Why we need Attention

What we see through our eyes is only a very small part of the world around us. At any given time our eyes are sampling only a fraction of the surrounding light field. Even within this fraction, most of the resolution is dedicated to the center of gaze which has the highest concentration of ganglion cells. These cells are responsible for conveying a retinal image from our eyes to our brain. Unlike a camera, the spatial distribution of ganglion cells is highly non-uniform. As a result, our brain receives a foveated image:

|

|

A foveated image with a center of gaze on the bee (left) and butterfly (right) (source).

Despite the fact that these cells cover only a fraction of our visual field, roughly 30% of our cortex is still dedicated to processing the signal that they provide. You can imagine our brain would have to be impractically large to handle the full visual field at high resolution. Suffice it to say, the amount of neural processing dedicated to vision is rather large and it would be beneficial to survival if it were used efficiently.

Attention is a fundamental property of many intelligent systems. Since the resources of any physical system are limited, it is important to allocate them in an effective manner. Attention involves the dynamic allocation of information processing resources to best accomplish a specific task. In nature, we find this very apparent in the design of animal visual systems. By moving gaze rapidly within the scene, limited neural resources are effectively spread over the entire visual scene.

Overt Attention

In this work, we study overt attention mechanisms which involve the explicit movement of the sensory organ. An example of this form of attention can be seen in the adolescent jumping spider:

An adolescent jumping spider using overt attention.

We can see the spider is attending to different parts of its environment by making careful, deliberate movements of its body. When peering through its translucent head, you can even see the spider moving its eye stalks in a similar manner to how humans move their own eyes. These eye movements are called saccades.

In this work, we build a model visual system that must make saccades over a scene in order to find and recognize an object. This model allows us to study the properties of an attentional system by exploring the design parameters that optimize performance. One parameter of interest in visual neuroscience is the retinal sampling lattice which defines the relative positions of the array of ganglion cells in our eyes.

|

|

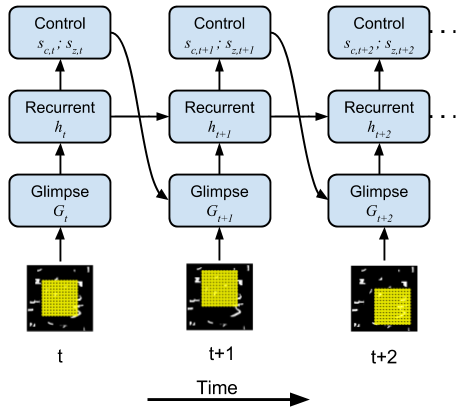

(Left) Our model retinal sampling lattice attending to different parts of a simple scene. (Right) Our neural network model which controls the window of attention.

Approximating Evolution through Gradient Descent

Evolutionary pressure has presumably tuned the retinal sampling lattice in the primate retina to be optimal for visual search tasks faced by the animal. In lieu of simulating evolution, we utilize a more efficient stochastic gradient descent procedure for our in-silico model by constructing a fully differentiable dynamic model of attention.

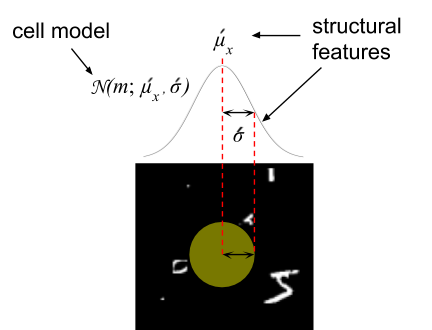

Most neural networks are composed of learnable feature extractors which transform a fixed input to a more abstract representation such as a category. While the internal features (i.e. weight matrices and kernel filters) are learned during training, the geometry of the input remains fixed. We extend the deep learning framework to create learnable structural features. We learn the geometry of the neural sampling lattice in the retina.

Structural features of one cell in the lattice.

