–1376. MIT Press, 2007.

- Todorov, E. General duality between optimal control and estimation. In IEEE Conf. on Decision and Control, pp. 4286–4292. IEEE, 2008.

- Todorov, E. (2009). Compositionality of optimal control laws. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 1856-1864).

- Ziebart, B. D., Maas, A. L., Bagnell, J. A., and Dey, A. K. Maximum entropy inverse reinforcement learning. In AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pp. 1433–1438, 2008.

- Toussaint, M. Robot trajectory optimization using approximate inference. In Int. Conf. on Machine Learning, pp. 1049–1056. ACM, 2009.

- Ziebart, B. D. Modeling purposeful adaptive behavior with the principle of maximum causal entropy. PhD thesis, 2010.

- Rawlik, K., Toussaint, M., and Vijayakumar, S. On stochastic optimal control and reinforcement learning by approximate inference. Proceedings of Robotics: Science and Systems VIII, 2012.

- Fox, R., Pakman, A., and Tishby, N. Taming the noise in reinforcement learning via soft updates. In Conf. on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence, 2016.

Model-free RL in the real-world

- Gu, S., Lillicrap, T., Sutskever, I., and Levine, S. Continuous deep Q-learning with model-based acceleration. In Int. Conf. on Machine Learning, pp. 2829–2838, 2016.

- M. Večerı́k, T. Hester, J. Scholz, F. Wang, O. Pietquin, B. Piot, N. Heess, T. Rothörl, T. Lampe, and M. Riedmiller, “Leveraging demonstrations for deep reinforcement learning on robotics problems with sparse rewards,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.08817, 2017.

Other references

Heess, N., Silver, D., and Teh, Y.W. Actor-critic reinforcement learning with energy-based policies. In Workshop on Reinforcement Learning, pp. 43. Citeseer, 2012.

Jaynes, E.T. Prior probabilities. IEEE Transactions on systems science and cybernetics, 4(3), pp.227-241, 1968.

Lillicrap, T. P., Hunt, J. J., Pritzel, A., Heess, N., Erez, T., Tassa, Y., Silver, D., and Wierstra, D. Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning. ICLR 2016.

Liu, Q. and Wang, D. Stein variational gradient descent: A general purpose bayesian inference algorithm. In Advances In Neural Information Processing Systems, pp. 2370–2378, 2016.

Mnih, V., Kavukcuoglu, K., Silver, D., Rusu, A. A, Veness, J., Bellemare, M. G., Graves, A., Riedmiller, M., Fidjeland, A. K., Ostrovski, G., et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature, 518 (7540):529–533, 2015.

Mnih, V., Badia, A.P., Mirza, M., Graves, A., Lillicrap, T., Harley, T., Silver, D. and Kavukcuoglu, K. Asynchronous methods for deep reinforcement learning. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 1928-1937), 2016.

O’Donoghue, B., Munos, R., Kavukcuoglu, K., and Mnih, V. PGQ: Combining policy gradient and Q-learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1611.01626, 2016.

Rusu, A. A., Vecerik, M., Rothörl, T., Heess, N., Pascanu, R. and Hadsell, R., Sim-to-real robot learning from pixels with progressive nets. arXiv preprint arXiv:1610.04286, 2016.

Schulman, J., Levine, S., Abbeel, P., Jordan, M., & Moritz, P. Trust region policy optimization. Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-15), 2015.

Silver, D., Huang, A., Maddison, C.J., Guez, A., Sifre, L., Van Den Driessche, G., Schrittwieser, J., Antonoglou, I., Panneershelvam, V., Lanctot, M. and Dieleman, S. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature, 529(7587), 484-489, 2016.

Sutton, R. S. and Barto, A. G. Reinforcement learning: An introduction, volume 1. MIT press Cambridge, 1998.

Tobin, J., Fong, R., Ray, A., Schneider, J., Zaremba, W. and Abbeel, P. Domain Randomization for Transferring Deep Neural Networks from Simulation to the Real World. arXiv preprint arXiv:1703.06907, 2017.

Wang, D., and Liu, Q. Learning to draw samples: With application to amortized MLE for generative adversarial learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1611.01722, 2016.