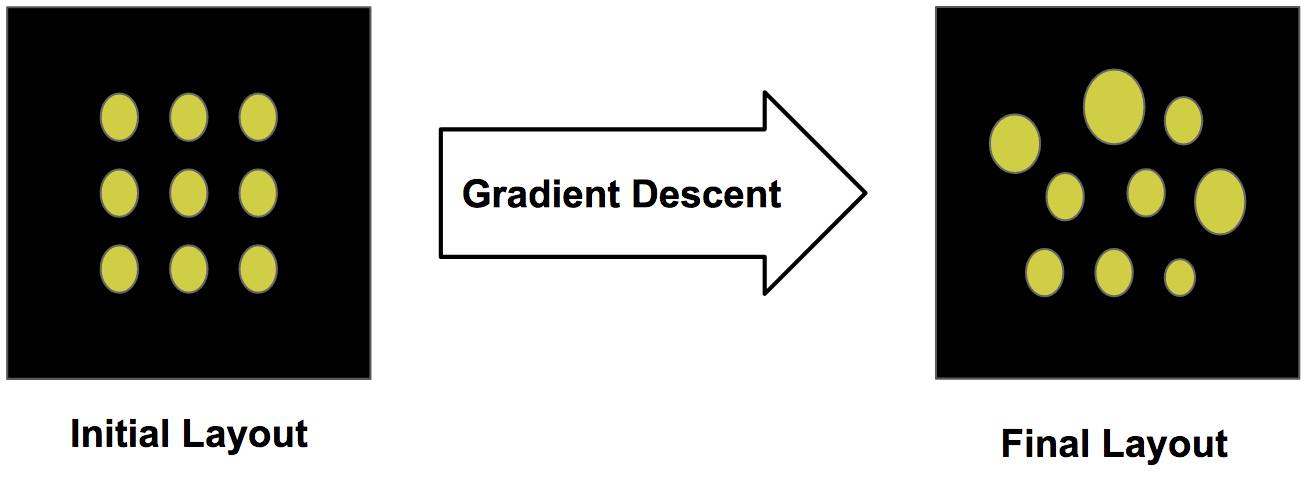

The retinal sampling lattice of our model is learned via backpropagation. Similar to the way weights are adjusted in a neural network, we adjust the parameters of the retinal tiling to optimize a loss function. We initialize the retinal sampling lattice to a regular square grid and update the parameterization of this layout using gradient descent.

Learning structural features from initialization using gradient descent.

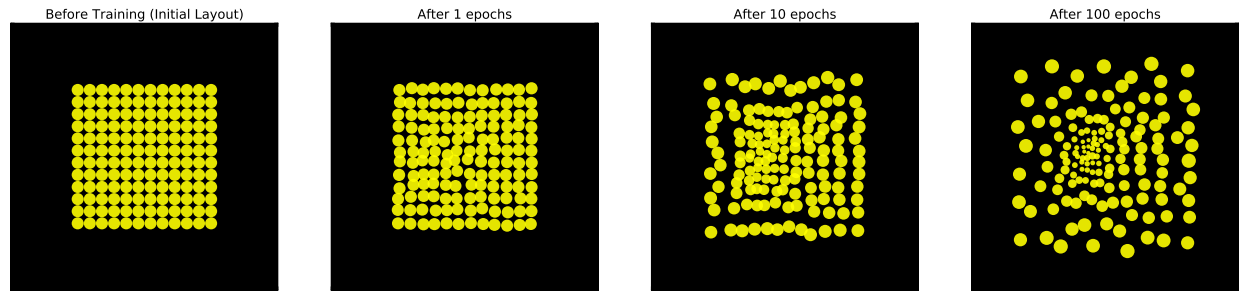

Over time, this layout will converge to a configuration which is locally optimal to minimize the task loss. In our case, we classify of the MNIST digit in a larger visual scene. Below we see how the retinal layout changes during training:

Retinal sampling lattice during training at initialization, 1, 10, 100 epochs respectively.

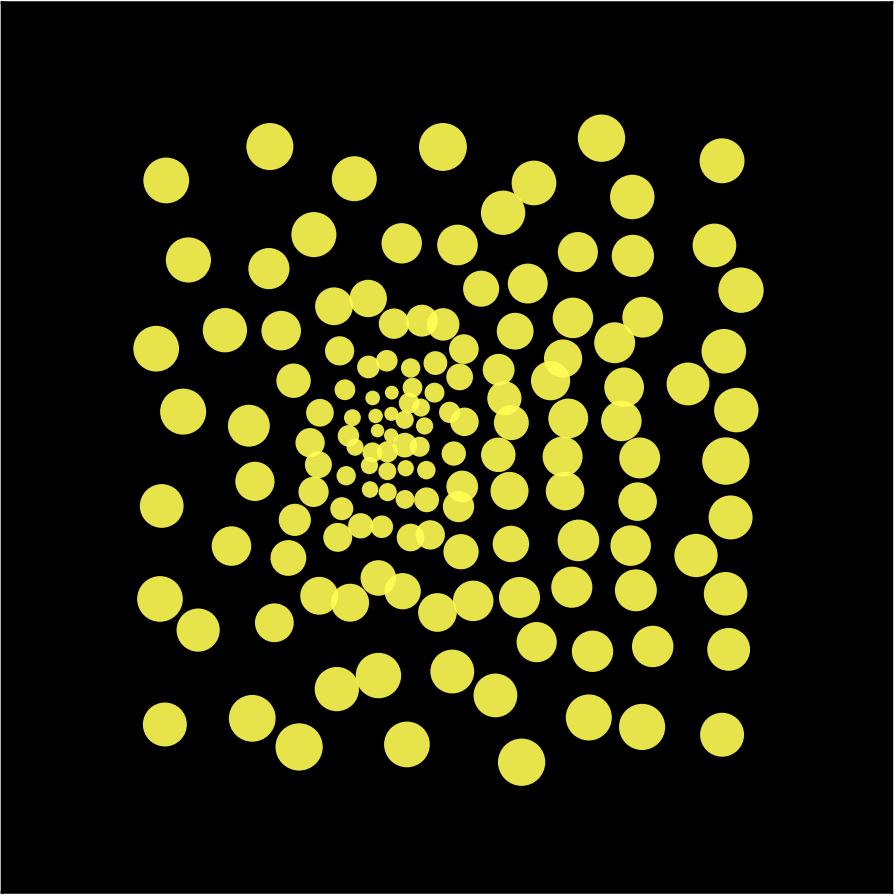

Surprisingly, the cells change in a very structured manner, smoothly transforming from a uniform grid to an eccentricity dependent lattice. We notice a concentration of high acuity cells appear near the center of the sampling array. Furthermore, the cells spread their individual centers to create a sampling lattice which covers the full image.

Controlling the Emergence of a Fovea

Since our model is in-silico, we can endow our model with properties not found in nature to see what other layouts will emerge. For example, we can give our model the ability to zoom in and out of an image by rescaling the entire grid to cover a smaller or larger area:

Retinal sampling lattice which also has the ability to rescale itself.

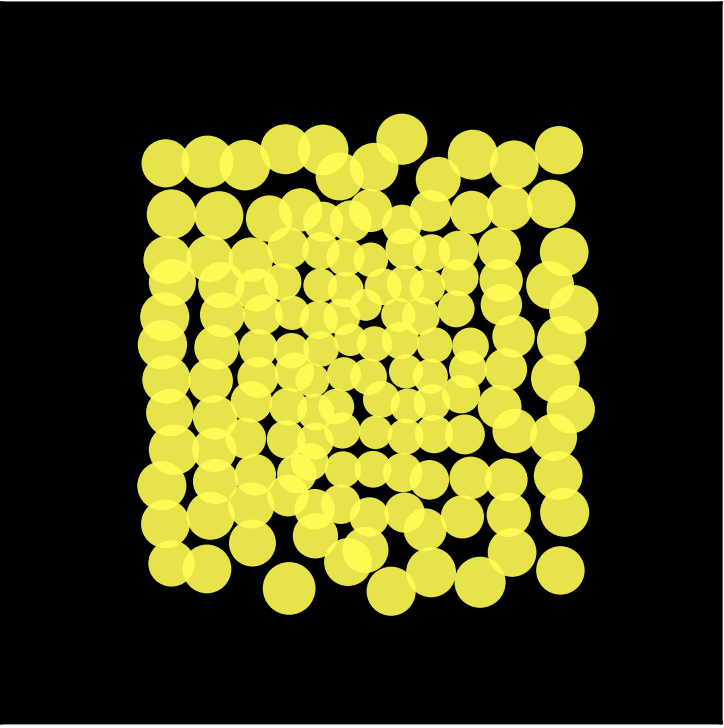

We show the difference in the learned retinal layout below. For comparison, the left image is the retinal layout when our model does not have the ability to zoom while the right image is the layout learned when zooming is possible.

|

|

(Left) Retinal lattice of a model only able to translate. (Right) Retinal lattice of a model able to translate and zoom.

When our attention model is able to zoom, a very different layout emerges. Notice there is much less diversity in the retinal ganglion cells. They cells keep many of the properties they were initialized with.

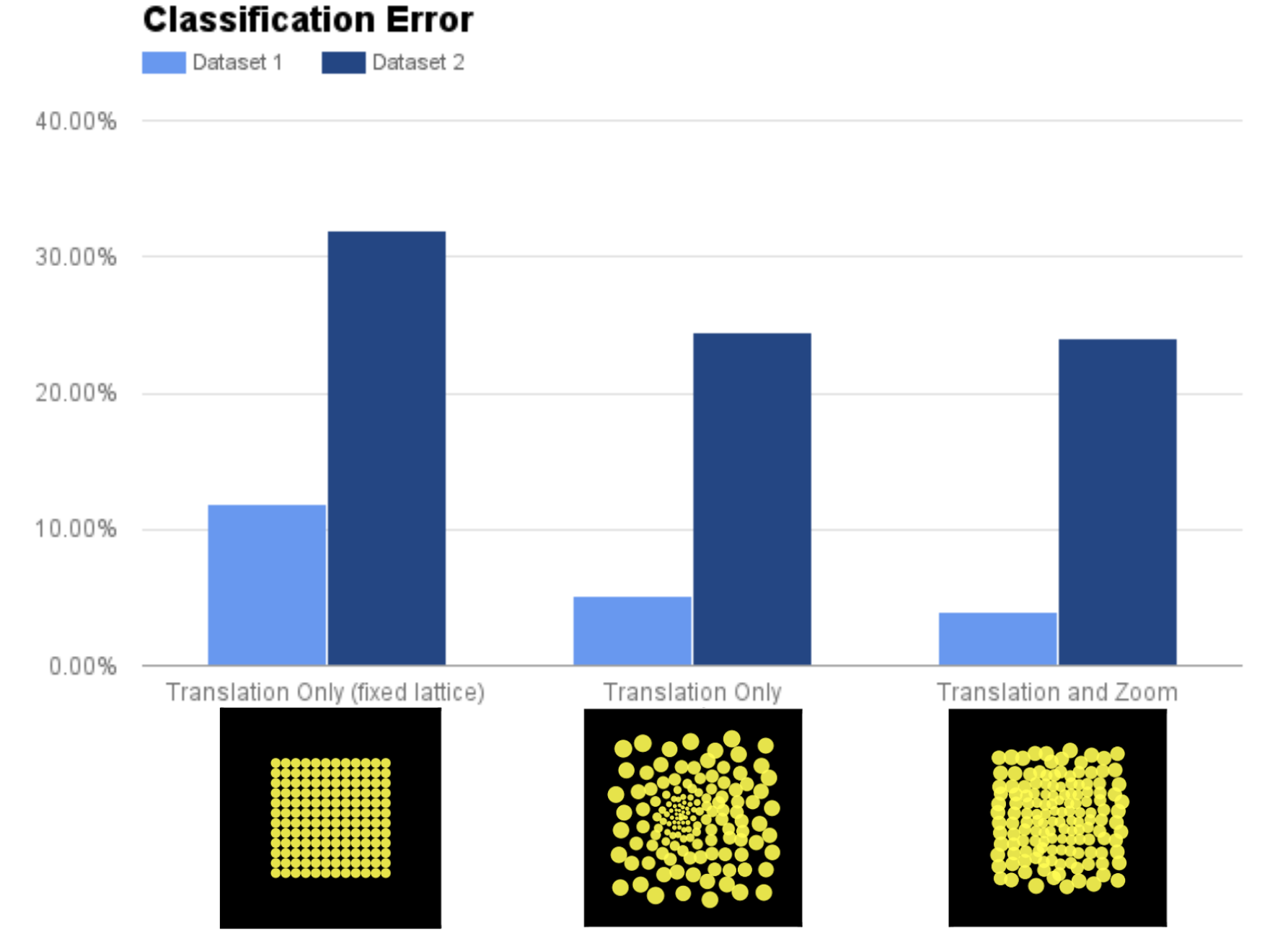

To get a better idea of the utility of our learned retinal layout, we compared the performance of a retina with a fixed (unlearnable) lattice, a learnable lattice without zoom and a learnable lattice with zoom:

Performance on two versions (Dataset 1 and Dataset 2) of the Cluttered MNIST dataset. Dataset 2 contains randomly resized MNIST digits making it more difficult than Dataset 1.

Perhaps not surprisingly, having zoom/learnable lattice significantly outperform a fixed lattice which can only translate. But what is interesting is the performance between a learnable lattice only with the ability to translate performs about as well as a model which can also zoom. This is further evidence that zooming and a foveal layout of the retinal lattice could be serving the same functional purpose.

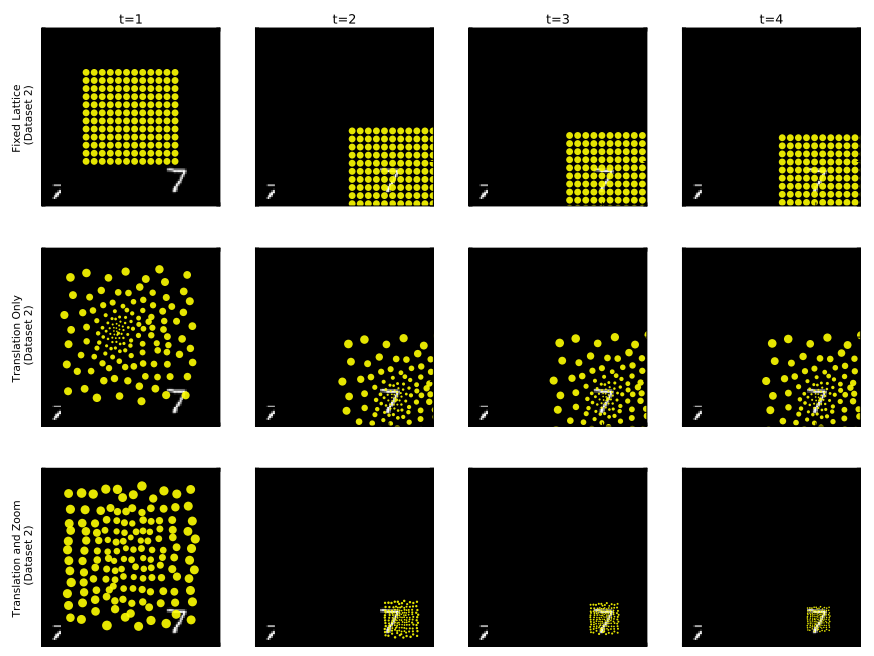

Interpretability of Attention

Earlier, we described the utility of attention in efficiently utilizing limited resources. Attention also provides insight into how the complex systems we build function internally. When our vision model attends over specific parts of an image during its processing, we get an idea of what the model deems relevant to perform a task. In our case, the model solves the recognition task by learning to place its fovea over the digit indicating its utility in classifying the digit. We also see the model in the bottom row utilizes its ability to zoom for the same purpose.

The attention movements our model takes unrolled in time. Model with fixed lattice (top), learnable lattice (center), learnable lattice with zoom ability (bottom).

Conclusion

Often we find loose inspiration from biology to motivate our machine learning models. The work by Hubel and Wiesel 1 inspired the Neocognitron model 2 which in turn inspired the Convolutional Neural Network 3 as we know it today. In this work, we go in the other direction where we try to explain a physical feature we observe in biology using the computational models developed in deep learning4. In the future, these results may lead us to think about new ways of designing the front end of active vision systems, modeled after the foveated sampling lattice of the primate retina. We hope this virtuous cycle of inspiration continues in the future.

If you want to learn more, check out our paper published in ICLR 2017:

Emergence of foveal image sampling from learning to attend in visual scenes

(https://arxiv.org/abs/1611.09430)

-

Hubel, David H., and Torsten N. Wiesel. “Receptive fields, binocular interaction and functional architecture in the cat’s visual cortex.” The Journal of physiology 160.1 (1962): 106-154. ↩

-

Fukushima, Kunihiko, and Sei Miyake. “Neocognitron: A self-organizing neural network model for a mechanism of visual pattern recognition.” Competition and cooperation in neural nets. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1982. 267-285. ↩

-

LeCun, Yann, et al. “Handwritten digit recognition with a back-propagation network.” Advances in neural information processing systems. 1990. ↩

-

Gregor, Karol, et al. “DRAW: A Recurrent Neural Network For Image Generation.” International Conference on Machine Learning. 2015. ↩